Article of the Month -

May 2013

|

Revisiting the Interaction between the Nigerian Residential Property

Market and the Macroeconomy

Ismail OJETUNDE, Nigeria

1) This paper is a Nigerian

Peer Review paper, which was presented at FIG Working Week 2013, 6-10

May, in Abuja, Nigeria. Like last month article, this paper highlights

one of the challenges Nigerian surveyors are dealing with, namely the

Nigerian property market. At the conference many papers highlighted the

current challenges Nigerians surveyors are faced with. You can find the

papers

here.

Key words: Macroeconomy, property, property market,

residential, rents.

SUMMARY

The study of residential price dynamics and macro economic

developments are important for virile economic and social policies

formulation at both local and national scales. This paper revisits the

interaction between the Nigerian macroeconomy and the operation of its

residential property market using econometric analysis. By employing a

larger sample and different data analysis approaches (pairwise

correlations, cointegration, granger causality and vector

autoregression) the objective is to provide further evidence on the

extent to which the property market is integrated or linked to

macroeconomy. Evidence suggests that macroeconomic variables (real gross

domestic product, inflation, exchange and interest rates) have long term

relationship with residential property rents in Nigeria. The results of

the granger causality shows that both exchange and interest rates have

useful information for predicting residential property rents over and

above the past values of other macroeconomic variables. Aside, the

result of the variance decomposition within the vector autoregressive

model further confirmed that real GDP and Exchange rate combined

forecast 31.4% of the variance in residential property rents. This study

concludes that the response of the residential property market to

macroeconomic shocks of interest rate, real GDP, and exchange rate

implies a relatively slow adjustment of the property market to the ever

changing macroeconomic events in Nigeria making long run equilibrium

elusive. These findings are significant for the continued development of

the Nigerian property market which is fraught with poor market

information.

1. INTRODUCTION

Residential property is a dynamic commodity characterized by

structural durability, spatial immobility and its physically modifiable

nature. As a consumption and investment commodity, residential property

exerts profound influence on the socio-economic and psychological

well-being of individuals, households and socio-ethnic groups. Since

residential property constitutes the bulk of any country’s tangible

capital, the study of residential price dynamics and macro economic

developments are important for economic and social policies formulation

on both local and national scales. Numerous theoretical and econometric

studies have however investigated the relationship between residential

price (which has remained a significant feature of most markets for

housing services in the world) and the economy (for example, see Barras

and Ferguson, 1985, 1987a & 1987b; Hekman, 1985; Kling and McCue, 1987&

1991; DiPasquale and Wheaton, 1996). Aside investigating the link

between property and the wider economy, a point of convergence in these

previous literature, is the existence of interaction and interdependency

between property and the economy. For instance, during periods of

macroeconomic stability, cycles in property tend to be endogenous

(caused by disequilibria in the sector) and are relatively subdued and

in periods of macroeconomic instability, property cycles tend to be

exogenous (caused by various conditions in the macroeconomy) and

sometimes feature exceptional fluctuations (Dehesh and Pugh, 1995

p.2581). Although this cause and feedback mechanisms described by Dehesh

and Pugh (1995)is a feature of most market based system, the focal point

of this research however is not on endogenous influences, but rather the

nexus between real estate and exogenous influences of the economy.

Earlier studies of this nature provided evidence on the link between

property and the exogenous factors of the economy but have been

considerably skewed to only the United kingdom and United States (McCue

and Kling, 1994; Brooks and Tsolasco, 1999; Ling and Naranjo, 2003) with

both countries having well integrated and transparent property markets.

In developing countries, such evidence is limited to India (Joshi, 2006;

Vishwakarma and French, 2010). In Nigeria, recent study by Ojetunde et

al. (2011) has empirically discountenance the assumption that the

residential property market in Nigeria is not coupled or linked with the

economy. This research revisit the interaction between the economy and

the operation of the residential property market by extending the study

period (between 1984 and 2011) and improving on the data analysis

approaches in Ojetunde et al. (2011) study. Unlike studies in developed

economies which employed data on paper-backed securities, this study

explore the use of nominal rents from direct property investment in the

absence of property returns from the Nigerian Stock Market.

2. THE OPERATION OF THE RESIDENTIAL PROPERTY MARKET AND THE

ECONOMY: A REVIEW

Unlike other highly durable goods, the market for property and by

extension, the operation of residential property presents a somewhat

peculiar complexity as it comprises three (3) independent but connected

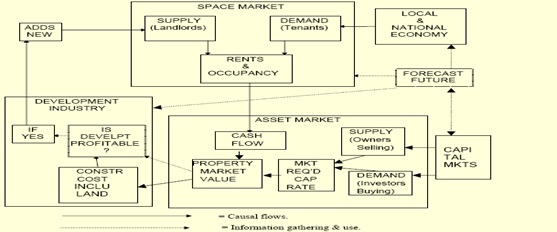

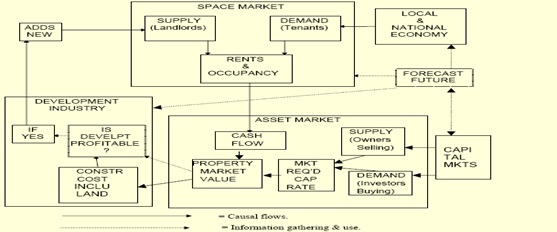

markets linked to the economy. Fig.1 provides for a simple residential

property model and link it with other exogenous systems (local and

national economies and the capital markets). To start with, the model

shows three important components (space, asset and development markets)

which on their own represent market arenas where trade take place and

prices are determined through demand and supply interplay ( Keogh 1994;

Fischer 1999 and Geltner et al., 2007).

The space market involves the interaction of the demand by

residential property users with the current stock of space made

available by the landlords. It is this result of demand-supply

interaction which predicts the pattern of rents and the level of

occupancy with vacancy clearing the market. Within the space market, the

demand for residential space is aptly affected by the national and local

economies. A growth in real wages for example may encourage new

households’ formation and hence an increase in demand for residential

physical space. For instance, property rights can be packaged in the

short run in form of use rights to property users in return for

residential rents (use values).

In the asset market, Viezer, (1999) concludes that the rent

determined in the space market is central in determining the demand for

real estate assets because this cash flow in form of rents interacts

with the cap rates required by investors, with the end product being the

property market/ capital values.

Fig.1: A Model of Residential Property Market: Interaction of the Space,

Asset and the

Development Markets with other Exogenous Systems. Source: Geltner et

al.,(2007).

As such what investors are really buying is the discounted present

value of asset’s expected income flow. The cap rates which investors

require in sealing real estate transactions in the asset market are

affected by opportunity cost of capital (since the desirability of

buying and selling real estate must be considered within a wide spectrum

of other investment opportunities operating within the capital markets),

growth expectation of future rents and investors perception of risk

associated with real estate investment vis-à-vis other investment

outlets in the capital markets (Ling and Archer, 1997b and Geltner et

al., 2007).

On one hand, clear independency however exists between space (use)

and asset markets with respect to right to use space (user rights) as

different from the right to hold a purely financial investment interest

in property (investor rights). On the other hand, connectivity is

evident as the use and investment rights subsisting in a property

ownership (for instance in an unencumbered freehold interest) is

mediated through the development market to meet changing market

requirements of users and investors. It is these market changes in users

and investors requirements which stimulate development activity and

development in turns supplies new user and investors rights into the

market (Keogh, 1994). For example, development would only occur insofar

as property rent can offset the long run marginal cost of a property

(Geltner et al., 2007). It is this singular condition which ensures that

the development market employ physical and financial resources to

construct new built space as well as refurbishment, rehabilitation or

conversion of existing buildings. The role of development therefore

comes to bear in differing ways: An economy in recession needs existing

built space so as to continue to function. Conversely, structural

changes in form of modifying existing dwellings (through refurbishment

and conversion) and new construction of dwellings (resulting from

outward expansion on undeveloped land) is necessary due to economic

growth or structural shifts in the economy.

Aside the foregoing simple property market model, numerous empirical

studies by Barras, (1983); Barras and Ferguson, (1987a, 1987b) and

Barras, (1994) have shown how building boom is triggered through the

combinations of conditions in the real economy, credit economy and

property market. The focal point of these studies is the derivation of a

theoretical framework which has been tested using time-series modelling

techniques to uncover the dynamics and operations within the property

market. Exploring this theme with minor variant, Dehesh and Pugh (1995,

p.2583) have also show considerable evidence that cycles in property has

deep cause-consequence interdependency on the financial and credit

cycles even at a global scale. They further argue that such structural

change resulting from changes in the financial sector requirements may

occur contemporaneously with and interact with the fluctuations in both

the macroeconomy and the credit markets, thereby heightening inflation,

causing financial collapse and leading to recession in the property

sectors.

Previous studies linking property to the economy over time, however,

fall principally into two distinct categories: those that centre

explicitly on property- backed securities such as real estate investment

trusts (Hartzell et al., 1987; Chan et al., 1990; McCue and Kling, 1994;

Brooks and Tsolacos, 1999; Ling and Naranjo, 1997; Ling and Naranjo,

2003) as against those on direct property market variables, as diverse

as construction series and rents ( Kling and McCue, 1987 ; Kling and

McCue, 1991 ; Giussani, et al., 1992). Table 1 summarizes previous

empirical research linking property with the economy. These empirical

investigations are preponderant in the USA with most employing vector

autoregressive framework as their methodology and few using regression

analysis.

Within the first category, Chan et al. (1990) for instance examine

the connection between some pre-specified macroeconomic variables and

real estate returns from the stock market using regression analysis.

They find that changes in risk, unexpected inflation and term structure

are significant predictors; while changes in industrial production and

expected inflation have no significant influence on real estate returns.

McCue and Kling (1994) however extend the examination of the link

between property and the economy in another direction. They treat real

estate returns as a residual by controlling for the covariance between

equity REIT returns and the overall stock market resulting from industry

effects. In their analysis, the authors employ vector autoregressive

model to test the relationships between this real estate residual and

macroeconomic variables and conclude that macroeconomic variables

account for 60% variance in real estate returns.

Brooks and Tsolacos (1999) take a similar approach to McCue and Kling

(1994) study by also removing the impact of the general stock market on

equity REIT series but using UK dataset. They suggest that unexpected

inflation and term structure have a contemporaneous rather than a lagged

effect on property returns. The absence of lagged effect however implies

that changes in unexpected inflation and term structure are quickly

incorporated into property returns. The authors further contend that

property returns are explained by own lagged values: current property

returns may have predictive power for future property returns. They

hypothesise that this own lagged effect is partly due to the fact that

property returns may reflect property market influences (rents, yield

and vacancy rates) rather than macroeconomic variables and partly

because macroeconomic and property data are not in a direct measurable

form.

A departure from the above categorization is the studies by Kling and

McCue (1987) and Kling and McCue (1991) who focus on property market

indicator. They advocate the use of construction series from direct real

estate investment and employ vector autoregressions to model industrial

and office construction cycles. They find that macroeconomic variables

influence real estate series indirectly through other macroeconomic

variables. The authors also show that adjustment to macroeconomic shocks

take place with a lag, resulting from the existence of long production

period between new construction starts and completions.

Giussani et al. (1992) also examine the relationship between changes

in commercial rental values and fluctuations in economy activity using a

predictive model. They analyse monthly data from 1983 to 1991 from

Europe and find that real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the most

significant explanatory variable for rental values. This result is

consistent with those reported in Hetherington (1988) and Keogh (1994)

that GDP is a determinant of rents, to the extent that rents are closely

correlated with the business cycle.

Table 1. Classification of Studies Linking Property with the

Economy.

Author/Year

of Publication |

Study area |

Data type |

*Methodology |

Significant

variables |

| Hoag (1980) |

USA |

Property specific variables, national

and regional economic factors. |

Regression Analysis. |

Property specific variables, national

and regional economic factors. |

| Hartzell et al. (1987) |

USA |

Appraised values from real estate

fund. |

VAR |

Expected and unexpected inflation. |

| Chan et al. (1990) |

USA |

REITs and some pre-specified

macroeconomic variables |

Regression Analysis |

Risk, unexpected inflation and term

structure. |

| Kling and McCue (1991,

1987) |

USA |

Construction series from direct real

estate assets. |

VAR |

Output, nominal interest rates, money

supply and employment.

|

| Giussani, et al. (1992)

|

Europe |

Rental values and macroeconomic

variables. |

Regression Analysis |

GDP |

| McCue and Kling (1994) |

USA |

REITs adjusted for stock influences

and macroeconomic variables. |

VAR |

Nominal interest rates, price, output

and investment. |

| Lizieri and Satchell

(1997a) |

USA |

REITs returns and equity returns

adjusted for property influences. |

VAR |

Lagged values of the equity returns. |

| Lizieri and Satchell

(1997b) |

USA |

REITs returns and real interest rates. |

VAR |

Real interest rates. |

| Ling and Naranjo (1997) |

USA |

REITs returns and macroeconomic

variables. |

VAR |

Term structure, unexpected inflation,

real treasury bill rate and growth in real capital consumption. |

| Brooks and Tsolacos (1999) |

UK |

REITs adjusting for stock influences

and macroeconomic variables |

VAR |

Unexpected inflation, term structure

of interest rate. |

| Ling and Naranjo (2003) |

USA |

Capital flows in present and past

REITs returns and macroeconomic variables |

VAR |

Present and lagged REITs returns. |

| Joshi (2006) |

India |

Housing share prices and interest

rates and credit. |

VAR |

Interest rates and credit growth. |

Vishwakarim

and French (2010) |

India |

REITs and macroeconomic variables. |

VAR |

Term structure of interest rate. |

| Ojetunde, Popoola and

Kemiki (2011) |

Nigeria |

Direct Property returns and

Macroeconomic variables |

VAR |

GDP, Exchange rate, inflation and

interest rates |

By using non- food credit as proxy for housing price in India, Joshi

(2006) employs a structural vector autoregressive model for the period

2001 to 2005 and asserts that both credit growth and interest rate

influence the housing market and stabilize other sectors of the economy.

Vishwakarim and French (2010) also examine the influence of

macroeconomic variables on the India real estate sector between 1996 and

2007. Using a structural break, they conclude that macro economic

variables explain 10% of the variation in the real estate market between

1996 and 2000 with such variation increasing to 23% between 2000 and

2007.

In Nigeria, Ojetunde et al. (2011) estimated a vector autoregressive

model and suggest that macroeconomic shocks explain 28% of the variation

in residential property rents. They further hypothesized that, responses

of residential property rents to shocks in real GDP, exchange rates and

short-term interest rates reflect the fact that rents from direct

residential property and by extension, the market for residential

property adjust slowly to changes in macroeconomic events. Their study

however did not establish the presence of long run equilibrium between

the Nigerian macroeconomy and its property market. This is one of the

focal point of this research.

3. THE DATA

The data were extracted from two distinct sources namely: the

registered Estate Surveying and Valuation firms and the National Bureau

of Statistics (NBS). The aggregation of residential rental price data

was supplied by registered estate surveying and valuationfirms based on

available letting evidence in most parts of Nigeria. National economic

data as varied as Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in real terms, short-term

interest rates, inflation and exchange rateswere provided by National

Bureau of Statistics (NBS). Theirinclusion in the final analysis was

premised on the assumption that trend in real estate returns is

correlated with happenings within the real and credit economy. The

sampledata in annual frequency covers the period 1984 to 2011 with a

total of 28 observations. Table 2 reportsa summary of the descriptive

statistics of the data sample.

Table 2. Summary of Descriptive Statistics of Variables.

| Variable Name |

Description |

Mean |

Std. Dev. |

Min. |

Max. |

| RESDRENT |

Nominal residential property rents

in Nigerian currency (Naira) |

53299 |

61698.53 |

700 |

182022 |

| INFLATN |

Inflation rates (%) |

22.05 |

18.22 |

5.4 |

72.8 |

| EXCHAG |

Exchange rates of Nigerian currency (Naira)to U$1 |

66.45 |

60.75 |

0.7649 |

153.89 |

| INTEREST |

Short term -Interest rates (%) |

18.54 |

4.55 |

9.25 |

29.08 |

| GDP |

Gross Domestic Product

in real terms (expressed in Millions

of Naira) |

446974 |

177712 |

227255 |

885273 |

4. METHODOLOGY

The methodology consists of four different approaches: pairwise

correlation between the variables, Cointegration test, Granger causality

tests(block exogeneity wald tests), and Vector autoregression (VAR).

Cointegration and granger causality tests are within the vector

autoregression framework employed in this research. The pairwise

correlation examines the correlation between the residential rent and

marco economic variables. A vector autoregressive (VAR) framework was

employed for the period 1984 to 2011 in order to investigate the

relationship between residential property market (using RESDRENT as

proxy) and macroeconomic variables (INFLATN, EXCHAG, INTEREST, GDP). A

vector autoregressive model is a systems regression model in which the

variance or current values of the dependent variables can be explained

in terms of the different combinations of their own lagged values and

the lagged values of other variables as well as their uncorrelated error

terms.

The reduced form of the estimated VAR model is expressed as:

Where  =

(RESDRENT, INFLATN, EXCHAG, INTEREST, GDP) is a vector of variables

determined by k lags of all variables in the system, =

(RESDRENT, INFLATN, EXCHAG, INTEREST, GDP) is a vector of variables

determined by k lags of all variables in the system,

is a 5 × 1 vector

of the stochastic error terms (impulses or innovations or shocks), is a 5 × 1 vector

of the stochastic error terms (impulses or innovations or shocks),

is a 5 × 1 vector

of constant term coefficients, is a 5 × 1 vector

of constant term coefficients,

are 5 × 5 matrices

of coefficients on the ithlag of Y, while k represents the number of

lags of each variable in each equation. Equation (1) which is a vector

of 5 variables postulates for instance, that current RESDRENT is related

to its own lag or past values, as well as the lag of the other four

variables (INFLATN, EXCHAG, INTEREST, GDP). In other words, the

information relevant to the prediction of the respective variables is

contained exclusively in the time series data of these variables (Koop,

2000; Diebold, 2001; Gujarati, 2003). Following Lutkepohl (1991)

information criteria technique was used to determine the appropriate

length of the distributed lag. The values of multivariate versions of

the information criteria are constructed for 0, 1,…..k lags (in this

case, a maximum of 2) as seen in table 3 with the objective of choosing

the number of lags that minimise the value of the five information

criteria. are 5 × 5 matrices

of coefficients on the ithlag of Y, while k represents the number of

lags of each variable in each equation. Equation (1) which is a vector

of 5 variables postulates for instance, that current RESDRENT is related

to its own lag or past values, as well as the lag of the other four

variables (INFLATN, EXCHAG, INTEREST, GDP). In other words, the

information relevant to the prediction of the respective variables is

contained exclusively in the time series data of these variables (Koop,

2000; Diebold, 2001; Gujarati, 2003). Following Lutkepohl (1991)

information criteria technique was used to determine the appropriate

length of the distributed lag. The values of multivariate versions of

the information criteria are constructed for 0, 1,…..k lags (in this

case, a maximum of 2) as seen in table 3 with the objective of choosing

the number of lags that minimise the value of the five information

criteria.

Table3. VAR Lag Order Selection Criteria

| Lag |

LogL |

LR |

FPE |

AIC |

SC |

HQ |

| 0 |

-945.6704 |

NA |

3.95e+25 |

73.12850 |

73.37044 |

73.19817 |

| 1 |

-841.9993 |

159.4941* |

9.71e+22 |

67.07687 |

68.52852* |

67.49489 |

| 2 |

-809.6437 |

37.33328 |

7.02e+22* |

66.51106* |

69.17242 |

67.27743* |

*indicates lag order selection by criterion. Where LR denotes:

sequential modified LR test statistic (each test at 5%level); FPE: Final

prediction error; AIC: Akaike information criterion; SC: Schwarz

information criterion and HQ: Hannan-Quinn information criterion. While

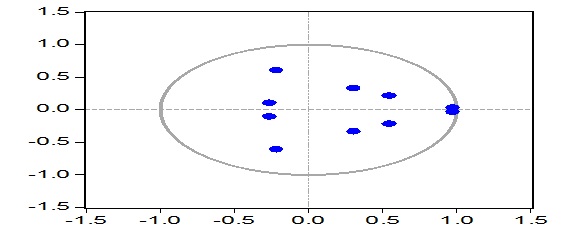

LogL is thelog likelihood function. Analysis of this magnitude presumes

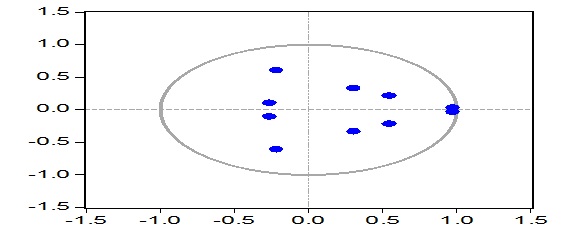

the presence of stationary within the data series(Brooks, 2008).The

examination of the inverse roots of the autoregressive polynomial

(fig.2)however reveals that the absence of non- stationary in all VAR

variables, since none of the roots has a modulus greater than one and

none lies outside the unit circle.

Fig.2: Inverse roots of the Autoregressive Polynomial. Johansen (1988)

cointegration test is applied to the VAR variables to test the

assumption that the five variables are bound by some long run phenomena,

though the variables might deviate from their short run relationship.

The trace and max tests for cointegration under the Johansen approach

show whether the null hypothesis of no cointegration vectors should be

rejected.

Ganger casuality tests were also applied to the estimated VAR

coefficients to determine the critical values of the block exogeneity

wald tests of the null hypothesis, that collectively the coefficients of

all the lags of a particular variable are simultaneously zero. The

rejection of the null hypothesis on the basis of the block exogeneity

tests suggests the variable(s) in the model which impact significantly

on the future values of each of the variables in the system. However,

causality tests only reveal the association among the variables and not

whether variance or change in value of a particular variable has a

positive or negative effect on other variables in the VAR system.

Therefore variance decomposition and impulse response function (IRF)

were estimated to examine the strength of such relationships within the

VAR system.

The estimated variance decomposition of RESDRENT, is the proportion

of the variance in RESDRENT that can be explained by its own shocks and

shocks to other variables. The forecast error variance (S.E) for an four

(4) period forecast horizon within the estimated variance decomposition

determines the proportion of RESDRENT for current and future periods (1,

2,3 and 4) which is accounted for by innovations to INFLATN, EXCHAG,

INTEREST and GDP. It is expected that the total percentage of the

forecast variance due to all innovations for each period sum up to 100.

Impulse response function (IRF) is further generated for the estimated

coefficients matrices in VAR model. The impulse response function traces

out the response of RESDRENT in the VAR system to shocks in the error

terms  in equation

(1) to the extent that, if in equation

(1) to the extent that, if

in the RESDRENT

equation increases by one standard deviation, such change or shock will

change RESDRENT in the current and future periods. in the RESDRENT

equation increases by one standard deviation, such change or shock will

change RESDRENT in the current and future periods.

5. RESULTS

The pairwise correlations in Table 4 show two important results.

First,residential property rents are strongly and positively correlated

with real GDP and exchange rates fluctuations in Nigeria. Secondly,

there are negative but weak correlations between residential property

rents and short–term interest rates as well as between residential

property rents and inflation rates. These results though a working

hypothesis, are later confirmed in the Variance decomposition within the

VAR framework later in this section.

Table 4. Pairwise Correlations of Variables at Zero Lag.

| Pairwise correlations at zero lag |

| |

GDP |

INFLATN |

EXCHAG |

INTEREST |

RESDRENT |

| GDP |

1 |

|

|

|

|

| INFLATN |

-0.31 |

1 |

|

|

|

| EXCHAG |

0.85 |

-0.38 |

1 |

|

|

| INTEREST |

-0.04 |

0.30 |

-0.02 |

1 |

|

| RESDRENT |

0.91 |

-0.34 |

0.91 |

-0.15 |

1 |

The Johansen cointegration test in Table 5shows the eigen value,

statistic, critical value and probability value at 5% level of

significance. By examining the trace test within the first two panels of

the table, null hypothesis of four cointegrating vectors at 5% level is

rejected as the trace statistics are greater than the critical values.

The max test shown in the other panel confirms this result.

On the basis of the granger causality test, it can be seen that with

the exception of inflation other macro economic variables forecast

RESDRENT. In this case all the lag coefficients of each of the

macroeconomic variables are statistically significant (p-values are less

than 5%) in the residential property rent equation, as indicated in the

last panel of table 6.

As a corollary, granger causality tests also show that while both the

short -term interest rates and exchange rates have significant effects

in the residential property rents, there is evidently ‘no reverse

significant’ of residential property rents on these two macroeconomic

variables ( their P Value are 0.2677 and 0.2838 respectively). These

results suggest that these two macroeconomic variables (short-term

interest rate and exchange rate) ‘granger cause’ residential property

rents and that these two macroeconomic variables have useful information

for predicting residential property rents over and above the past values

of other macroeconomic variables in the VAR model.

Table 5: Johansen Cointegration test for VAR Varaibles between 1984 -

2011

Unrestricted Cointegration Rank Test (Trace)

|

| Hypothesized |

|

Trace |

0.05 |

|

No. of CE(s)

|

Eigenvalue

|

Statistic |

Critical Value |

Prob.** |

| None * |

0.907094 |

134.6947 |

69.81889 |

0.0000 |

| At most 1 * |

0.706700 |

75.29040 |

47.85613 |

0.0000 |

| At most 2 * |

0.622274 |

44.62641 |

29.79707 |

0.0005 |

| At most 3 * |

0.527889 |

20.28673 |

15.49471 |

0.0088 |

At most 4

|

0.059109

|

1.523204

|

3.841466

|

0.2171

|

| Trace test indicates 4 cointegrating eqn(s) at

the 0.05 level |

| * denotes rejection of the hypothesis at the

0.05 level |

**MacKinnon-Haug-Michelis (1999) p-values

|

Unrestricted Cointegration Rank Test (Maximum

Eigenvalue)

|

| Hypothesized |

|

Max-Eigen |

0.05 |

|

| No. of CE(s) |

Eigenvalue

|

Statistic |

Critical Value |

Prob.** |

| None * |

0.907094 |

59.40431 |

33.87687 |

0.0000 |

| At most 1 * |

0.706700 |

30.66399 |

27.58434 |

0.0195 |

| At most 2 * |

0.622274 |

24.33968 |

21.13162 |

0.0171 |

| At most 3 * |

0.527889 |

18.76353 |

14.26460 |

0.0091 |

At most 4

|

0.059109

|

1.523204

|

3.841466

|

0.2171

|

| Max-eigenvalue test indicates 4 cointegrating

eqn(s) at the 0.05 level |

| * denotes rejection of the hypothesis at the

0.05 level |

| **MacKinnon-Haug-Michelis (1999) p-values |

Table 6: Granger Causality/ Block Exegeneity Wald Tests

Dependent variable: EXCHAG

|

| Excluded |

Chi-sq |

df |

Prob. |

| GDP |

2.372984 |

2 |

0.3053 |

| INFLATN |

1.762238 |

2 |

0.4143 |

| INTEREST |

1.794556 |

2 |

0.4077 |

RESDRENT

|

2.518923

|

2

|

0.2838

|

All

|

6.178470

|

8

|

0.6272

|

Dependent variable: GDP

|

| Excluded |

Chi-sq |

df |

Prob. |

| GDP |

0.733207 |

2 |

0.6931 |

| INFLATN |

0.440865 |

2 |

0.8022 |

| INTEREST |

2.984277 |

2 |

0.2249 |

RESDRENT

|

8.576370

|

2

|

0.0137

|

All

|

17.26949

|

8

|

0.0274

|

Dependent variable: INFLATN

|

| Excluded |

Chi-sq |

df |

Prob. |

| GDP |

0.365033 |

2 |

0.8332 |

| INFLATN |

0.603316 |

2 |

0.7396 |

| INTEREST |

0.674100 |

2 |

0.7139 |

RESDRENT

|

0.162122

|

2

|

0.9221 |

All

|

4.899009

|

8

|

0.7683

|

Dependent variable: INTEREST

|

| Excluded |

Chi-sq |

df |

Prob. |

| GDP |

0.835167 |

2 |

0.6586 |

| INFLATN |

2.085102 |

2 |

0.3526 |

| INTEREST |

9.443655 |

2 |

0.0089 |

RESDRENT

|

2.635744

|

2

|

0.2677

|

All

|

16.15057

|

8

|

0.0403

|

| Dependent variable: RESDRENT |

| Excluded |

Chi-sq |

df |

Prob. |

| GDP |

8.923314 |

2 |

0.0115 |

| INFLATN |

33.35944 |

2 |

0.0000 |

| INTEREST |

3.570942 |

2 |

0.1677 |

RESDRENT

|

10.34877 |

2

|

0.0057

|

All

|

46.27143

|

8

|

0.0000

|

Again, residential property rents and real GDP which are both

significant imply the existence of feedback relationship between real

GDP and residential property rents. The variance decomposition of

residential rents to shocks or innovations in macroeconomic variables in

Table 7 further confirms this result as it shows the contribution of

each macroeconomic shock to residential property rents.

Table 7: Variance Decompositions for Residential Property Rent

|

Period |

FORECAST ERROR VARIANCE (S.E) |

EXCHAG |

GDP |

INFLATN |

INTEREST |

RESDRENT |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

15.19901 |

0.000000 |

0.000000 |

0.000000 |

0.000000 |

100.0000 |

| 2 |

22.19551 |

6.951051 |

18.91081 |

0.023707 |

0.001505 |

74.11293 |

| 3 |

28.63879 |

9.285895 |

18.61029 |

0.087174 |

0.205616 |

71.81102 |

| 4 |

34.27057 |

14.10323 |

17.31054 |

0.485487 |

0.360693 |

67.74005 |

Cholesky ordering: RESDRENT INFLATN EXCHAG INTEREST GDP.

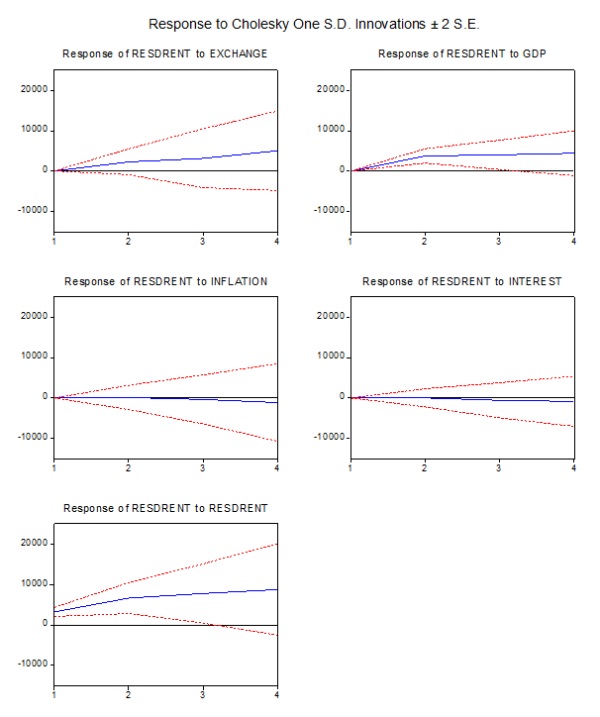

The forecast error variance (S.E) for four (4) years shows that real

GPD and Exchange ratetogether forecast 31.4% of the variance in

residential property rents. This result is consistent with those

reported in earlier studies byKeogh (1994) that GDP predicts the pattern

of rents and the findings of McCue and Kling, (1987); Kling and McCue,

(1994) that short- term interest rates contributes to the variation in

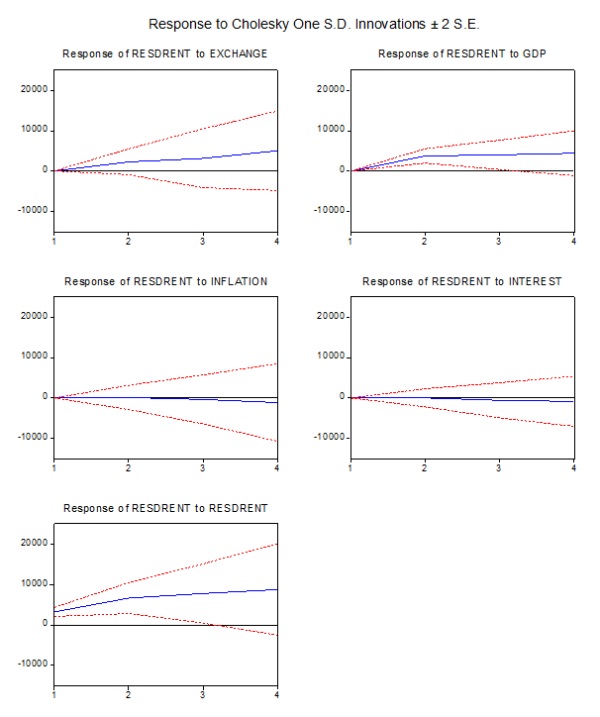

property returns performance. Finally, the Impulse Response Function

(IRF) as depicted in fig. 3shows that shocks to short-term interest

rates have a negative significant impact on residential property rents,

with the shocks getting a bit pronounced afterperiod two. Shocks or

innovations in inflation is negative but not significant and the shocks

die away instantly even at year zero. Increase in real GDP and exchange

rates have significant positive effects on residential rents. In this

case, rents appear to settle down quickly to a steady rising state after

period onedue to shocks of exchange rate and in the second period year

to shocks of real GDP.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Revisiting the interaction between the Nigerian property market and

the macroeconomy has further confirmed that the use of econometric

analysis rather adhoc methodologies purged with simple trend

interpolations is plausible. Since residential property rent is a

significant feature of most property market in the world, empirical

evidence based on this study from Nigeria implies that exogenous

influences of the economy (real GDP and Exchange rate) account for 31.4%

of the variation within the residential property market. At a

disaggregate level, real GDP accounts for a substantial proportion

(17.3%) of this variation in the residential property market, while

exchange rate account for the remaining 14.1% of these residential

property market variance. In addition the feedback mechanism between GDP

and residential property rents, means that these two variables are

determined contemporaneously and by implication depicts a somewhat

limited integration of the Nigerian residential property market with the

economy. The one to two period(s) response shocks of interest rate, real

GDP, and exchange rate show a relatively slow adjustment of the market

to the ever changing macroeconomic events in Nigeria. Such responses are

exogenous and make long run equilibrium within the residential property

market almost elusive. The existence of such analysis of this nature

will in the end aid useful property market analysis in a market fraught

with poor property market data.

Fig.3. Responses of Residential Property Rent to Shocks in

MacroeconomicVariables.

REFERENCES

Barras, R. (1983). A simple theoretical model of the office

development cycle. Environment and Planning A, 15, pp.1381-1394.

Barras, R. (1994). Property and the economic cycle: building cycles

revisited. Journal of

Property Research, 11, pp. 183–197.

Barras, R., and Ferguson, D. (1985). A spectral analysis of building

cycles in Britain. Environment and Planning A, 17, pp.1369-1391.

Barras, R., and Ferguson, D. (1987a). Dynamic modelling of the building

cycle 1: theoretical framework. Environment and Planning A, 19, pp.

353–367

Barras, R., and Ferguson, D. (1987b). Dynamic modelling of the building

cycle 2: empirical

results. Environment and Planning A, 19, pp. 493–520.

Brooks, C. (2008). Introductory econometrics for finance. 2nd ed. New

York: Cambridge University Press.

Brooks, C., and Tsolacos, S. (1999). The impact of economic and

financial factors on UK property performance. Journal of Property

Research, 16(2), pp. 139–152.

Chan, K.C., Hendershott, P.H. & Sanders, A.B. (1990). Risk and return on

real estate:

evidence from equity REITs. American Real Estate and Urban Economics

Association Journal, 18, pp. 431-452.

Dehesh, A., and Pugh, C. (1995). Property cycle in a global economy.

Urban studies, 37(13)

pp.2581-2602.

Diebold, F.X. (2001). Elements of forecasting. 2nd ed. South Western

Publishing.

DiPasquale, D., and Wheaton, W.C. (1996). Urban economics and real

estate markets. New-

Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc. Englewood Cliffs.

Geltner, D. M., Miller, N. G., Clayton, J. & Eichholtz, P. (2007),

Commercial real estate

analysis and investments, 2nd ed.Thomson South-Western.

Giussani, B., Hsai, M. & Tsolacos, S. (1992). A comparative analysis of

the major determinants of office rental values in Europe.Journal of

Property Valuation and Investment, 11(2), pp.157–173.

Gujarati, D. N. (2003). Basic econometrics. 4th ed. New York:

McGraw-Hill

Hartzell, D., Hekman, J.S. & Miles, M.E. (1987). Real estate returns and

inflation. American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association Journal,

15(1), pp. 617-637.

Hekman, J.S. (1985). Rental price adjustment and investment in the

office market. American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association

Journal, 13(1), pp. 32-47.

Hetherington, J.T. (1988). Forecasting of rents. In: A. MacLeary and N.

Nathakumaran,

eds.Property investment theory, UK: Spon.

Hoag, J.W. (1980). Towards indices of real estate value and return.

Journal of Finance, 35(2), pp 569-580.

Johansen, S. (1988). Statistical analysis of cointegrating vectors.

Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 12, pp. 231-254

Joshi, H. (2006). Identifying asset price bubbles in the housing market

in India- preliminary evidence. Reserve Bank of India Occasional Papers

27, pp. 73–88.

Keogh,G. (1994). Use and investment markets in British real estate.

Journal of Property Valuation and Investment, 12(4), pp 58-72.

Kling, J.L., and McCue, T.E. (1987). Office building investment and the

macroeconomy: empirical evidence, 1973-1985. American Real Estate and

Urban Economics Association Journal, 15(3), pp.234-255.

Kling, J.L., and McCue, T.E. (1991). Stylized facts about industrial

property construction. Journal of Real Estate Research, 6(3),

pp.293-304.

Koop, G. (2000). Analysis of economic data. New York: John Wiley and

Sons.

Ling, D., and Naranjo, A. (1997). Economic risk factors and commercial

real estate returns, Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics,

14(3), pp. 283-307.

Ling, D., and Naranjo, A. (2003). The dynamics of REIT capital flows and

returns, Real Estate Economics, 31, pp. 405–434.

Lizieri, C., and Satchell, S. (1997a) Interactions between property and

equity markets: an investigation of linkages in the UK 1972-1992.

Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 15(1), pp.11-26.

Lizieri, C., and Satchell, S. (1997b) Property company performance and

real interest rates: a regime switching approach. Journal of Property

Research, 15, pp. 85-97.

Lutkepoh, H. (1991)Introduction to Multiple Time Series Analysis, New

York: Springer-Verlag.

McCue, T.E., and Kling, J.L. (1994) Real estate returns and the

macroeconomy: some

empirical evidence from real estate investment trust data, 1972-1991,

Journal of Real

Estate Research 9(3), pp. 277-287.

Ojetunde, I., Popoola, N.I., and Kemiki, O.A. (2011). On the interaction

between the Nigerian residential property market and the macroecconomy.

Journal of Geography,Environment and Planning, 7(2), University of

Adoekiti, Nigeria.

Stiglitz, J. (1994). The role of the state in financial markets. In: M.

Bruno and R. Pleskovic, eds. Proceedings of the World Bank Annual

Conference on Development Economics 1993, pp. 19–56. Washington, DC:

World Bank.

Viezer, T.W.(1999). Econometric integration of real estate’s space and

capital markets. Journal of Real Estate Research, 18(3).

Vishwakarma, V.K., and French, J.J. (2010). Dynamic linkages among

macroeconomic factors and returns on the Indian real estate sector.

International Research Journal of Finance and Economics, 43.

CONTACT

Ismail Ojetunde

Federal University of Technology, Minna. Nigeria

P. M. B. 65 Minna, Niger State of Nigeria

Minna

NIGERIA

Tel: + 2347033780000

Email:

i.ojetunde@futminna.edu.ng,

ismajet2003@yahoo.com

|