Article of the Month -

April 2004

|

White Collar Malpractices in Cadastral Surveying and their

Effects on Secure Land Tenure and Sustainable Development

Alick R Mwamza, Zambia

The Author would

like to acknowledge the financial support from the FIG Foundation in

Copenhagen and material support from the Department of Geomatic

Engineering at the University of Zambia

(UNZA), without which carrying out this research would have been very

difficult.

This article in PDF-format.

This article in PDF-format.

1. INTRODUCTION

Since 1992 when the world’s governments realised the need to protect the

environment, sustainable development was adopted as a general principle for

policies and actions that had a bearing in the environment, and one cannot

talk about environment without talking about land on which activities that

affect the environment mostly take place.

Issues of sustainable development strongly depend on surveying, planning

and management of land processes that deal with accessing and securing

tenure of land. Surveying is thus a fundamental activity on one of the major

components of developmental capital; land, with which Zambia as a country is

well endowed. However, in recent years some malpractices have been

encroaching into the professional practice of land surveying.

This research therefore endeavours to bring to the fore white collar

malpractices that have recently crept into the land delivery process which

if left unchecked would have untold effects on our much cherished

environment as has been seen in the mushrooming unplanned settlements where

the developers have no security of tenure at all and their activities on

land are not controlled in any way.

The system that facilitates acquisition of secure tenure on land is

flawed and the resulting security and development is unsustainable. In turn

the development undertaken thereon is not secure. Hence, the developers tend

to put up development that is not long term and which does not conform to

environmental needs for a sustainable earth.

A good cadastral survey approval system is thus a sure measure of

stability in development, as security of tenure of land on which it will

take place is assured. This was already realised at the United Nations 1992

Rio Conference on Environment and Development where the need to protect the

world’s environment was agreed with the concept of Sustainable

Development as a general guiding principle for policies and actions in a

large number of fields and sectors of society [FIG Agenda 21].

The World Commission on Environment and Development defined sustainable

development in their report on “Our Common Future” as, “Development that

meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future

generations to meet their own needs” [FIG Agenda 21]. This meant

protecting the natural environment and improving the social situation of the

poor and combating poverty.

Land surveying is therefore deeply involved in issues of profound

importance to sustainable development to improve the social situation of the

poor by combating poverty.

One such issue is that of land delivery and security of tenure without

which sustainable development cannot be realised. The issuance of a

Certificate of Title to land for a 99-year lease period is based on an

approved survey diagram compiled from a field survey carried out by a Land

Surveyor. In this context a Land Surveyor is one who is licensed to do so by

the Survey Control Board [Land Survey Act]. The Surveyor General or his

appointed Government Surveyors approves the survey after a rigorous

examination of the survey records submitted by the land surveyor. A

Government Surveyor is a licensed Land Surveyor who is in government

employment and is so appointed by the Surveyor General [Land Survey Act].

This research therefore looked at the current system of cadastral

surveying and its approval so as to identify any flaws and their effects on

secure land tenure and sustainable development and recommends feasible

remedies to mitigate the effects.

This research is of particular importance to sustainable development in

that it hinges on the security of tenure, which in itself is a critical

factor for sustainable development without which the developer may not

sustainably develop the land.

It is hoped that the findings of this research would help greatly enhance

the land delivery system that would be free of potential conflicts and

secure by an unquestionable Certificate of Title thereby guaranteeing

environmentally friendly development.

2. LAND HOLDING IN ZAMBIA

All land in Zambia was held under customary laws before the arrival of

the white settlers. This changed with the arrival of the colonialists who

wanted to hold land using the system they left at home, the British legal

system [Mulolwa 2002]. This brought in what was then called crown land,

which was held either on Freehold or leasehold, and native land under

customary laws.

Today land is still administered with this dual system with crown land

having changed its name to state land. In 1975, all freehold estates were

converted to 99-year leases through enactment of the Land (conversion of

titles) Act. Land could thus not be sold except for the improvements on it.

As such land in Zambia is held on leasehold in state land and under

customary laws in customary areas. However there is a provision for

converting customary land into state land with the consent of the customary

leaders (chiefs).

Land may also be held on a fourteen-year lease using just a sketch to

generally describe the land parcel in question. This lease is normally

looked at as just a facilitating tool for development as arrangements for a

longer lease are being made. There is also a 30 year lease given out based

on a sketch plan in resettlement schemes. A 30-year occupancy license is

also given within housing improvement areas under the Housing (Statutory and

Improvement Areas) Act, 1975. Occupancy licenses are given out by councils

who hold a block title to such land.

The longer lease is for a period of 99 years and can only be granted

after an accurate survey of the land parcel has been carried out, hence the

need for a survey diagram.

3. NEED FOR A SURVEY DIAGRAM

A survey diagram is one of the three cadastral plans that are part of the

survey records for a particular survey of a land parcel for purposes of

obtaining a certificate of title.

It is thus a document that contains geometrical, numerical and verbal

descriptions of one or more parcels of land, the boundaries of which have

been surveyed by a land surveyor and which document has been signed by such

land surveyor or which has been certified by a government surveyor as having

been compiled from approved records of a survey or surveys carried out by

one or more land surveyors [Land Survey Act]. It includes any document,

which prior to the commencement of the Land Survey Act had been accepted as

a diagram in the Lands and Deeds Registry or in the office of the Surveyor

General or his predecessors.

A diagram may therefore be needed when:

- One needs to get a 99-year lease for a newly offered parcel of land.

In this case a new survey is undertaken for the purpose.

- One needs to transfer from a 14-year lease to a 99-year lease. In this

case a new survey is undertaken for the purpose.

- One needs a separate title for a subdivision from a parent parcel of

land. In this case a new survey is undertaken to excise off a part of an

existing parcel of land.

- One needs to replace a lost 99-year lease. In this case a so-called

duplicate title is issued using diagrams that a recompiled from the

original approved survey records held by the Surveyor General. The

compiled diagrams are called Certified True Copies (CTCs) whose use is

conferred by authority under section 33 of the Land Survey Act.

4. CADASTRAL SURVEYING

Cadastral Surveying is concerned with the charting of land to accurately

define its boundaries for purposes of obtaining a certificate of title to

that land. In Zambia, cadastral surveying is governed by the Land Survey Act

under which a Survey Control Board, which regulates the practice of

Cadastral Surveying, is constituted.

The Land Survey Act restricts the practice of cadastral surveying to only

licensed surveyors who are called Land Surveyors. The Surveyor General may

appoint Land Surveyors in government employment as Government Surveyors.

Government Surveyors are the ones who approve cadastral surveys on behalf of

the Surveyor General, who is the top most Government Surveyor.

5. THE CADASTRAL SURVEY APPROVAL SYSTEM

|

Since the cadastral diagram is a legal document, the

survey from which it is compiled is examined in the examinations section

of the Survey Department. The Chief Examiner heads this section. He has

about six other examiners under him.

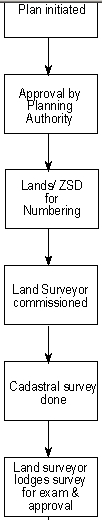

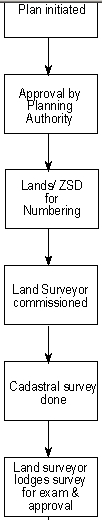

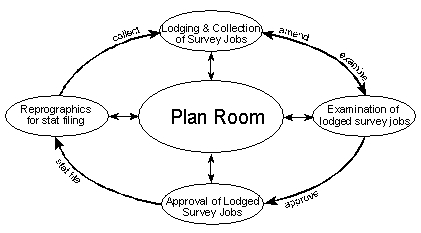

5.1 Flow of a Survey Job for Examination

Once the planning authority has approved development of particular

parcels of land, that plan is forwarded to the Ministry of Lands for

numbering after which advice on commissioning land surveyors to carry

out the survey is given to the client. The commissioned land surveyor

then carries out the survey, prepares the necessary records and lodges

them for examination at the Zambia Survey Department (ZSD).

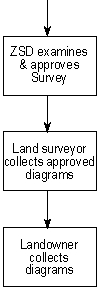

After examinations, the job is either returned to the land surveyor

for corrections or it’s passed on to the Government Surveyor for

approval. The Land surveyor then collects the approved survey diagrams

and hands them over to the client who uses them to request for their

Certificate of Title from the Lands Department.

All other materials (the written survey report, field book,

computations book, working plan and general plan) become public property

and remain with ZSD. These are used to update plans and for general

consultation by other land surveyors and others who may need the same

information. These records are kept in the Plan Room.

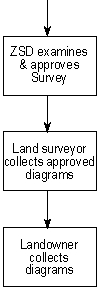

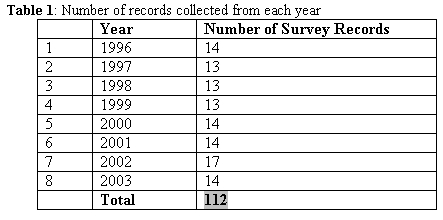

5.2 The Plan Room

The Plan Room is so called since this is where all the cadastral

plans and records are kept. At present all the data is in hard copy

form. Any data search for cadastral survey records takes place in the

plan room. The plan room also acts as a reception area for the ZSD. It

is usually the first point of call for all sorts of clients to the ZSD.

It is in the Plan Room that numbering of plans is done on request by

the Lands Department. Requests for Certified True Copies (CTCs) of

approved diagrams are also made in the Plan Room. The Plan Room, in

short, handles all sorts of requests pertaining to cadastral surveys and

filters them to particular sections, which deal with them.

It is therefore in the plan room that land surveyors lodge their jobs

for examinations and collect them after examinations. The plan room is

the focal point in the movement of the survey job for examination in

that after the job has been lodged for examination, it is registered and

given a survey record (SR) number and then forwarded to the examinations

section (Chief Examiner). After examinations, with necessary comments

(either return to land surveyor or pass to approval) the job is brought

back to the plan room where it’s forwarded to the next person in line.

FIG 1. A survey job's flow from planning to

collection of approved diagrams. |

After approval by the Government Surveyor, the Plan Room forwards the job

to the Reprographic Section to make a disaster copy for every approved

diagram, a process called “stat filing”, after which the job’s computer

records in the alphanumeric database are updated so as to now show the

survey details of that previously unsurveyed land. These are details like

diagram number, survey record number, land surveyor, extent, date surveyed

and so on.

After all this, the survey diagrams are then ready for collection by the

land surveyor who lodged them.

The plan room falls under the examinations section and is headed by an

examiner who is called the Plan Room Supervisor.

Fig. 2. Plan Room as the focal point in the survey job examination

process.

5.3 The Examinations Section

This section, which is headed by the Chief Examiner, who reports to the

Assistant Surveyor General in charge of Cadastral Services, is responsible

for scrutinising cadastral survey jobs before a government surveyor can

approve the survey.

The examination focuses on the correctness of the methods used,

preparation of reports and plans and whether carried out in accordance with

the Land Survey Act and its regulations. The job is either passed on for

approval or retuned to the land surveyor for amendments as per findings of

the examiner.

After being lodged, the survey job is put in a durable folder called a

Jacket upon which every officer who handles a particular part of the job

endorses his or her signature and comment. The contents of the Jacket are

also endorsed on it.

In addition, when survey jobs are lodged for examination and brought to

the Chief Examiner, he enters them in his register and distributes them to

his examiners who report back their findings to him so that he keeps track

of the examinations process noting the findings in his register. Jobs for

examination are therefore supposed to enter and exit the section through the

Chief Examiner.

6. THE PROBLEMS IN THE SYSTEM

The research focused on the period 1996 – 2003 for these malpractices

became noticed after land transactions were given monetary value. Previously

only developments on land could be sold and not the land itself on which the

developments were. This addition of monetary value to land became more

visible with the sale of government, parastatal organisations and council

houses to individuals who in turn sold them at inflated prices compared to

what they got them at.

At the same time there was an immeasurable demand for land to allocate to

those that did not benefit from the sale of houses. Prospective landowners

were thus ready to lay their hands on anything that appeared to be vacant

land at all costs. On the other hand, there was a cadre of prospective

malpractitioners ready to pounce both on the potholed system and the

desperate prospective landowners.

The major problem in the system now is therefore that procedures are not

followed at almost every level, leaving a lot of room for malpractices and

infiltration of the system by malpractitioners who survive by destabilising

the system further. This problem is not just a ZSD problem but also spreads

to other Departments of the Ministry since there is no system for counter

checking what is purported to come from the other Departments.

Consequently fictitious surveys, surveys carried out in offices,

existence of diagrams for non-existent land parcels and indiscriminate

issuance of CTCs through total abuse of section 33 of the Land Survey Act

became immensely noticeable. These malpractices thus gave rise to yet

another problem of rampant disappearance of survey records, mostly involving

such dubious surveys.

7. METHODOLOGY

The research started by reviewing a number of related articles to learn

and see what might have been done before in Zambia.

Minango (1998) in his thesis report outlined that, Dale (1976) included a

review of the cadastral system in Zambia in chapter 10 of his book; Lilje

and Nilsson (1976) looked at the backlog (reasons and consequences) of

cadastral surveys and their future demand in Zambia in a Swedesurvey

consultancy report; Mvunga (1980) traced the origins and development of land

tenure systems in Zambia; Bruce and Dorner (1982) looked at land tenure

issues in perspective, equity and productivity; Kagedal and Fagersten (1986)

delved into appropriate mapping techniques for land held under customary

tenure system; Fox (1989) covered issues of land delivery and Chileshe

(1994) looked at a low cost approach to cadastre and land registration for

land under customary tenure with emphasis on data acquisition.

Chilufya (1997) in looking at a possibility of an integrated cadastral

and land registration information system noted that delays in survey records

examinations were due to lack of trust the system had in Land Surveyors. In

other words, he alluded to the existence of white-collar malpractices in the

system, which one would say the examinations process sought to eliminate. He

recommended punishment for the erring land surveyors according to the law to

instil trust in the work they did. Chilufya (1997) also recommended that the

number of duplicate copies of plans maintained by the system needed to be

reduced. This pointed to the fact that the system cannot adequately monitor

activities based on these duplicate copies of plans due to their numbers and

might therefore create a fertile ground for the noted malpractices in the

system.

In addressing the issue of delayed examination of cadastral surveys,

Mulolwa (2002) recommends the use of an elaborate standard survey job

submission form with adequate information to aid quick determination of its

quality and hence approval.

The Lands Tribunal, set up under the Lands Act of 1995 to expeditiously

handle all matters relating to land, has so far not handled any dispute

which could directly be attributed to the problem of white collar

malpractices in cadastral surveying.

It can therefore be seen that no research has solely been dedicated to

identifying land survey malpractices inherent in the approval system or

indeed the registration system, let alone the effects of these malpractices

to secure land tenure and sustainable development. There was therefore need

for this research.

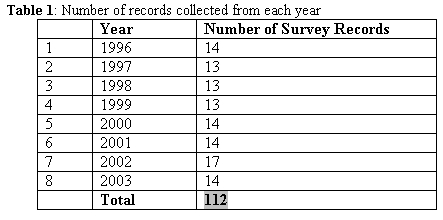

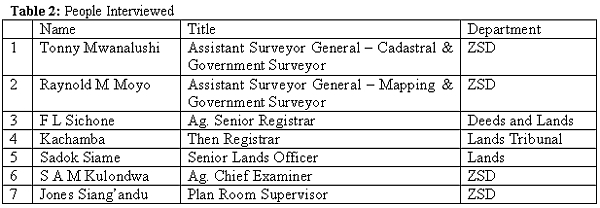

After literature review 112 survey records were randomly picked from the

Plan Room covering the period 1996 – 2003 (see table 1 and appendix 1). From

these records the following information was collected; parcel number,

examiner, survey record number and who carried out the survey (government or

private).

Since each surveyed and approved plan has a Survey Record (SR) number,

each parcel has an associated SR number. Accordingly, using parcel numbers

from the randomly selected survey records, a search was conducted in the

computer database to come up with the survey record numbers for those

parcels. Another check was also performed using the survey record numbers to

see if the survey records under scrutiny were for the same parcels of land.

This was done to determine the extent of the problem (see appendices 2 and

3).

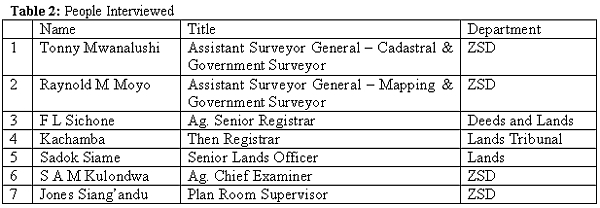

Interviews with some system operators were also conducted through which

some cases of these malpractices were identified. These interviews and mere

observations also helped understand the system of cadastral survey approval

and the public reception and complaints procedure now in place (see Table

2).

However, instead of focusing on who the perpetrators were the research

focused on identifying the flaws in the system and how they could be

remedied. This was necessitated by the fact that it was difficult to extract

information from people at a time when the country and the Ministry of Lands

in particular was embroiled in issues of corruption, which in essence are

the root cause of the very malpractices the research was focusing on. A

government task force pursuing perpetrators of economic plunder was already

in place and it was difficult for people to look at this research as an

exercise aimed at improving the land delivery system for sustainable

development and not a conduit for investigating people for prosecution.

8. FINDINGS

8.1 Record Searches

The searches done on computer using parcel numbers generated same survey

record numbers for most of the parcels, i.e. 76 of 112 representing 68%.

Therefore 68% exist both on ground and in the alphanumeric database. The

other 32% (36 of 112) generated comments ‘exist’ (23) and ‘not

exist’ (13). This is despite these survey records existing and being as

old as 5 years after approval. A possible explanation was given that:

- ‘exist’ means the parcel was proposed (numbered) to be surveyed

but may not have been surveyed yet, or if surveyed is not yet updated in

the database.

- ‘not exist’ means that the parcel was not proposed (numbered)

to be surveyed in the first place. As such it does not even exist in the

database.

The search by SR numbers did not yield much as the computer database

available has no capability to search using SR numbers. This was thus done

using the examinations register, which is very outdated.

8.2 Interviews and Observations

Through interviews, it was also discovered that:

- there is abuse of section 33 of the Land Survey Act. Section 33 allows

a government surveyor to approve a diagram or general plan if the same was

framed from approved survey records filed with the Surveyor General’s

Office (ZSD) or registered in the Deeds Registry without the signature

thereon of the land surveyor who signed the original general plan or

diagram if he is not available or unreasonably refuses to sign the general

plan or diagram so framed.

Through the use of this section fictitious or office surveys have been

conceived and diagrams produced with forged approving signatures or indeed

correctly signed by the unsuspecting government surveyor. Such surveys may

even bear record numbers of other parcels just to make them look complete

and real. This scenario presents itself on either a real parcel or indeed

a non-existent parcel.

- Existing parcels are usually those that were previously held on

14-year lease using a sketch plan as a description of the land parcel.

The malpractitioners then just sit in the office and scale off

coordinates from a topographic map and insert them on a diagram and use

other record numbers on it. It thus looks authentic and is presented for

approval.

- Non-existent parcels are used in the case of a desperate prospective

buyer who is promised a one-stop shop in acquiring the necessary

documentation for the promised parcel of land.

- There is indiscriminate production of CTCs using the same section 33.

- This is sometimes done to circumvent paying of survey fee due to a

land surveyor. In which case the malpractitioner pockets the small fee

for production of a dubious CTC.

- CTCs produced to facilitate a dubious transaction of selling one

parcel of land to more than one buyer and issuing all of them with

diagrams.

- Survey records pertaining to questionable diagrams disappear from the

plan room to obliterate incriminating evidence.

It was also discovered that persons who masquerade as land surveyors

perpetrate most of these malpractices aided by land surveyors who sometimes

endorse their work as authentic when not, at a small fee, the so-called

signing fee.

The plan room though acting as a reception area to ZSD is actually not.

As such a lot of confusion reigns presenting a fertile ground for the growth

of these malpractices. Owing to the plan room acting as a public reception

area to ZSD, it is difficult to monitor the movement of survey records,

which sometimes fall in wrong hands. Some officers in the Department also

personalise some survey records denying land surveyors and other interested

parties access to the same. Landowners instead of the land surveyor they

commissioned also usually collect diagrams directly from the plan room.

Movement of lodged survey jobs is not properly monitored such that some

jobs go straight to certain examiners with interest in them, a situation

which compromises quality of work produced. In fact it is in such cases were

records disappear soon after the job is approved. As such it is even

difficult for the chief examiner to know which jobs have come in and gone

out of his section for whatever reason.

At the ministry level it was found that there is no way of verifying what

Lands Department receives from ZSD as the diagrams are presented by the

landowners. The same is true for the Lands and Deeds Registry. Although

there exists an alphanumeric database in the ministry on matters of land,

most line officers have no access to it.

These flaws therefore make the perpetrated malpractices not easily

detectable at the right time at the right stage to quickly nip them in the

bud.

9. ANALYSIS OF FINDINGS

9.1 Record Searches

Searches that were conducted on randomly picked survey records came up

with 20.5% of records that were classified as existing but had not been

updated and 11.6% of the records that were classified as not existing.

- The records labelled ‘exist’ are parcels that were numbered but not

surveyed according to the computer database. Yet some of the parcels had

their surveys approved 5 years ago.

- The records labelled ‘not exist’ are for parcels that were numbered

and not indicated so in the database. They are thus not even supposed to

be surveyed according to the database records. Yet again their survey

records were approved.

There is only one computer terminal in the plan room from where the

alphanumeric database is updated and an excuse that it is inadequate may

therefore be advanced. Whereas this is true, it does not hold water in that

the so much talked about backlog cannot be properly ascertained since recent

records are updated and old ones not.

Therefore this anomaly in a system that is supposed to deliver secure

land tenure comes about because of lack of a clear-cut monitoring mechanism

to check that the flow of plans for numbering and approved survey records is

according to procedure. This is so in that there seem not to be clearly

defined roles for plan room personnel on who should make database updates

although both plan numbering and updating of surveyed parcels is done in the

plan room. The graphic updates done by the cadastral drawing office,

probably at the same time, cannot be said to cause the delay in the

alphanumeric database.

This lack of a monitoring mechanism thus leaves room for anyone to pick

the numbered plans or survey records before they are updated with or without

permission. The 32.1% of ‘exist’ and ‘not exist’ records could

therefore be as a result of malpractices.

Recommendations

- Clearly define the roles on who should be charged with the task of

updating the database. Such a person should also have unique rights to the

alphanumeric database, which all others might not be assigned.

- Increase the number of terminals in the plan room for this and other

purposes so as to ensure uninterrupted access to the database for the

person(s) carrying out the updates.

- Clearly define what kind of information is obtainable in the plan room

and from the Department of Lands so as to free the plan room from an

influx of people looking for information they could easily obtain from

Lands. This could be done by restricting the kind of information available

to the plan room to only survey issues.

- Put in place a clear watertight mechanism for monitoring the flow of

jobs handled in the plan room. Mulolwa’s (2002) integrated land delivery

architecture includes a job flow-monitoring module across the entire

process. Such a mechanism must have no room for shortcuts. This can easily

be done by ensuring that the current scenario where all survey jobs enter

and exit through the plan room only after all updates are completed.

- In case of survey jobs lodged for examinations, a monthly

reconciliation of the plan room records and actual jobs handled in the

examination section must be undertaken to account for jobs that circumvent

normal procedure.

9.2 Indiscriminate Use of Section 33 of Land Survey Act

Most if not all of the fictitious diagrams produced involve the use of a

name of a land surveyor who was or is in government employment. This is

because the loose application of this section in ZSD has largely facilitated

the malpractitioners use of this section. ZSD does not have enough licensed

surveyors and so it just uses names of the few available licensed surveyors

even for jobs done without their supervision, which is a clear contravention

of the provisions of the Land Survey Act. Such diagrams, which are not

signed by the land surveyor but just bear the land surveyor’s name, are many

from jobs carried out by ZSD in its 9 Regional Offices.

This is a flaw, which has been exploited to the fullest since one does

not need a land surveyor’s signature but just typing in the land surveyor’s

name suffices even for false surveys. The law only provides for use of

section 33 in recompilation involving previously approved survey records.

Section 33 reads, in part, that “provided that a general plan or

diagram may be approved if it has been framed from an approved general plan

or from an approved diagram or diagrams or from approved Survey Records

filed in the Surveyor General’s office or registered in the Registry,

without the signature thereon of the land surveyor who signed the original

general plan or diagram if he is not available or unreasonably refuses to

sign the general plan or diagram so framed”. It makes no mention of a

new survey being approved using the same section.

In fact section 33(2)a is categorical on the matter and states, “subject

to the provisions of section thirty-four, no general thereof plan or diagram

shall be approved unless it is prepared under the direction of and signed by

the land surveyor or land surveyors who carried out the respective survey”.

Section 34 only allows approval of unsigned records if they are for

consolidation purposes or boundary realignment only.

Recommendations

- ZSD must adhere to the provisions of the law. The reason why ZSD uses

the name of any land surveyor in government employment is not among those

provided for under section 33 of the Land Survey Act. ZSD must therefore

ensure that every Regional Officer in Charge is a land surveyor.

- To achieve the level of a land surveyor for every Regional Office, ZSD

must have a deliberate policy of grooming its young surveyors to obtain

licenses after a well-designed apprenticeship period.

- The Survey Control Board, though chaired by the Surveyor General must

clamp down on ZSD for indiscriminately using section 33 of the Land Survey

Act and contravening the law.

- In the meantime ZSD must restrict the use of section 33 to authority

given by the Assistant Surveyor General – Cadastral Services or the

Surveyor General only.

- For surveys involving living land surveyors, every effort must be

taken to ensure that they sign the documents as land surveyors are almost

always at ZSD looking for information to use in their work.

- The Land Survey Act, which was enacted in 1960, urgently needs a

severe surgery to rid it of undesirable clauses that facilitate

malpractices and infuse in new clauses that befit the 21st Century to take

care of the changing land administration and surveying technologies.

9.3 Indiscriminate Production of CTCs

Many people in Zambia dot not want to pay survey fees, which in fact, are

not so high. They thus trek to the plan room in the hope that they can

bargain for something less. When it is discovered that the parcel was

already surveyed but the owner says can only pay a small amount, CTCs are

usually the answer using the same notorious section 33 without the consent

of the land surveyor who could still be holding on to the diagrams waiting

for the no show parcel owner.

A mechanism is in place to ensure that the land surveyor accents to the

production of CTCs but it is not water tight.

Recommendations

- Applications for CTCs must go through the land surveyor who originally

carried out the survey to the Surveyor General. Where the land surveyor is

not available or unreasonably refuses to accent, then section 33 may come

into play.

- Reasons for production of CTCs must be properly laid out with

supporting documentation before accepting to issue them.

9.4 Missing Survey Records

Normally it is the records of dubious surveys, which go missing to erase

evidence of the same although some records are just personalised by some

people especially officers in ZSD. The reason being that they carry out

unauthorised surveys in certain areas but also simply for the love of

creating mini archives in their offices.

Recommendations

- A flawless job tracking mechanism is required to ensure that a jacket

position in the whole system is known at any point in time.

- Survey records must only leave the plan room after being signed for

indicating name, date and reason for collection, otherwise consult within

the plan room. At the end of the week an officer of the plan room charged

with the monitoring of the movement of the records must make a follow-up.

- Collection of and consulting of certain records must be restricted to

a specified group of people only such as land surveyors and line officers

in the ZSD.

- Only land surveyors or their authorised agents must be allowed to

collect diagrams from the plan room after approval.

- Clear and clean up the Plan Room. It is currently in a mess.

- Create a separate data review and printing section.

- Employ qualified staff in data and information management to run the

Plan Room.

9.5 Public Reception and Complaints Procedure

There is literally no public reception and complaints procedure system in

place. It is even difficult for someone coming to the Ministry for the first

time to find their way. Apart from the plan room functioning both as a

cadastral survey information archive and reception for land surveyors

lodging and collecting their jobs, it also acts as a public reception office

for not only the ZSD but also other Departments as people usually call there

first before being directed to the right office. This has bred a lot of

confusion in the whole system in that the roles of the plan room are not

well known as such and monitoring of its activities are difficult when there

is always an influx of the public looking for this or that.

Recommendations

- The Plan Room must be a cadastral survey information archive and a

specialised reception office for services needed by land surveyors and

line officers in ZSD. It will then be able to offer services that it

should to the right people and at the same time be able to monitor its

activities better than now.

- There must be therefore another public reception office for the ZSD or

Ministry that can act as a filter for all clients that visit ZSD or the

Ministry. This will also help in reducing incidences of tempting offerings

to various officers who at the moment directly come into contact with the

public. Mulolwa’s (2002) integrated land delivery architecture

incorporates such a front desk idea.

9.6 Checks within the Ministry

Knowing the output of other line Departments in the ministry is very

important if a conflict free product (title) is to be realised and dubious

records are to be quickly detected. At the moment the Lands Department that

receives the approved diagram to prepare a certificate of title, does not

know whether what they receive is authentic or not. As such there are even

cases where titles were prepared based on dubious diagrams.

Recommendations

- There is need for cross Department awareness campaigns to simply

enlighten those directly or indirectly receiving information or documents

from other Departments, which are inputs in their work. They need to know

what to expect and in what form. That way they will be able to tell the

difference between an authentic document and a dubious one.

- The present database system must be enhanced into an integrated GIS,

which both Chilufya (1997) and Mulowa (2002) advocate. Through such a

system, which integrates survey graphic data and land records, each

operator in the system of land delivery will have access to view the

records they need and take their action based on it. Certain safeguards

can be built in into the system to ensure integrity of information

therein.

For example, information about a parcel of land could be available from

the time an offer is made with additional information being added as it is

being generated such that at every stage any operator in the system would

know at what stage the process for a particular parcel is, thereby enabling

them to make an informed decision and advise the client accordingly. And

since information shall be input by people given rights to do so cases of

fraud will be easily detected and nipped. Decision-making shall also be

greatly enhanced with such an approach.

9.7 Unqualified People Carrying out Cadastral Surveys

Most of the malpractices in cadastral surveying are perpetrated by people

who are not qualified to do the job. These are normally people in the allied

professions who in the course of their work come across cadastral related

work. But instead of referring it to the experts they take it up and use

fellow unqualified people who use short cuts to get to the product required.

Such people have flourished because of the laxity in enforcing the law and

the sheer ignorance of those that give them such jobs.

Recommendations

- Enforce the provisions of the Land Survey Act by prosecuting those

that contravene the law.

- Mount awareness campaigns for the public using all effective media

channels to enlighten the public on the need to use land surveyors for

cadastral surveys. Further enlighten the public on what it takes to

produce a diagram and consequences of using unqualified people and dubious

methods to obtain a survey diagram. It is important to tell the public

that Cheap is usually expensive since the job, in case of a fictitious

survey, must be redone at the owners cost.

- Encourage land surveyors to get involved in educating the public,

especially the venerable groups e.g. women, on the process of getting

title to land as their contribution to society through which society’s

attitude could be influenced towards the concept of sustainable

development [FIG Agenda 21]. Such activities must therefore be recognised

by professional bodies as part of CPDs. Land surveyors must socially

integrate themselves in societies they live so that the public know what

they do best. Such involvement of land surveyors in public awareness

campaigns will thus go a long way in contributing to the achievement of

FIG Agenda 21.

10. EFFECTS ON SECURE TENURE AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

The effects of these white-collar malpractices in cadastral surveying are

immense and costly. In most cases land developers have had to lose out on

developmental projects they started on land that was later found to have

irregular documentation. In some cases building structures have had to be

demolished with no compensation at all or well-cleared farmland repossessed.

All because short cuts in the process were sought through resorting to

malpractices.

For example within this year not only was property lost in the Kalikiliki

demolitions, but also life. In 1991 and 2002 property was lost in the

Kanyama and Kamanga demolitions [Kalikiliki,

Kanyama and Kamanga are all unplanned settlements in Lusaka].

All because of the development were not secure and therefore unsustainable.

Had all these been secure with title based on properly executed cadastral

surveys, the loss could have been avoided.

In a country that is grappling with a high poverty levels, such loss of

scare resources through malpractices in the process of land delivery has a

very devastating effect in that the majority of the people are denied access

to land and security of tenure, which are very important prerequisites for

the provision of shelter for all. Consequently this translates into a great

denial of the development of sustainable human settlements in a country

where there is virtually no residual income. Hence a denial to break the

vicious circle of poverty which, is continually killing our society [FIG

Agenda 21].

In an effort to role back malaria, mosquito-spraying campaigns in

unplanned settlements failed due to lack of proper maps to plan and monitor

the process. Maps in such areas are usually a product of cadastral surveys.

Disease control is therefore a difficult task where illegality reigns.

Where landowners are spared of repossession or demolition, they have had

to foot the bill for a resurvey to correct the wrong, while losing out on

their first or indeed second payment of the dubious survey. All this at the

cost of diverting developmental resources into a process that could have

been done right the first time. The administrator of a named farm contracted

2 others who did not deliver the required service before she settled for the

author and paid all the three.

In cases where development takes place the economic effects are also

immeasurable since it becomes extremely difficult to turn such assets into

liquid capital thereby hindering acquisition of the much-needed capital for

new investments. Correction is usually at great cost both in terms of direct

payments for correction as well as in terms of loss of what might have been

a lifetime investment opportunity.

The greatest effect is that of loss of confidence in the land delivery

system by the main players such as development financing institutions. When

the documents that guarantee security of tenure become questionable,

securing financing opportunities for developmental projects becomes

difficult. Where they are accessed, it is again at an additional cost

because such players will ask for or carryout additional checks before

rendering any assistance.

In addition when confidence in a system is lost, illegality takes root

[Mulolwa 2002]. This then breeds anarchy in that development is unplanned

and haphazard. In such a scenario it therefore becomes difficult for central

or local government to control development in this age where even illegal

developers can seek protection of the law leading to lengthy and costly

legal battles in courts of law. Moreover, environmental concerns cannot be

addressed when development itself cannot be controlled. Even the much needed

provision of services and collection of revenue is difficult in such

circumstances.

All these effects sum up to an unsustainable development as everybody

loses confidence in the system. Environmentally, this has led to development

that does not take into account the well being of the surroundings within

which it is occurring. Hence degrading it to levels, which require diversion

of huge amounts of resources to correct. Yet such diverted resources could

otherwise be used to sustain society.

For example, the Kalikiliki Dam, at one time the home of a once vibrant

Lusaka Yachting Club is slowing being suffocated by encroachments of illegal

settlements. Many dambo (swampy) areas are now illegally built up;

disturbing the natural environment of any aquatic life there was in these

areas.

11. OVERALL RECOMMENDATIONS

Secure and sustainable development can only come about when there is

order in the land delivery system. At the moment there is a lot of anarchy

in this process that needs to be addressed urgently. Knowing that security

of tenure is a critical factor of sustainable development must propel us

further to ensure that the system that delivers that security is flawless to

build confidence and facilitate economic development.

The operations of the Plan Room and Examinations Section need to be

streamlined to make the survey diagram approval process watertight. In

addition, there is need to separate the plan room from a public gallery that

it now seems to be by providing a separate general public reception office.

The Surveyor General, the Assistant Surveyor General – Cadastral Services

and the Government Surveyor approving cadastral surveys must have access to

the enhanced database records (GIS) so that they are better informed as they

carry out their tasks. The same is true for all desk officers in Lands and

Registry Departments. This will only have an impact if the present system is

developed into a more transparent GIS that shall afford particular officers

only that information they need to work on or view. There is therefore need

to reengineer the present system on the lines recommended by Mulolwa (2002)

and Chilufya (1997). Such a GIS will stem a lot of malpractices with its

inbuilt safeguards, which to some extent the present system is lacking.

There is also an urgent need to overhaul the Land Survey Act, CAP 188,

and related legislation to facilitate smoothening the process of the entire

cadastral surveying system. In its current state, the Act is somewhat a

bottleneck in the land delivery system (The proposed amendments that were

proposed some 3 years ago have been overtaken by events). In line with the

pledge made in the 1996 Land Policy Document, the Ministry must facilitate a

quick review of this Act.

ZSD must stop abusing section 33 of the Land Survey Act. It has been a

major facilitator of the fictitious surveys that have occurred. ZSD must

therefore embark on retraining their young land surveyors towards getting

licensed. An increased number of land surveyors, from the present 30 country

wide, will also help curtail this dirty trend of mushrooming fictitious

surveys.

The Survey Control Board must also ensure that this scenario of about one

land surveyor per 350,000 inhabitants is greatly improved by devising

deliberate apprenticeship programmes for the profession. It is not enough to

just rely on a natural flow events when we are a country in crisis. The

Survey Control Board must also clamp down on all illegal activities in the

profession regardless of the perpetrators.

12. CONCLUSION

Poverty is a chronic disease eating away the fabric of our society and

affects both the haves and the have-nots. In Zambia, the single resource

that we have in abundance is land. Everywhere in the world economic

activities take place or start taking place on land. For us to economically

prosper, there must be security for rights held in land by various players

in the economy so as to facilitate economically sustainable development that

has the well being of the environment in mind.

This is achievable through the involvement of the land surveyor in

fulfilling his or her part in a conflict free land delivery process by

providing reliable survey data upon which a certificate of title, that

ensures secure holding in land, is based.

When this process is infested by malpractices security of tenure on which

sustainable development and hence economic empowerment depends, shall remain

a pipe dream and our society shall forever remain impoverished despite the

abundance of the major component of developmental capital – land. This

research has brought out issues that were previously just being talked about

in passing so that something can begin being done to nip this budding

problem before it gets out of hand.

Sustainable development depends on access to appropriate information at

the right time in the right form for critical decisions to be made. Some of

this information is delivered through cadastral surveying, which is in turn

used for property tax, land rent and rates collection, location of utilities

installations and provision of vital services such as ambulance and fire

services. The Lusaka Water and Sewerage Company limited, has shown that use

of cadastral information could be beneficial. Using cadastral maps based

GIS, the utility is able to sustain its operations through a billing system

that catches all its clients by location, timely location of faults to

properly maintain its infrastructure and to timely plan future developments

with an environmental friendly touch. These are some of the benefits of

properly functioning cadastral surveying system.

It is therefore hoped that the findings and recommendations of this

research shall become a vital piece in our quest to improve the

administrative, technical and legal aspects involved in the land delivery

process, especially those addressed in this research.

It is also hoped that, having sanctioned this research, the Surveyor

General shall employ its findings and recommendations into improving the

survey part of the land delivery system. The Ministry at large should also

use these findings to streamline the cross Department counter checking

system before using a particular product as an input in their own part of

the land delivery system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Author would like to acknowledge the financial support from the FIG

Foundation in Copenhagen and material support from the Department of

Geomatic Engineering at the University of Zambia (UNZA), without which

carrying out this research would have been very difficult. The willingness

to give information by all those interviewed is also highly acknowledged as

they made the research successful. The efforts, encouragement and assistance

of Chama Manda and Yamikani Mwanza in carrying out this

research are equally highly appreciated too. The encouragement the author

received from the Surveyor General, his assistant for cadastral services,

the School of Engineering Research Coordinator, UNZA and the President of

the Surveyors Institute of Zambia (SIZ) is also acknowledged. Dr A

Mulolwa is being acknowledged for reviewing this report at short notice

and indeed all those who contributed directly and indirectly.

REFERENCES

- Chileshe R A., 1994, A Low cost approach to Cadastral and Land

Registration for the customary Lands of Zambia with emphasis on data

acquisition, MSc Thesis, ITC, Enschede.

- Chilufya S M., 1997, From Manual to Integrated Cadastral and Land

Registration Information Systems – A Zambian New Legal Challenge, MSc

Thesis, ITC, Enschede.

- Dale P F., 1976, Cadastral Surveys within the Commonwealth, HM

Stationery Office.

- FIG Publication No. 23, FIG Agenda 21 2001 E ISBN 87-90907-07-8

- Land Survey Act CAP 188 of the 1995 Edition of the Laws of Zambia.

- Land (Conversion of Titles) Act, 1975, Laws of Zambia

- Housing (Statutory Improvement Areas) Act, 1975, Laws of Zambia

- Minango J C., 1998, Introducing a “Progressive” cadastre at the

Village as a Toll for Improving Land Delivery – A Case Study of the

Customary Areas of Zambia, MSc Thesis, ITC, Enschede.

- Ministry of Lands, 1996, Land Policy Document, Government Printers.

- Mulolwa A., 2002, Intergrated Land Delivery: Towards improving Land

Administration in Zambia, DUP Science, Delft University Press

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

The following team carried out this research.

Principal Researcher, Mwanza, Alick R (B.Eng, MSc). Lecturer in

the Department of Geomatic Engineering at the University of Zambia and a

holder of a Cadastral Surveying Practising License. Currently Vice President

of the Surveyors Institute of Zambia (SIZ) and Vice Chair for the Zambia

Association of Geographic Information Systems (ZAGIS). Was also Secretary to

an ad hoc committee that recommended amendments to the Land Survey Act.

Research Assistant: Chama, Manda (B.Eng). GIS analyst at the

Mining Sector Development Programme (MSDP) and first ever female Land

Surveyor from the University of Zambia.

Yamikani Mwanza. Geomatic Engineering 2nd year Student, University

of Zambia.

CONTACTS

Department of Geomatic Engineering

School of Engineering

The University of Zambia

P. O. Box 32379

10101 Lusaka

ZAMBIA

Fax + 260 1 29 55 30

Email: armwanza@eng.unza.zm

APPENDICES

|