HADRIAN’S WALL: Boundary Monument for the

Northern Frontier of Roman Britannia!

John F. BROCK, Australia

John F. Brock

1)

This paper will be presented at the FIG Working Week 2017 in Helsinki,

Finland, 29 May – 2 June. Much hypotheses and over-thinking has taken place over hundreds of

years in an effort to attribute purposes for the raison d’etre of the

wall across northern Britain erected at the behest of the formidable

Roman Emperor whose name has been ultimately used to describe this

intriguing edifice. John Brock makes his own offering to the discussion

table about what served as the main reasons for the erection of such a

notable memorial to the time of the renowned civilization during the

second century.

ABSTRACT

“A man’s worth is

no greater than his ambitions.”

– Marcus Aurelius |

|

Fig. 1 A section of Hadrian’s Wall in north England showing material and

construction type

Much hypotheses and over-thinking has taken place over hundreds of

years in an effort to attribute purposes for the raison d’etre of the

wall across northern Britain erected at the behest of the formidable

Roman Emperor whose name has been ultimately used to describe this

intriguing edifice.

Was it built for defence, border control, a

demonstration of power or any number of associated intentions as a

strategic military device at the extremity of the territorial outskirts

of the Great Empire? Many postulations have been advanced by engineers,

stone masons, clerks of works, military experts, academics,

archaeologists, historians, paleontologists and all the usual suspects.

However I have only sourced one other opinion for its creation put

forward by another land surveyor like myself having been offered by my

very good friend from the US Mary Root who I see at least once a year at

the Surveyors Rendezvous held annually in different locations within the

USA to celebrate the local Surveying history of many notable places in

the Land of the Free and President Surveyors (please note that US

Presidents Washington, Jefferson and Lincoln were all land surveyors!).

Well it just so happens that I am not just a practising “historical

detective” (as I label those involved in my profession!) but I am an

active field historian with a Masters degree in Egyptology from

Macquarie University in Sydney. In addition to this area of

personal and professional interest I have done considerable research

into ancient Greek and Roman surveying together with a diversion into

the surveyors of China’s antiquity as a background to my paper “The

Great Wall of China: The World’s Greatest Boundary Monument!”

With such a cursory introduction to my own research base

I will be making my own offering to the discussion table about what

served as the main reasons for the erection of such a notable memorial

to the time of the renowned civilization during the second century.

After I elaborate further about my analysis of the wall’s design with

specific attention drawn to certain features not before grouped together

along with a focus on the desires and intentions of Emperor Hadrian

himself there may be some agreement that this iconic line across the

topography is a true boundary monument in the ancient Roman traditions

as a demarcation line of the northern limit of the Empire’s frontier in

the north western territory of its second century enforced tenure.

1. INTRODUCTION

|

“It is not what

you look at that counts; it is what you see!”

- Henry David Thoreau, Philosopher/Surveyor. |

On the five occasions that I have travelled to the United Kingdom on

only one instance have I gone by road northwards to Scotland during

which I only caught a fleeting glimpse of Hadrian’s Wall in 1998.

After nearly 19 years I will actually be staying at the town of Wall in

accommodation adjacent to this legendary symbol of Roman times within

the area such premises having been constructed with stones from the

original structure itself. My subsequent curiosity with this

ancient Roman masterpiece was propagated by initial readings of various

texts and web articles most of which I procured from the UK itself.

Most authors have proposed that the Wall had multiple purposes for its

installation dismissive of a principal motive for placement as a

defensive barrier or fortification suitable for the Roman forces from

which to mount an armed resistance. Through my interpretations of

the various features of the Wall’s design combined with an instinctive

feeling for the mood of the Roman Ruler himself I will mount a

convincing proposition that the main purpose of Hadrian’s Wall was as a

boundary monument placed to delineate the dividing territorial line for

the northern limit of Roman Britannia at the same time serving notice to

any would-be interlopers that any transgressions past that line would

bring great trauma.

May I emphasise that my research is not totally exhaustive but I

have obtained many excellent publications issued over many hundreds of

years which have provided me with a quite broad understanding of how

many surveyors were employed by the great Empire to maintain and

supervise all matters pertaining to matters of civic jurisdiction and

orderly inhabitation of the lands over which claims had been

established. Roman Surveying Law and Doctrines were well versed

and enforced by a Surveying Profession which bore great esteem and

respect along with a dependency on such experts to solve boundary

disputes and facilitate the creation and operation of new towns, roads

and aqueducts considered vital for the convenience and livelihood of its

citizens and vast military regiments.

2. JULIUS CAESAR INVADES BRITANNIA

“Veni, vidi, vici”

(“I came, I saw, I conquered.”)

– Julius Caesar (47 BC)

|

The first incursions by Rome across the sea into

Britannia were made by Julius Caesar in 55 and 53 BC with continuing

intensity over the years under the reigns of subsequent emperors

Augustus, Tiberius and Caligula. It would not be until almost another

hundred years before the Romans finally conquered Britain in 43 AD when

Claudius dispatched four legions to finalise the job and even from then

on there was still formidable opposition to keep the usurping legions

south of what is considered Caledonia (visa vie later most of

Scotland). There was the perception that there was little wealth or

suitably arable lands upon which income could be generated added to the

tenacity of the battle hardened highlanders whose fight to the death

toughness would make many a seasoned soldier reluctant to take them on

in their own surroundings. These eras of Rome’s expansionary ambitions

are not the basis for this paper but they do serve as a salutary source

as to what drove Hadrian to bring about the laying of what has become a

renowned landmark of the Roman Empire at its mightiest during the second

to the fourth centuries after Christ. What has been labelled “the Fall”

of the Roman Empire was already well into its death rolls by the time

the Romans ultimately evacuated their Britannic stronghold in 411 during

the rule of Emperor Jovinus and his Consul Honorius et Theodosio.

3. HADRIAN BECOMES ROME’S EMPEROR

|

“Better than a thousand hollow words is one word that brings

peace”- Buddha |

If the word “wall” was inserted where “word” is in this

quote it may go some way to explain Hadrian’s strategy to put up his

wall in northern Britannia when he toured his western colony in 122.

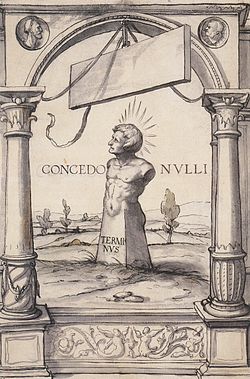

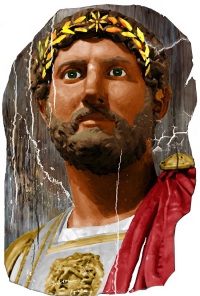

Fig. 2 Roman Emperor Hadrian

In 117 AD Rome’s second “friendly” regent Trajan passed

away leaving control of Rome’s extensive holdings to his successor

Hadrian who was 41 (born Publius Aelius Hadrianus in 76 possibly in

Itallica which is now part of Spain – but it has been suggested that in

fact he was born in Rome itself?) when taking over control. Rebadging

himself as Caesar Traianus Hadrianus Augustus the new ruler clearly

portrayed his traditionalist attitude with a distinct bias towards the

classical culture of the ancient Greeks along with archaic literature

and writings of folklore as well as displaying his veneration for his

First Emperor Augustus through the inclusion of his name in that which

he had adopted. One writer says that he was a “dedicated devotee of

Octavian-Augustus, and had a bust of Octavian in his bedroom.” I am

sure that his wife was delighted! Shelving the expansionist policies of

some of his predecessors which had stretched the capacity of the

governing regime to maintain control and order at the extreme edges of

those regions far removed from the Rome-based Senate responsible for its

existence Hadrian saw the need for more passive measures to be

employed. The new ruler embarked on a program to consolidate the

current holdings of the dominion in order to minimize the exposure of

invasions and raids against the thinly spread legions guarding the

vulnerable outer limits of the Empire’s furthest perimeters. Hadrian

had a resolute character as well as having been remembered as a leader

with moderation along with Nerva (96-98), Trajan (98-117) and his

successors Antoninus Pius (138-161) and Marcus Aurelius (161-180)

collectively referred to as “The Five Good Emperors.” In a paradox of

his personality his moderation in areas of governance were matched by

his extravagance in public works such as the enlargement of The Pantheon

and of course the placement of the Britannic Wall. The concept of

territorial limits had more to do with the identification of lands

currently under Roman control and those destined to be, rather than a

declaration that the lines identified would remain at the outermost

edges of the Empire. There was also a paranoic perception, sometimes

justified, that the far removed generals at a tyranny of distance would

be driven to forge alliances with those nearby chieftains outside the

designated lines and sever ties with the Empire. Emperor Domitian

(81-96) introduced frontier works in Germany with timber towers linking

forts while Trajan had added fortlets just prior to Hadrian erecting a

timber palisade in this colony (PH p.15). Where naturally occurring

major landscape features such as rivers, cliffs or water table crest

lines existed they were charted as the boundary of the Empire lands for

the outside regions.

In legalistic parlance rightful ownership of property is

demonstrated by what are referred to as “Acts of Dominion” such as

maintaining an estate in good order, paying the required Council rates

and land taxes (if applicable), plus various other actions but with one

very specific action being tantamount to secure a right of ownership

which is the construction of a dividing barrier between one claimant and

his neighbour usually being a fence or wall along the property line of

subdivision. Hence Hadrian saw an urgent need to clearly demarcate

where he believed his line of dominion had reached along the northern

frontier of his western colony of Britannia. Done without mutual

consent clearly the non consentual parties could only regard the

placement of this Wall as an act of aggression or at the very least a

provokatory signal to future confrontations by the angry rebels.

Through his extensive tour de force inspecting his absolute realm to

its entirety Hadrian formulated a capital works program to clearly

designate the limits of his power through the placement of artificial

lines of demarcation where no natural geography presented itself to

adopt as suitable frontier perimeters known as “limes” which were those

external boundaries as compared with “limites” being dividing lines

between provinces within the overall total regime. During his

visit of 122 AD to Britannia he oversaw the erection of the great

construction dividing wall 80 Roman miles (a Roman mile was 5,000 Roman

feet being equivalent to 4,854 Imperial feet – a pace was equal to 5

Roman feet) from Wallsend-on-Tyne to Bowness-on-Solway along the

northern territorial rim of his western colony (a distance of about 120

kms).

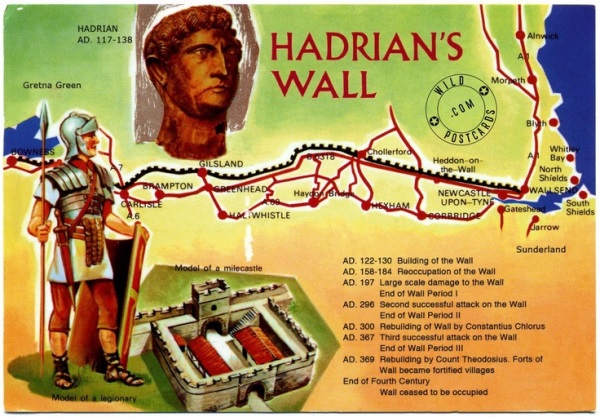

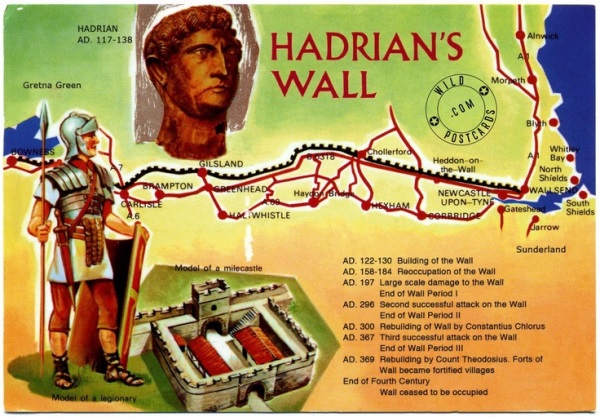

Fig. 3 A postcard showing Emperor Hadrian’s bust looking over

his impressive wall

The new leader was determined to enforce “peace through

strength” thus devoting his efforts to erect clear symbols of might

enclosing all that was his. In so doing he was giving defiant notice to

any tribes outside those fortifications who contemplated crossing these

barriers with ill intent they most certainly would attract the full

retribution of the Roman legions in response. Clearly the Wall was

solidly and substantially built but with the relatively sparse

positioning of fortlets (with gates) between quite extended stretches of

narrow stone walls it was far from impregnable. The gates placed were

to allow passage to and from the adjoining lands with a tacit intent of

frontier control for selective admissions and exclusions as decreed.

For many years after the refocus directed towards the royal edifice

since the 17th century “rediscovery” of the Wall there was much dispute

about who actually issued the decree to bring about its construction but

subsequently two powerful items have emerged to prove conclusively that

its paternity belongs to Hadrian himself. Hadrian’s alleged biographer

Aelius Spartianus from the Scriptores Historiae Augustae (translated as

Augustan History) estimated to have been compiled some time between AD

285 and 335 declares in Hadrian XI, 2-6: “And so, having reformed the

army quite in the manner of a monarch, he set out for Britain, in 122.

There he corrected many abuses and was the first to construct a wall,

eighty miles in length, which was to separate the barbarians from the

Romans.” Then as though the ancient emperor was watching over the

modern proceedings and discussions concerning the archaeological

investigations and restorations of his paean glorious in 1715 at Hotbank

Milecastle No. 38 an inscribed slab of stone (now held in the Museum of

Antiquities, Newcastle) was discovered dated to the time of Britannic

Governor Nepos from 122-126 AD which in Latin states: “Imp(eratoris)

Caes(aris) Traiani / Hadriani Aug(usti) / A(ulo) Platorio Nepote

leg(ato) pr(o) pr(aetore)”, translated into English saying: “Of the

emperor Caesar Traianus Hadrianus Augustus, the legion II Augusta (built

this), while Aulus Platorius Nepos was legate with powers of a praetor.”

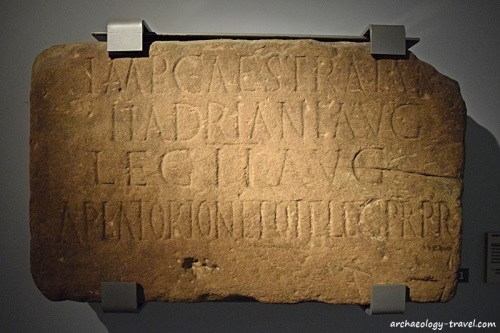

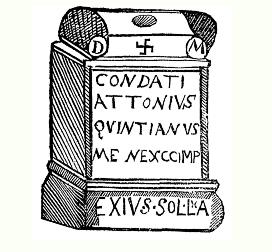

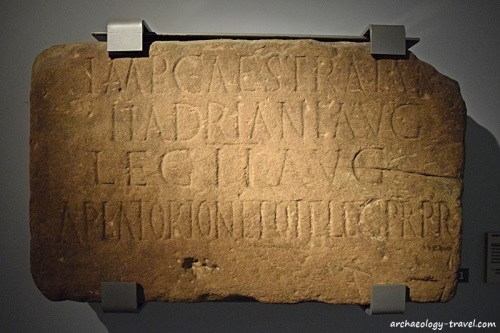

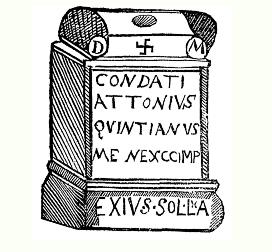

Fig. 4 Stone inscribed c. 122-124 to

verify that Hadrian’s Wall had been authorised by the

Emperor personally around 122 that section having been built by Legion

II Augusta

Indeed another monumental artefact bore witness to the

approximate completion date of the Wall around 136 adding testimony to

one of the other total of three legions which carried out the massive

project found near the east gate of Moresby fort translated to read:

“(This work) of the Emperor Caesar Trajan Hadrian Augustus, father of

his country, the XX Legion Valeria Victrix (built).” (stone dated

128-138). Fig. 5 A section of the Great Wall of China showing some

fortlets. Another parallel for a stone wall erected as a solid symbol of

ownership to those outside hordes are the early stages of China’s Great

Wall initiated by the first Emperor some time around 200 BC. The wall’s

height and breadth could not prevent them crossing it but any such

breach of the stone ramparts was a sure passport to big trouble for

those warlike groups not remaining on their side of it. The more well

known Great Wall of China with high walls lined with castellations along

wide interconnecting fortifications was modified and amplified to this

impressive megastructure during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) but this

battle-ready bastion saw very little wartime activity during the tenure

of this legendary ruling clan famous for their ornate blue pottery.

4. THE APPARENT ENIGMA OF THE VALLUM – ITS REAL FUNCTION

|

“Once we accept our limits, we go beyond

them” – Albert Einstein |

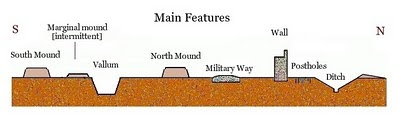

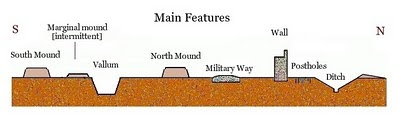

Fig. 6 Cross sectional diagram of the

Wall construction

Many writers have dismissed the inclusion of the Vallum as

inexplicable in its function. The Vallum is a trench dug inside the

south side of the Wall with earth mounds lining the top edges on both

sides running for its entire length apart from where natural features

like rocky outcrops or river banks interrupt its progress. One

author states that it has been surveyed like a road but is unlikely to

have been used for this reason while another pronounces it may have been

included as an additional defensive mechanism as an obstruction to

invading armies. At its depth and location in addition to the many

lengths of narrow wall too thin from which to wage even defence by a

single line of archers let alone catapults or pots of boiling oil it

would appear less probable that the Vallum was placed to serve any

credible second line of resistance after this first ineffective barrier

had been breached by any sizeable swarms of invading marauders.

If I may digress now to a much earlier archaic period in

pre-Roman history in support of my suggestion that the Vallum in fact

formed part of the traditional techniques of construction adopted for

the creation of boundaries first attributed to Aeneas who is said by

mythology to be the direct ancestor of Romulus and Remus, the mythical

wolf-suckling twins who founded Rome. As an illustration of the

extent to which the Romans incorporated the establishment of new towns

into their folkloric sagas the writer Virgil describes how Aeneas

founded a city in Sicily:

“Meanwhile Aeneas marks the city out

By ploughing; then he draws the homes by lot”

All Roman Surveyors were aware through their training of

the old custom whereby the limits of a new town were marked out by the

consul by ploughing a furrow around it. Another author Ovid, a studier

of the law including that pertaining to surveying, said that the

dividing up of land with balks (limites) by a “careful measurer” (cautus

mensor) emphasised the importance attached to the art of surveying.

The line drawn around a town was referred to by Virgil

as sulcus primigenius (“the original furrow”) and was monumented with

boundary stones according to Tacitus and Plutarch. Actual boundary

stones have been discovered at Capua placed during the Second

Triumvirate bearing inscriptions “By order of Caesar (Octavian), on the

line ploughed”. When the Emperor wanted to extend the limits of Rome he

maintained the traditional inclusion of the “original furrow” placing

inscriptional carved boundary stones which are still present today in

evidence to his realignment of the boundaries of the eternal city.

Fig. 7 Caesar Augustus coin (29-27 BC)

with the ploughing of Rome’s first boundary furrow

Revered first Emperor Caesar Augustus so much cherished

the ancient folklore of Rome that he had a Denarius coin struck dated c.

29-27 BC with his bust on the obverse and the ploughing of Rome’s first

boundary furrow on the reverse during his reign for the citizens to bear

recognition of their hallowed traditions. Emulating his legendary idol

Caesar Augustus Hadrian was not going to miss a chance to present

himself in a similar portrayal of himself as the City Founder ploughing

the new boundaries with a team of oxen on a coin from Aelia Capitolina

(Jerusalem) in about 131-136 AD in a very clear demonstration of his

admiration for his predecessor together with the folkloric divine

creation of a limes in the form of a Vallum or Pomerium.

Fig. 8 Hadrian coin (c.131-136 AD) with

the symbolic ploughing of a new first boundary furrow

Indeed the folklore of the birth of Rome itself said to

be in 753 BC has Romulus and Remus as direct descendants of the Trojan

Prince Aeneas founding the new city. One version of the myth has

Romulus cutting a sulcus primigenius (first furrow) around the perimeter

of where he decreed the city limits to be incorporating the Palatine and

Capitoline Hills just as his ancestor Aeneas had done in other towns

before him in what is believed to be an Etruscan ritual which was

inclusive of the proposed line undergoing selection and final placement

by auguries exercising divine control. In this recital of the folkloric

epic when Remus ridicules this action by his brother by jumping back and

forth over the sacred furrow Romulus kills him in what must be regarded

as an extreme act in border control indeed. Subsequently a

substantial wall was erected outside this trench with the area between

the inside of the wall up to and including the ditch being termed “The

Pomerium” within which building construction was forbidden together with

other bans prohibiting various legal actions otherwise enforceable

within the inner property zone by the duly empowered judicial

appointees. Entry from outside this line of strong delineation

could take place only with permission granted by those authorities

entrusted with the protection of the livelihoods of the citizens of

Rome. In fact the dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla expanded the limits

of the City of Rome in 80 BC in an act of absolute power with his new

town limits further marked out by white marker stones called cippi which

were commissioned by Claudius to delineate his extension of The Pomerium

some of which survey monuments are still in situ today as recorded by

Tacitus and outlined by Aulus Gellius.

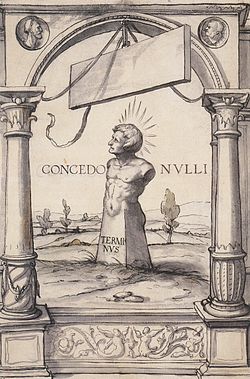

The Romans even had a god called Terminus - God of the Boundary

Stones closely affiliated with the principal deity Jupiter. Indeed

it is the Romans who introduced the Feast of Terminalia which is an

annual ceremony with pomp, pageantry and identification of the boundary

stone monuments designating the area within which protection is

guaranteed and order maintained. Boundary stones took many

different forms with particular types of monuments being set to indicate

the nature of the tenure under which the enclosed properties were held.

Another absolutely

splendid effort in scholarly publishing is Brian Campbell’s

handsome volume on “The Writings of the Roman Land Surveyors”

(in Latin Corpus Agrimensorum Romanum) which most astutely

translates the Latin texts of the Roman authors who compiled a

veritable instructional handbook on how surveying was to be

conducted within the Roman Empire. May I say that this work is

extraordinary and has given me a detailed appreciation for the

technical and judicial expertise which was vested in the

Surveyors privileged to undertake such activities for the

administratively thorough control imposed upon its charges.

I need to clarify the interpretation of the word Vallum as

literally it means a “mound of earth” but in the context of

Hadrian’s Wall it more specifically describes the trench

following the line of the limes or boundary line which has

mounds of earth along its top edges just as the sulcus

primigenius (“first furrow”) had placed along its upper edges

formed from the earth excavated from the trench itself. |

Fig. 9 Terminus as a boundary stone |

To

my amazement and delight on page 273 of Brian’s superb book he deciphers

the original Latin text in the Section “…Discussion About Lands” to say:

“Villa comes from vallum, that is, a heap of earth, which is normally

established in front of a limes” which is actually the borderline of the

outside extremity of a Roman frontier dividing it from international

lands held by neighbouring nations or peoples. Furthermore on page

263 under the title: “Here Begins a Discussion of Boundary Markers Set

Up in Various Provinces” is stated:

“I have established a small ditch, which was dug out, on

a boundary as a marker.

Bigger ditches you will also certainly find as boundary markers.

You will undoubtedly discover a raised limes, that is, a balk.

I have built walls from limestone to mark boundaries.

I have established banks that have been dug out to mark boundaries.

You will find piles of earth marking boundaries.”

These incredible discoveries add firm weight that the

Vallum incorporated within the design specifications for Hadrian’s Wall

was following those strict instructions laid down in the Roman Surveyors

Instruction Manual for the presentation of an International Border Line.

This invaluable nexus to the times of the Roman surveyors translates a

voluminous corpus of texts providing all historians but more especially

surveyors with a detailed overview of what types of boundary marking

were carried out, classifications of land types, as well as all manner

of natural feature which could be adopted as boundary lines where

suitable. There are even descriptions and diagrams of what style

boundary markers and boundary stones were to take in given

circumstances. For any interested Surveyor historian this

publication is a must-have and I would recommend the supplier “Book

Depository” on the internet who have the best price together with free

delivery anywhere in the world!

In an historical essay in what has been termed by its

composer as “the puzzle of the Vallum” this scholar went one giant step

towards explaining “the inexplicable!” Published in a 1921 issue of a

journal called “The Vasculum” R.G. Collingwood titled his work: “The

Purpose of the Roman Wall” in which he says: “… the continuous line was

at first designed to serve simply as a mark to show where the Roman

territory ended.” Precisely Mr. C as any suggestion that the Vallum was

a defensive earthwork is itself indefensible. For rampaging bands of

villains it was merely a ditch with a speed hump. He goes on to

reiterate: “The puzzle of the Vallum simply disappears when it is

suggested that it was not a defensive work but a frontier-mark, a line

indelibly impressed upon the earth to show the wandering native where he

might not go without accounting for his movements.” Could not have said

it better myself!

Well I am now going to propose a more definitve reason

and origin for the placement of the Vallum combined with its true

purpose. It surprises me that none of these astute writers who are

perplexed by the Vallum have not seized upon the very first indicator of

why this structure was an essential element of this territorial border

line – the Roman names first applied to it were the Vallum Hadriani or

the Vallum Aeliani or Aelium (Hadrian’s family name was Aelius).

With strict adherence to the instructions issued to the Roman land

surveyors to delineate a limes (international line of demarcation) it

was an explicit directive to make a Vallum (literally “earth mound”).

Naturally to form the earth mound required to construct this visible

line of subdivision the quickest way available the legionary project

supervisors devised the earthwork technique of digging the required

quantity of material from the ground leaving a trench alongside then

stacking the spoil solidly along the edge of this continuous excavation.

Hence once again illustrating the interpretation of the meaning of a

Vallum evolved to include the trench AND the mound in its description.

With the benefit of the aforementioned facts to

corroborate my following pronouncement may I propose that the Vallum was

the first inclusion in the design for the limes (boundary line) to

demarcate the northern limit of Rome’s Empire with the famous Wall an

additional barrier added to provide a show of power. The western

part of this limes was initially placed consisting of a Vallum only

until the stone creation was extended sometime later to complete the

imagery of dominance. Thus the creation of the Vallum was the

first step in the establishment of this northern borderline once again

with the more sturdy stone divider being set at some time well after the

first delineator had been laid down.

5. WALL DESIGN AND CHARACTERISTICS

“Make the

workmanship surpass the materials.”

- Ovid (43 BC-17 AD) |

|

A burning question which has divided all scholars on the

planning, design and project management of this major construction in

the Roman capital works program has been just how much direct personal

association the Emperor Hadrian himself had in its detail and execution.

Well another author with whom I forthrightly concur is Paul Frodsham who

mounts a compelling argument in his book: “Hadrian and His Wall” that

the architecturally inclined Ruler not only had input into the

pre-planning of the Wall’s design but also personally directed some

aspects of the building work while on his site inspection during the

Britannic leg of his Royal Tour. With such a notion in mind it is

not hard for me to further incorporate Hadrian’s penchant for history

and tradition as alluded to previously in hypothesizing that the Vallum

was added during the erection of the Wall at its earliest incarnation to

create the true legendary image of a boundary line as had been initiated

by Aeneas, Romulus and a host of his predecessors in very much a

recreation of The Pomerium originally enclosing the Eternal City of Rome

itself. Such a final masterpiece with historic overtures would

most certainly have pleased the man mostly honoured with the exceptional

monument bearing his name for posterity to admire and marvel upon.

Within the wall were incorporated what have been called

milecastles due to their occurrence at every Roman mile thus totalling

80 with two turrets in between each of these structures to provide look

out posts at each intervening 1/3 Roman mile thus adding up to be about

160 thereto. Apart from offering a view to the north to detect

foreign troop movements all of the manned stations looked more clearly

towards the south to allow for a continuous ability to forewarn

regiments of soldiers camped within the forts and villages of impending

assault.

As has been irrefutably established by many more learned

of the Wall than I for a considerable percentage of its length it was

not a fortified bastion or even bore formidable dimensions to singularly

deflect any major incursions. The size of the Wall varied from a

nominal height of 10 feet (3 metres) with an equivalent width up to 20

feet (6 metres) high also with a matching girth so for much of its

coverage the sections with the lesser height presented no significant

restriction to those warring groups who wished to create conflict on

their foreign oppressors.

Fig. 10 Photo of the US/Canada borderline which is the

unfenced trench at Blaine in Washington state |

A modern example of a trench being

placed to demonstrate the division between two countries can be

found even today on the US/Canadian borderline at the north

western US town of Blaine within the which my very good friends

Denny and Delores Demeyer reside. Even though the depth and

width of this sunken barrier does not preclude access there will

always be a very interested US Border Patrolman staking out his

continuous vigil on the southern side of the border keeping a

very concerned eye over anyone making an unauthorized or

uninvited crossing of this line of division with a similar

intent as those Roman sentries who manned the turrets along the

lengths of Hadrian’s Wall. |

6. SURVEYING AND BUILDING THE WALL

|

“Every wall is a door”

– Ralph Waldo Emerson. |

I am quite sure that Hadrian had no desire to make his Wall anything

like a door to encourage hostile northern tribes to cross into the Roman

domain but the deterrent qualities of his Wall were not so physical

rather than more indicative for in some ways his Wall was very passable

not representing a true decisive barrier to opposing camps. Three

legions were assigned the duty of erecting this symbol of territorial

division II Augustus, VI Victrix and XX Valeria Victrix but upon its

completion it was manned by auxiliaries rather the legions themselves

which were called to other pressing duties somewhere removed within the

extensive perimeter of the Roman Empire. There is some

inscriptional evidence for a detachment of the British Fleet making some

of the granaries at the forts.

All materials used upon the Wall construction were

quarried locally thus giving the final product a variety of finish only

possible through the utilisation of natural resources sourced from the

surrounding geological deposits with their distinctive evolutionary

origins and nearby timber where such wooden carpentry was included or

necessary.

Through a very excellent and thoroughly researched

publication by Peter Hill titled: “The Construction of Hadrian’s Wall”,

Peter has estimated just how many legionary surveyors were available to

carry out the task of surveying the long straight sections of the wall

construction as well as the likely work schedule providing a likely time

for completion of the survey work required. For the reconnaissance and

surveying required to facilitate the site selection and final

positioning of the Wall I have formulated the Survey Work Statement for

the activities necessary for a project of this proportion. Departing

from any possible ritual selection of the Wall’s location by the Consul

or auguries the ultimate function of this divisional barrier was to

signify the limit of territorial governance while also setting an

adequate line of sight both northerly and southerly for the sentries on

watch to detect any likely trouble which may have been brewing along

with the dual capacity to sound the alert of any likely attack.

Later I am going to inform you of how many surveyors

were available to each Roman legion as indicative of just how much

manpower was devoted to the vital capacity of carrying out the survey

requirements for the Roman nation throughout its widely distributed

colonies.

The first duty was to survey and fix the exact line of the Wall such

location governed by the preceding parameters of sight lines and

prevailing topography taking into account interceding natural features

which themselves could serve as obstructions to foreign access such as

cliffs, riverbanks and whinsills. Due to the extensive period of

time during which the nearby land had already been under occupation it

is quite likely that the preliminary scouting party had a fairly

definitive idea of where the Wall would be best placed with the crags of

the whinsills dividing the future work into western and eastern sectors

punctuated by this extant natural barrier building westerly towards the

Solway Firth and in the opposite direction to the Tyne River.

During this reconnaissance the surveyors would have left small rock

cairns possibly with a small line of stones in the direction towards the

next visible marker or landmark as well as stakes between which the

later construction survey parties could align straight sections of wall

and make realignments for angles where necessary. As these

probably wooden stakes may not have been painted another contemporary

author on the Roman surveyors observed these men placing stakes with

flags on them for easier sighting against a camouflaging background of

similarly textured vegetation. The ultimate route chosen ran

between the banks of the River Tyne near Wallsend on the eastern

seaboard and the shores of Solway Firth at the western end. Peter

Hill estimates that there were about 10 mensores (surveyors) present in

each legion forming part of a group known as the immunes as with their

fellow professional compatriots such as architects, engineers, builders

et al as they were immuned from carrying out other military work due to

the requirements of their designated speciality. The surveyors

were called mensori (singular mensore) with a team of them referred to

as a metatore. This meant that there was a surveying pool of

around 30 surveyors to lay out the straight lines where they could fit

the landscape as well indicating the spots for the erections of

milecastles (every Roman mile) with two intermediate turrets (or look

out towers) at around 1/3 mile separation in addition to selecting sites

for troop encampments for the total workforce.

Without reiterating the specifics of Peter’s

calculations if I may I will summarise the final approximations of the

various sections into which the legionary surveyors may have split their

overall task. In Wall miles the likely sections surveyed were Wallsend

to Ouseburn 3 miles; Ouseburn to Dere Street 18 miles; Dere Street to

North Tyne 5 miles; North Tyne to the eastern end of Whin Sill (MC34) 7

miles; Whin Sill 13 miles; Western end of Whin Sill (say MC46) to

Irthing 3 miles; Irthing to the Eden 17 miles; Eden to Bowness 14 miles.

Peter’s predicted time to complete the initial survey, setting out the

milecastles and turrets most probably from one end together with

straight alignments and angles when required could have done in about a

month. Subsequent construction of the Wall itself is believed to

have taken at least fourteen (14) years with some later modifications

being added after this time where such additions were regarded

necessary. Thus the anticipated completion date for the Wall came

only two years before Hadrian’s passing which meant that he never got to

finally witness his testimonial before his death.

7. HOW LONG DID HADRIAN’S WALL LAST?

|

“The reward of a thing well done is

having done it.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson |

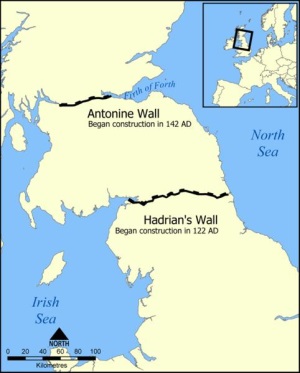

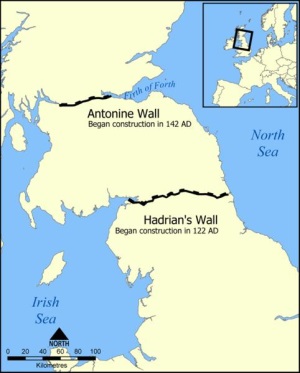

Between 139 and 140 (or

some say 142) Hadrian’s successor Antoninus Pius had what is now

known as The Antonine Wall built of earth and timber

substantially further north at about 140 miles (224 kms) by road

than the Wall we are more concerned with connecting a shorter

overall distance of 37 miles (59 km) from the Firth of Forth to

the Firth of Clyde.

Once again the antiquarian Roman name given for this newly

positioned limes was the Vallum Antonini and this new

construction conformed rigidly to the written regulation to make

it a Vallum with the compacted earth mound along the rim of the

dug out channel. This earth wall standing at approximately 10

feet (3m) tall with an average width of 16 feet (5m) so making

this structure an even less imposing deterrent to possible

invasion than Hadrian’s Wall did. As monitoring and observation

of foreign troop movements was vital watch towers and fortlets

made of timber were inserted along this shorter territorial

limit around 100 miles (160 kms) directly north of its more

impressive southern counterpart. |

Fig. 11 Map showing the location of Hadrian’s Wall and the later

Antonine Wall |

Even though it had been further

strengthened with the insertion of more forts along its length the order

to abandon this later less substantial barrier was given in 163 with a

troop withdrawal back to the more substantial wall. With reasons

unclear there are some who attribute this retreat to an uprising by the

Brigantes with 15 years of revolts ensuing with other tribes joining the

feisty Caledonians. Periods of rebuilding Hadrian’s Wall due to

damage incurred during this ongoing resistance served to reinforce the

importance of this northern bastion in Rome’s colonies along with

providing it with greater longevity which allows us to enjoy and study

it in the 21st Century. Along with a letter sent in 410 from Roman

Emperor Honorius to the Roman Britannic forces “to look to their own

defences” against the accelerating hostility from the Saxons, Scots,

Picts and Angles came a refusal by Rome to send any reinforcements thus

sounding the death knell for Roman Britain. However Hadrian’s Wall

had represented the symbol of the northern frontier of the Roman Empire

in the West for nearly 300 years being now a celebrated treasure for

archaeologists, historians and land surveyors to swoon and walk over

instead of the hordes of angry tribesmen intent on vengeance during its

time as a boundary divider.

8. SURVEYORS – ROME’S ULTIMATE LAND EXPERTS!

| “Waste no more time

arguing what a good man should be. Be one!” – Marcus Aurelius

|

|

We know that surveyors were on the list of immunes

because a list of specialists for the legions was compiled in the sixth

century in a law code copied from an earlier (list) put together by a

man known under many similar aliases as Taruttiensus Paternus,

Tarruntiensis or Tarrutenius who was possibly the same individual

mentioned by writer Dio as ab epistulis Latinis (secretary for Latin

correspondence) to Marcus Aurelius then acting as independent military

commander in 179 AD. The military manual written by this man was titled

De Re Militare or Militiarium listing the tasks to be carried out by

stone cutters, carpenters, glass workers, plumbers, cartwrights,

blacksmiths, coppersmiths, lime-burners and charcoal-burners, surveyors

and ditchers as well as several clerical immunes keeping legionary

records of strength, enlistments, discharges, transfers, expenses and

pay records. Architecti were also included as most essential with two

known to be Amandus at Birrens and Aelius Verines at Mainz.

Fig. 12 Stone altar of Attonius Quintianus |

A most exciting discovery was a record of the discovery of

stone altar in 1709 at a place called Coniscliffe which I can

gather is near Piercebridge which unfortunately is now lost.

From the adjacent sketch the inscription is interpreted to say:

D(eo) M(aris)

Condati

Attonius

Quintianus

Men(sor) evoc(atus) imp(erratum)

Exins(su) sol(vit) l(ibens) a(nime) |

This inscription translates to be: “To the god Mars

Condates, Attonius Quintianus, Surveyor Evocatus, gladly fulfilled the

command by order.” What a brilliant find decoded by Gales, Thoresby and

Horsley said to be placed between 43 and 410 AD so most probably during

the time frame associated with Hadrian’s Wall but more thrillingly it

was funded by a Surveyor who is purported to be at the time a Mensor

Evocatus which is a military specialist having completed in excess of 16

years service purported to be receiving a most impressive salary of

200,000 sesterces per annum and may even have attained the rank of chief

centurion or praefect which is of great eminence within the realms of

the Roman legions. To understand the value of the Roman currency at the

time that this surveyor lived please see Appendix C at the end of this

paper. However I will quantify our man’s salary through comparison with

other amounts paid to differing levels of officials and legionaries.

From the time of Domitian (81-96 AD) a legionary was paid 1,200

sesterces per annum, a Centurion 20,000, a Chief Centurion 100,000, a

Procurator 60,000-100,000 while a Senior Proconsul, the Prefect of Egypt

and a senior Legate were on a hefty 400,000 pa. A small farm was valued

around 100,000 while an upmarket seaside villa in Italy or large estate

in the same country would set you back 3 million sestarces. Thus our

man Attonius was doing very very well indeed so it is not unexpected

that another erudite Roman official would portray the land surveyor in

the image of some sort of wizard or great mediator in his illustrious

5th century dissertation. It is heartening to note that a Councillor in

some Italian towns was paid 100,000 per annum being half of what our

surveyor Attonius was believed to be worth!

Without having to explain to other surveyors the essential and

indispensable work done by all of our illustrious colleagues it is time

for me to once again cite the description of a Roman official from a

time late in the civilisation’s existence even after the crushing

defeats at the hands of at a time when it would be contemplated that all

authority had been usurped from those legionary surveyors which were

part of an elite squad of professionals known as “the immunes.”

Enriching the status already attained by the land surveyors of Rome

during the mightiest eras of this imperious Empire it is not surprising

that erudite and astute Roman officials such as Cassiodorus when

referring to the agrimensore (land surveyor) could proclaim:

“He walks not as other men walk !”

| To see the entire quotation of this

very wise and astute man please look up my previous paper “Four

Surveyors of Caesar: Mapping the World” to understand a full

appreciation for just how well regarded the Roman surveyors were

combined with the awe with which their activities were held in

Roman society. |

|

CONCLUSION

Hence to summarise my analysis of Hadrian’s Wall may I

please pronounce that the Wall had a principal function as a boundary

demarcation monument which designated the limit of the territory for

which Rome claimed jurisdiction and control over while being built with

symbolic recognition for the traditional formation adopted by the mighty

Empire for the limits of its cities and lands from the very first sulcus

primigenius marked out by the Founder of Rome which included such a

first furrow or trench adjoining the earthen mound known as the Vallum

which was the actual boundary of the limes or International Boundary

Line for the Roman Colony of Britannia.

For such a idyllic model of Roman greatness in engineering and

surveying to be so widely recognised by anyone anywhere in the world

truly links our profession with another legendary landmark which serves

as testimony to all who hear about or study this ancient edifice to the

skills that surveyors have demonstrated from the earliest times of

history even before such feats were recorded by the first historians.

|

|

|

Fig. 12 Hadrian’s mausoleum in Rome at the |

Fig. 13 Hadrian the Great Emperor |

It makes me proud and truly grateful to see a nation

like Finland whose surveyors have been forthright in claiming their

rightful status within the community and with whom it is a delightful

privilege and distinction to share this memorable FIG Working Week at

Helsinki in 2017 amongst men and women of dignity and achievement of all

ages from all corners of the globe (even though the globe is an oblate

spheroid?).

DEDICATION AND APPRECIATION

May I take this opportunity to dedicate this paper and presentation

to my very best friend in the World of Surveying History Jan De Graeve,

Chairman of our FIG International Institution for the History of

Surveying and Measurement from Brussels in Belgium for his dedicated and

tireless devotion to preserving and highlighting the marvels of the

History of Surveying across the entire planet demonstrative of his

passionate love of our most colourful Profession. Jan’s

encouragement and support to me over the many years during which we have

known each other since the wonderful XX FIG Congress in Melbourne in

1994 have always driven me to go further than circumstances would permit

and my obsessive love of Surveying History is matched only by my love

for him.

APPENDIX A

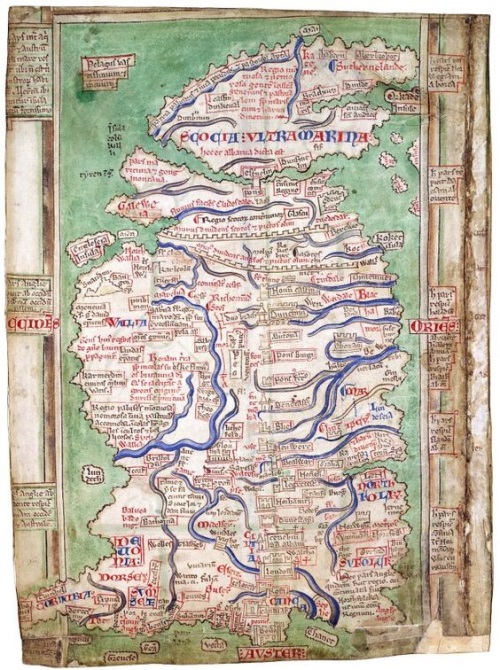

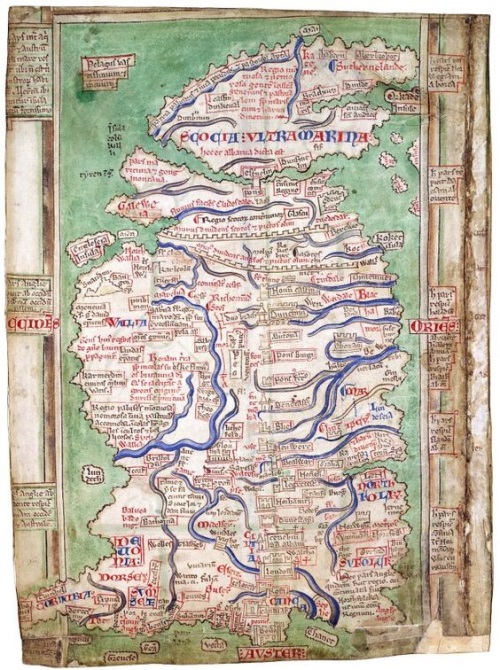

Reproduction of a 1250’s Map of Britain by Matthew Paris (who was a

monk at St. Alban’s Abbey) showing both Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine

Wall despite being depicted incorrectly in a geographical perspective.

APPENDIX B

Table of Roman Standards of Distance Measurement

| 1 Roman inch = uncia = 0.97 Imp. inch = 24.6 mm |

| 1 Roman foot = pes = 0.97 Imp. foot = 0.296 metre |

| 1 pace (passus) = 5 Roman feet = 4.854 Imp. feet = 1.48 metres

|

| 1/8 Roman mile = 125 paces = a stadium = 625 Roman feet = 607 Imp. ft

(185m) |

| 1 Roman mile = 1000 paces = a miliarium = 5000 Roman feet = 4854 Imp.

feet = 1479.5 metres |

| 1500 paces = a lewa = 7500 Roman feet = 7281 Imp. feet =

2219 metres |

APPENDIX C

Table of Roman monetary values

| 1 gold aureus = 25 silver denarii = 100

bronze sesterii = 400 asses |

| 1 silver denarius = 4 bronze sesterii = 16 asses |

| 1 bronze sestertius = 4 asses |

APPENDIX D

List of Roman Emperors during the Imperial Period from Augustus to

the abandonment of Hadrian’s Wall in 411 AD

| Julio-Claudian Dynasty |

27 BC – 69 AD |

| Augustus |

27 BC – 14 AD |

| Tiberius |

14 – 37 AD |

| Gaius Germanicus (Caligula) |

37 – 41 AD |

| Claudius |

41 – 54 AD |

| Nero |

54 – 68 AD |

| Galba |

68 – 69 AD |

| Otho |

69 AD |

| Vitellius |

69 AD |

| Flavian Dynasty |

69 – 96 AD |

| Vespasian |

69 – 79 AD |

| Titus |

79 – 81 AD |

| Domitian |

81 – 96 AD |

| The Five Good Emperors |

96 – 180 AD |

| Nerva |

98 -117 AD |

| Trajan |

98 -117 AD |

| Hadrian |

117 – 138 AD |

| Antoninus Pius |

138 – 161 AD |

| Marcus Aurelius |

161 – 180 AD |

| Antonine Dynasty

|

138 – 193 AD |

| Antoninus Pius |

138 – 161 AD |

| Marcus Aurelius |

161 – 180 AD |

| with Lucius Verus |

161 – 169 AD |

| Commodus |

177 – 192 AD |

| with Marcus Aurelius |

177 – 180 AD |

| Pertinax |

193 AD |

| Didius Julianus |

193 AD |

| Pescennius Niger |

194 AD |

| Severan Dynasty |

193 – 235 AD |

| Septimus |

193 – 211 AD |

| Caracalla |

211 – 217 AD |

| with Geta |

211 – 121 AD |

| Macrinus |

217 – 218 AD |

| Diadumenianus |

218 AD |

| Elagabalus |

218 – 222 AD |

| Alexander Severus |

222 – 235 AD |

| The Soldier Emperors |

235 – 305 AD |

| Maximinus I |

235 – 238 AD |

| Gordian I and II (in Africa) |

238 AD |

| Balbinus and Pupienus (in Italy) |

238 AD |

| Gordian III |

238 – 244 AD |

| Philip the Arab |

244 – 249 AD |

| Trajan Decius |

249 – 251 AD |

| Trebonianus Gallus (with Volusian) |

251 – 253 AD |

| Aemilianus |

253 AD |

| Gallienus |

253 – 260 AD |

| Gallic Empire (West)

|

|

| following the death of Valerian |

|

| Postumus |

260 -269 AD |

| Laelian |

268 AD |

| Marius |

268 AD |

| Victorinus |

268 – 270 AD |

| Domitianus |

271 AD |

| Tetricus I and II |

270 – 274 AD |

| Palmyrene Empire |

|

| Odenathus |

c.250 -267 AD |

| Valballathus (with Zenobia) |

267 – 272 AD |

| The Soldier Emperors

(continued) |

|

| Claudius II Gothicus |

268 – 270 AD |

| Quintillus |

270 AD |

| Aurelian |

270 – 275 AD |

| Tacitus |

275 – 276 AD |

| Florianus |

276 AD |

| Probus |

276 – 282 AD |

| Carus |

282 – 283 AD |

| Carinus |

283 – 284 AD |

| Numerianus |

283 – 284 AD |

| Dioclatian (and Tetrarchy) |

284 – 305 AD |

| Western Roman Empire

|

|

| Maximianus |

287 – 305 AD |

| Constantinus I |

305 – 306 AD |

| Severus II |

306 – 307 AD |

| Constantine I (The

Great) |

307 – 337 AD |

| Eastern Roman Empire

|

|

| Diocletian |

284 – 305 AD |

| Galerius |

305 – 311 AD |

| Maxentius (Italy) |

306 – 312 AD |

| Maximinus Daia |

309 – 313 AD |

| Licinius |

308 – 324 AD |

| Constantine Dynasty |

337 – 364 AD |

| Empire reunited by Constantine’s defeat

of Licinius |

|

| Constantine II |

337 – 340 AD |

| Constans |

337 – 350 AD |

| Constantius II |

337 – 361 AD |

| Magnentius |

350 – 353 AD |

| Julian |

361 – 363 AD |

| Jovian |

363 – 364 AD |

| Western Roman Empire (after

death of Jovian) |

|

| Valentinian |

364 – 375 AD |

| Gratian |

375 – 383 AD |

| Valentinian II |

375 – 392 AD |

| Eugenius |

392 – 394 AD |

| Honorius |

395 – 423 AD |

| Eastern Roman Empire (after death of

Jovian) |

|

| Valens |

364 – 378 AD |

| Theodosius I |

379 – 395 AD |

| Arcadius |

395 – 408 AD |

| Theodosius II |

408 – 450 AD |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

| 1 |

Breeze, David |

Hadrian’s Wall – English Heritage Guidebook (English

Heritage, 2015) |

| 2 |

Breeze, David |

The Antonine Wall, (Birlinn Ltd., UK, 2009) |

| 3 |

Brock, John F. |

“Four Surveyors of Caesar: Mapping the World”

FIG History Symposium, (FIG Working Week 2012, Rome, Italy) |

| 4 |

Brock, John F. |

“The Great Wall of China: The World’s Greatest Boundary

Monument”,

FIG History Symposium, (XXV FIG Congress 2014, Kuala Lumpur,

Malaysia.) |

| 5 |

Bruce, John Collingwood |

The Wall of Hadrian, With Especial Reference to Recent

Discoveries – Two Lectures (1874) (Kessinger Publishing) |

|

6 |

Burton, Anthony |

Hadrian’s Wall Path – Official National Trail Guide, (Aurum

Press Ltd., London, 2016) |

|

7 |

Campbell, Brian |

The Writings of the Roman Land Surveyors; Introduction, Text

and Commentary, (The Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies,

London, 2000) |

|

8 |

Carter, Geoff |

“Theoretical Structural Archaeology” 40. Reverse engineering

the Vallum (29 November, 2014) |

| 9 |

Collingwood, R. G. (MA, FSA) |

“The Purpose of the Roman Wall”, The Vasculum, The North

Country Quarterly of Science and Local History, Vol. VIII No. 1

October, 1921) |

| 10 |

De La Bedoye |

Guy, Hadrian’s Wall: History and Guide, (Amberley, 2010) |

|

11 |

Dietrich, William |

Hadrian’s Wall: A Novel, (HarperTorch, NY, 2005) |

| 12 |

Dijokiene,Dalia |

“The Impact of Historical Suburbs on the Structural

Development of Cities (based on examples of European

cities)”, Department of Urban Design, Vilnius

Gediminas Technical University |

| 13 |

Eliot, Paul |

Everyday Life of a Soldier on Hadrian’s Wall, (Fonthill

Media, 2015) |

| 14 |

Fields, Nic |

Hadrian’s Wall AD 122-410, (Osprey Publishing Ltd., Oxford,

UK, 2010) |

| 15 |

Fields, Nic |

Rome’s Northern Frontier AD 70-235, (Osprey Publishing Ltd.,

Oxford, UK, 2008) |

|

16 |

Frodsham, Paul |

Hadrian and His Wall, (Northern Heritage Publishing, UK,

2013) |

|

17 |

Geldard, Ed |

Hadrian’s Wall – Edge of an Empire, (The Crowood Press Ltd.,

Wiltshire, 2011) |

| 18 |

Gonzale-Garcia |

A.C. Rodriguez-Anton, A. and Belmonte, J.A., “The

Orientation of Roman Towns in Hispania: Preliminary Results”,

Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, Vol.14 No. 3 (2014),

pp 107-119 |

|

19 |

Hill, Peter |

The Construction of Hadrian’s Wall, (Tempus Publishing Ltd.,

Great Britain, 2006) |

| 20 |

Jones, Clifford |

Hadrian’s Wall: An Archaeological Walking Guide,(The History

Press UK, 2012) |

| 21 |

Mark, Joshua J. |

“Hadrian’s Wall” (15 Nov., 2012.)

www.ancient.eu/Hadrians_Wall/ |

|

22 |

Moorhead |

Sam and Stuttard, David, The Romans Who Shaped Britain

(Thames & Hudson Ltd., London, 2012) |

| 23 |

Mothersole, Jessie |

Hadrian’s Wall, (Lightning Source UK Ltd.) |

| 24 |

Pham, Mylinh Van |

“Hadrian’s Wall: A Study in Function” (2014). Master’s

Thesis, Paper 4509, San Jose State University |

| 25 |

Poulter, John |

Surveying Roman Military Landscapes Across Northern

Britain: The Planning of Romand Dere Street, Hadrian’s Wall and

the Vallum, and the Antonine Wall in Scotland, (Archaeopress and

John Poulter, 2009) |

|

26 |

Richards, Mark |

Hadrian’s Wall Path Map Booklet: 1:25,000 Route Mapping’

(Cicerone Press, 2015) |

| 27 |

Richards, Mark |

The Spirit of Hadrian’s Wall, (Cicerone, Cumbria, 2008) |

| 28 |

Shotter, David C.A. |

The Roman Frontier in Britain: Hadrian’s Wall, the Antonine

Wall and Roman Policy in Scotland, (Carnegie Pub., 1996) |

|

29 |

Simpson, Gerald |

The Turf Wall of Hadrian 1895-1935, (Read Books, 2011) |

| 30 |

Southern, Patricia |

Hadrian’s Wall: Everyday Life on a Roman Frontier, (Amberley

Pub., UK, 2016) |

|

31 |

UNESCO |

“Frontiers of the Roman Empire WHS – Hadrian’s Wall

Management Plan 2008-14 |

| 32 |

Wilmott, Tony |

Hadrian’s Wall – Archaeological Research by English Heritage

1976-2000, (English Heritage, 2009) |

On the net:

| 1 |

Northumberland History – England’s North East, Hadrian’s

Wall:

www.englandsnortheast.co.uk/HadriansWall.html |

| 2 |

“The history of Hadrian’s Wall” – (22/01/2017):

explore-hadrians-wall.com/history/ |

| 3 |

h2g2 – “A Short History of the Roman Legion from the

Republic to the Imperial Era” (created Dec. 5, 2016)

h2g2.com/edited_entry/A87874096 |

BIOGRAPHY

Private land surveyor since 1973, Bachelor of Surveying (UNSW

1978), MA (Egyptology) from Macquarie Uni., Sydney (2000), Registered

Surveyor NSW 1981. Now Director of Brock Surveys at Parramatta (near

Sydney). Papers presented worldwide inc. Egypt, Germany, France, Hong

Kong, Canada, Brunei, New Zealand, Greece, UK, USA, Israel, PNG, Sweden,

Italy, Nigeria, Malaysia, Morocco and Bulgaria. Since 2002 regular

column Downunder Currents, RICS magazine (London) Geomatics World.

Stalwart of FIG Institution: History of Surveying & Measurement awarded

FIG Article of the Month March 2005 for: “Four Surveyors of the Gods:

XVIII Dynasty of New Kingdom Egypt (c.1400 BC)”, January 2012 – “Four

Surveyors of Caesar: Mapping the World” & June 2014 – “The Great Wall of

China: The World’s Greatest Boundary Monument.” Institution of Surveyors

NSW Awards – Halloran Award 1996 for Contributions to Surveying History,

Fellow ISNSW 1990 & 2002 Professional Surveyor of the Year. First

international Life Member of the Surveyors Historical Society (USA),

Rundle Foundation for Egyptian Archaeology & Parramatta Historical

Society, Foundation Member Australian National Maritime Museum & Friends

of National Museum of Australia. Member of Bradman Crest, International

Map Collectors Society, Royal Australian Historical Society, Hills

District Historical Society, Prospect Heritage Trust, Friend of Fossils

(Canowindra), Friends of May’s Hill and St. John’s Cemeteries.

CONTACTS

John Francis Brock

P.O. Box 9159,

HARRIS PARK NSW 2150, AUSTRALIA

Tel: +61(0)414 910 898

Email:

brocksurveys@bigpond.com

|