Article of the Month -

March 2012

|

Informal Development in Greece: New Legislation for Formalization, the

Chances for Legalization and the Dead Capital

Chryssy POTSIOU and Ifigenie BOULAKA, Greece

1) FIG-Vice President Chryssy

Potsiou is beside other responsibilities leading the new Task

Force (TF) on “Property and Housing” which is very relevant

in these turbulent times. The TF will have two special sessions during

the Working Week in Rome, May 2012. In this peer-reviewed paper the

authors present the results of a recent scientific research on the

problem of informal development in Greece and explain the new

legislation for formalization of those informal constructions, that are

built on legally owned land in the planned and the non-planned areas;

the existing informalities refer only to planning and building

regulations.

Key words: Informal Settlements, Dead Capital, Property

Taxation, Valuation, Legalization Tools, Property Formalization

SUMMARY

This paper presents the new findings of a focused research made by

the authors at the National Technical University of Athens on the

problem of informal development in Greece, on the newly adopted legal

tools used for formalization and on the existing loss of revenue due to

the informal construction in the non-planned areas. More specifically,

this paper presents the new legislation for formalization of those

informal constructions, that are build on legally owned land in the

planned and the non-planned areas; the existing informalities refer only

to planning and building regulations. The legislation was adopted by the

Greek Parliament, in 2010 and 2011. The legislation for the

formalization project, the first statistics and the reactions of those

involved is briefly described, analyzed and criticized. In addition,

this paper presents the first results of a study focused on the rough

estimation of the economic impact of the informal development in Greece;

starting with the estimation of the capital that is locked in the

informal constructions in the non-planned areas that by existing

legislation is not taxed, and cannot be legally transferred, inherited,

rented and mortgaged, which according to Hernando de Soto’s theory is

considered to be a “dead capital”.

The methodology followed for this research includes literature

research of previous publications on informal development in Greece and

existing and new legislation; interviews with property owners of

informal constructions and the local authorities in the various

municipalities and informal communities in Attika, the greater region of

Athens, the local real estate agents, the local constructors involved in

informal and/or semi-legal construction, the Greek experts (civil

engineers, planners, surveyors, etc), and the potential buyers in the

new situation established by the newly applied formalization project;

and a case study for the estimation of the dead capital in an area with

informal development in Attika, on-site visits, field and office work.

First a brief investigation of the current situation of the informal

development in Greece is given; a summary of the recent government’s

activity in this field is made and the new legislation for formalization

of informal properties for a 30-year period is reviewed. Then, the dead

capital locked in informal development in a community in Keratea, a

suburb in the greater region of Athens, is thoroughly investigated and a

rough estimation of the total dead capital locked in informal

development is attempted. Some thoughts and proposals for future

improvements follow.

1. INFORMAL DEVELOPMENT IN GREECE

Much of the research on informal development in Greece compiled until

2009 is already wrapped up in the 2010 FIG/UN HABITAT/GLTN/TEE

publication on “Informal Development in Europe. Experiences from Albania

and Greece” (Potsiou, 2010; Augustinus & Potsiou, 2011). An up-dated

description of the state-of-the-art of informal development in Greece

and the legal actions taken until now follows below.

For several years Greece has been dealing with poverty, immigration,

inefficient land administration and planning, and has experienced

several “generations” of informal or unplanned development. Emphasis has

been given to providing education for land professionals and on raising

awareness at all levels about the importance of securing and protecting

public and state-owned land (Potsiou & Basiouka, 2010), safeguarding the

environment and cultural heritage and acceptance of a tax system on real

estate private property. Civil engineering standards are enforced in

construction due to the high risk of earthquakes. Due to a continuous

effort to provide social services to the poor (Potsiou & Dimopoulou,

2011) there are very few slums and the majority of buildings are safe

and strong, built on legally owned land.

The major cause of informal development in Greece is the inefficiency

of the planning system and the over regularization of land.

Informalities in Greece are mainly related to an excess of zoning,

planning and building regulations, or construction without permission,

and not to squatting or a lack of ownership rights (Potsiou &

Dimitriadi, 2008; Tsenkova et al, 2009). Informal development mainly

includes construction of 1-2 storey single family houses, build without

building permits, in unplanned areas (Potsiou & Ioannidis, 2006), or 1-2

room extensions beyond legal constructions. Approximately one fifth (or

more than 1,000,000) of the constructions are informal build in small

parcels without a building permit, not including those built with a

permit but with slight informalities, like building-up in semi-open

spaces, change of uses, extra rooms in excess of the building permit

(Dimopoulou & Zentelis, 2007).

As detailed planning process is too expensive and slow, basic

infrastructure such as fresh water, electricity, telecommunication and

roads, have been provided in many areas without a detailed city plan

because local authorities try to upgrade the neighbourhoods

periodically. Greek people resort to informal construction when there is

no other realistic and affordable choice available that satisfies their

needs. A 2009 opinion pole, commissioned by the Technical Chamber of

Greece for the purposes of the FIG/UN HABITAT/GLTN/TEE 2010 study on

Informal Development in Europe-Experiences from Albania and Greece,

shows that 40% of respondents have difficulties in paying their housing

loans. About 50% of Greeks polled consider informal development on their

legally owned land as the only solution to their housing needs. It

should be noticed here that these figures refer mainly to the situation

as it was before the current economic crisis in Greece, which had only

started in October 2009.

Planning principles in Greece are not keeping up with national and

international social and economic changes. The existing spatial and

urban planning legislation is comprehensive but very complex (over

25,000 pages of legislation), focusing on the control of development and

protection of the environment and the public lands. This is not easily

interpreted either by professionals, or by citizens. Urban planning is

centralised and expensive. Detailed city planning studies at an average

take more than 15 years and cost higher than 6,000 € per hectare. In an

effort to facilitate market demand for housing, construction was allowed

in the non-planned areas, but obtaining building permits requires

involvement of more than 25 land related agencies, may take several

years, and in many cases requires court decisions (Potsiou & Dimitriadi,

2008). The planning process runs at a different speed to market needs

and cannot accommodate short term needs when there are large demands.

Planning criteria usually do not include local market interests. Certain

parameters make planning a complicated, expensive and time-consuming

task, such as the lack of necessary spatial data infrastructure (e.g.

cadastral maps, forest maps) and the fact that the areas under planning

already include formal or informal developments. Planned towns are

constrained and have limited space for further development. For that

reason real estate values are extremely high for condominiums in the

planned areas (even within blue collar areas) while salaries remain low.

The Greek Constitution gives priority to environmental and social

issues, rather than economic development needs (Potsiou & Basiouka,

2010). More than 50% of the country is protected land without any

compensation, ignoring the existing legal private property rights and

the damage such regulations cause to the private properties. However,

the state cannot respond well with its resources for management. This

policy restricts serious investment and impacts the economic development

of the country. The statutory environmental constraints are not clearly

defined and not delineated on maps. There are current nation-wide

projects to compile cadastral maps, forests and forest lands maps and

define the public coastal zone. These are expected to uncover long

existing problems in private properties and provide the tools for sound

decisions about major necessary reforms. Upon completion of such maps,

the state may claim property rights on “protected” areas, although

private interests have claimed registered ownership for several years.

Already, the first statistical data derived from the cadastral surveys

show that approximately 45% of the properties in the unplanned areas

recorded in the system is claimed by the state. Existing environmental

legislation creates a huge overlap between private and state rights, as

the state claims ownership over whatever parcel is characterized as

forest. This is a major reason for delays on urbanization projects.

By Constitution, informal construction cannot be legalized in Greece

if built in non-planned but protected areas (e.g. forest lands, coastal

zones, archaeological sites), or if it violates existing planning or

building regulations in the planned areas. Individual informal

constructions in highly protected areas that create serious damage are

demolished after court decisions. Strong laws and high penalties for

environmental protection are applied. This has significantly reduced the

environmental impact of informal development, especially in the coastal

zones, archaeological sites and forests of today. However, there are

still informal settlements with weak, disputed ownership rights within

areas that are forests and many in areas that are not forests today but

used to be forests some many decades ago; unfortunately there are no

statistics on that.

Few forest maps in the Attika region (where the problem seams to be

more significant) are already published and citizens are asked to submit

their objections in case their legally owned parcel is characterized as

“forest”; in such cases, according to the law the parts of the forest

maps that will not be disputed by citizens will be ratified as forest

areas meaning that according to existing legislation the state will then

become the land-owner of these areas. However, citizens are asked to pay

high fees in order to submit objections; unfortunately many Greek

politicians have mislead the Greek citizens by assuring them that there

is no need to spend money and submit objections on the published forest

maps assuring them that these maps will never be ratified.

All penalties derived from informal development are deposited to the

Special Fund for Implementation of Zoning and Urban Plans. This fund is

under the authority of the relevant Minister for the Environment, Energy

and Climate Change to decide how these funds will be used. That way the

revenue generated by penalties, which is considerable, is frequently

channelled directly to central government and not to local government.

This creates public mistrust. There would be more incentive for local

government agencies to resolve informal developments through new urban

plans if they benefited financially.

The only possibility for legalization of informal settlements in the

non-planned areas is through an enforcement of a city plan, if permitted

by the Constitution, improvement of infrastructure, and individual

inspection regarding safety controls. During the last decade hardly any

new plans were ratified though. Until legalization, such informal

constructions cannot be mortgaged, inherited, sold or rented formally,

even though owners have legal rights on the land parcels and they pay

property taxes.

2. THE ODYSSEY OF FORMALIZATION

This chapter investigates and comments on the new legal framework

adopted since 2009, that aims to “formalize planning informalities and

exceeds of building permits in the planned and non-planned areas for a

certain period of time”. The interviews made for this research are also

investigated here and have shown that unfortunately all people that have

been interviewed believe that until today there is no clear will and

concrete strategy or any published action plan on how the Greek

politicians will solve the informal settlement problems that have

accumulated and surface during the compilation of the Hellenic Cadastre

project and the forest maps threatening the success and sustainability

of these projects. Instead, only ad hoc legislation is adopted according

to the short-term specific political preferences each time and/or under

the pressure of the current economic crisis and the need to collect

money. Some examples, together with the results of the interviews with

(a) owners or occupants of informal constructions, (b) local

authorities, (c) involved experts, (d) local professionals like

constructors and estate agents and (e) interested buyers are

investigated and presented below.

2.1 New Legislation for formalization of planning and building

informalities

In 2008 the government started investigating procedures to legalize

planning and building violations that exist in the planned areas (like

the build-up on semi-open areas of the buildings). In September 2009 a

new law was adopted to serve this purpose which however aimed to

legalize only the informalities that exist within the ratified legal

outline of the volume of the building (Figure 1 right). This means that

any exceeds in the height of the building (Figure 1 left) or

constructions that exceed the legal horizontal coverage could not be

legalized by this law. By this law, legalization act was considered to

be permanent and was supposed to end up with a new property title in

which the correct area size of the property would be written. By

tradition, the political opposition claimed that this law is against the

Greek Constitution, as by legalizing the extra built-up area there would

be an increase of the area/floor ratio and thus an increase of the urban

density of the city and according to the existing Greek case law any

increase of urban density is supposed to have a negative impact on the

environment and is not permitted according to the Greek Constitution.

Figure 1. Illegal room under the roof of the building (left);

build-up semi-open areas within the ratified outline of the volume of

the building (right). Source: (Dimopoulou et al, 2007)

However, this old fashioned approach in Greece is against the current

global strategies for the adaptation and mitigation measures for climate

change and environmental protection, which mainly encourage an increase

of urban densities; e.g., “we need to take immediate actions to make

our cities more sustainable by revising our land-use plans, our

transport modalities, and our building designs… to reduce traffic

congestion, improve air and water quality, and reduce our ecological

footprint. In that respect urban density is a key factor … because less

energy is needed to heat, light, cool and fuel buildings in a compact

city where most of the population commutes by public transit” (El

Sioufi, 2010).

In October 2009 after the national elections, simultaneously with the

beginning of the economic crisis in Greece, Law 3843/2010 was prepared

by the new government and adopted by the Greek parliament with the

purpose to formalize only for a period of 40 years (not legalize), the

violations that exist within the ratified outline of the volume of the

building (Figure 1 right). By Law 3843/2010 the “Special Fund for

Implementation of Zoning and Urban Plans” was renamed into “Green Fund”

and the revenue of this fund was planned to be used for environmental

and regeneration projects.

During 2010 and until September 2011 declaration submission of the

above informalities was in fact optional and practically meaningless for

the owners, as transactions and mortgages of properties in the planned

areas with such minor informalities have been always permitted as there

was no specific relevant legal binding instrument in place.

Figure 2. Informalities in the planned areas that do not exist

within the ratified outline of the volume of the building, but can be

formalized by Law 4014/2011

In September 2011, under the pressure of the economic crisis, Law

4014/2011 was adopted by the Greek parliament. The Law was supported by

the majority of the members of the parliament of the two largest

political parties. By this law, in an effort to make the submission of

declaration of informalities within the planned areas obligatory

government has decided that for any future property transaction (formal

or informal) a declaration of the owner and a recent certificate signed

by a private engineer after a recent on site inspection is required

certifying that there is no informality in the real estate at the time

of transaction (before any transaction the property owner must hire a

private engineer to check the real situation of the construction with

the permit in case of informalities and certify compliance. This on-site

control must be done each the real property is transferred).

This measure is well accepted by the engineers however it means that

transaction costs for any property are increased significantly

regardless whether the property is legal or not, as the certificate is

necessary anyway before any transaction, and generally the transaction

procedure is becoming even more bureaucratic. This is against the global

strategies for the economy and the real estate markets that require a

reduction of the required time and costs for the property transactions

(World Bank, 2011). Recently, the relevant Minister has clarified that

this certificate is not required in case of mortgages.

Law 4014/2011 also allows the formalization of planning and building

informalities, only for a period of 30 years, of constructions which

exist either within the planned areas (but are not within the volume of

the building (Figure 1 left, Figure 2) or within the non-planned areas

and lie on legally owned parcels (Figure 3) that are not within the

“protected areas”. Within the 30 year period that those properties will

be formalized in the non-planned areas, local authorities are expected

to proceed with the compilation and implementation of the necessary city

plans, otherwise owners of such properties will be asked to pay

extremely high penalties in order to “buy” the necessary land and

formalize again. For the region of Attika, for example, in order to

build legally in the non-planned areas one needs a parcel of area size

at least 2 ha, while the average parcel where such informal properties

are build is 300-500 m2.

According to this law, for the next 30 years owners of these

properties will not be asked to pay any additional formalization

penalties for the illegalities that will declare now; connections with

utilities will be provided (to those few that are still denied); and

transactions will be permitted when the owner will pay all legalization

fees in advance and receive the relevant certificate of formalization.

Formalization fees are high but scalable depending on the year of

construction, the zone value, and whether the property serves as first

residence or not, and can be paid in instalments within the next 2.5

years. However, owners must hire engineers for the preparation of the

necessary plans and documents (surveyors should prepare high accuracy

surveying plans and civil engineers should inspect the construction’s

stability and submit a standardized form).

Figure 3. Informal settlements in the non-planned areas in

Keratea, Greece

Due to the crisis, by a revision of the draft law, 95% of the revenue

of the “Green Fund” (such as the revenue derived from the formalization

fees of build-up on semi-open areas, the informal buildings, the trade

of emission rights and the environmental penalties) will be directed to

the regular national budget.

Within the next 30 years if the municipalities will prepare detailed

city plans these informal settlements will be finally legalized. The

unfortunate situation in Greece is that this new legislation is not

accompanied with a reform of the planning system and procedures. Thus,

both Law 3843/2010 and Law 4014/2011 have inherited the weaknesses of

the Greek planning system (in terms e.g., complexity, confusion,

bureaucracy) and instead of solving the problem in the informal areas

new costs, mistrust and bureaucracy are added, the problem is simply

postponed for 30 years with an uncertain future.

In addition formalization procedure is insecure, costly and long and

with the current economic situation the success of this formalization

project is questionable.

2.2. First statistics, public opinion and concerns

Investigation of the first statistics and the opinions of those

involved in the project is of significant interest. There are

approximately 1.5 million small informalities in total within the

planned areas; until recently only 655,000 declarations have been

submitted for formalization according to Law 3843/2010. According to the

Ministry, most declarations have been submitted in Athens, Eastern

Attika, Thessaloniki, Creta, Evia, islands of Dodecanese, and Cyclades.

The formalization fees for this project are estimated to be 5-11% of the

tax value. The revenue until today is approximately 190 million €, while

the originally expected revenue from formalization of the build-up on

semi-open areas of the buildings was 800 million €.

Interviewed owners of properties that belong to the above category

feel that they are forced to pay large amounts of money for

formalization fees on top of all the other taxes the government enforces

on real properties; they are willing to participate but unable to pay;

the situation becomes absolutely unrealistic especially when existing

housing loans, all new taxes and formalization fees must be paid

simultaneously, within the same year.

The government extended the deadline for declaration submissions for

one more month hoping to collect more declarations and formalization

fees.

Formalization by Law 4014/2011 has started in September 2011 and is

supposed to finish by the end of November 2011. This law refers to more

than one million buildings mainly located in the non-planned areas all

over Greece. However, by the end of October 2011 only 30,000

declarations have been submitted, which so far has brought revenue of

only 6 million €. Greek government had announced a very optimistic

estimation that this formalization project would bring about 600-700

million € revenue by the end of 2011. A rough analysis of the declared

informal buildings shows that the majority of those declared are

commercial constructions and a few expensive informal residences. This

proves that so far only the wealthy owners declare their informal

properties. However, the majority of the Greek owners of informal

buildings cannot afford to pay fees due to severe salary reductions,

increased prices, and increased income and property taxes. Many wonder

what will then happen to the middle and low income owners of such

informal houses who cannot afford to pay? What will happen to those

informal settlements that exist on land claimed by the state? What will

happen to the vulnerable groups, like some Roma (Potsiou et al, 2011),

and to some minority who do not even have formal legal rights on land?

This legislation does not have an inclusive character.

In addition, the governmental decision that directs 95% of the

revenue of the “Green Fund” to the regular national budget instead of

using this revenue to fund environmental improvements introduced a new

high risk to the formalization project. According to the Greek case law

this could be against the Greek Constitution and the whole project maybe

locked at the Greek courts. Owners are aware of that risk; they

understand that even if they declare the informality and even if they

pay the formalization fees they may still be unable to formalize the

property. It is obvious that even if everything goes well they will be

scared to invest and improve these properties for the next 30 years.

However, the responsible Minister of Environment, Energy and Climate

Change has tried to comfort people by ensuring them that “the Council

of the State (Highest Court) understands the priorities of the country”.

Interviews with local authorities in areas with informal development

gave positive results; local authorities have long been struggling to

upgrade the informal settlements and integrate them into the city plans;

however, it is unclear how they will manage to find the necessary funds

for the necessary future planning. Planning procedures need to be

revised and property taxation revenue should be directed to local

authorities to enable them to meet the needs.

Involved experts like engineers are supportive as this project

creates new jobs for them. Much of the responsibility for the

implementation of planning rules and regulations is now transferred to

the private engineers. Engineers are asked to make a visual quality

evaluation of the construction and to fill out and sign a standardized

form about the stability of the building. The educational centre of the

Technical Chamber of Greece has organized e-training courses to improve

the engineers’ professional capacity in this field and to emphasize the

importance of the professional ethics. The Ethic Code for engineers is

reminded to those involved in this project; as the Ethic Code now

replaces the state supervision and operates like a social contract

between the individual professionals, the professional unions, the

clients and the society the TCG is currently working on the Code’s

revision. Engineers are asked to avoid unethical or unfair competition;

they are reminded that any abuse of a dominant position is prohibited;

they must inform the owners in a simple and understandable language; and

they should also publish and share their knowledge and experience in

order to improve the general capacity of the professional body.

Other local professionals like constructors and real estate agents

have been interviewed, too. Most of the local constructors have been

informally acting as real estate agents as well; the majority of them

are against the formalization law; they are anxious to sell the

semi-legal constructions they have under construction as fast as

possible fearing a price decrease. As construction is long restricted in

the non-planned areas and informal houses can not be legally

transferred, so far the semi-legal constructions they manage to build

are not too many and they are very expensive and profitable. Probably,

through formalization a great number of properties are expected to be

available in the formal market, which will increase the supply and the

prices are expected to fall.

In general real estate market is heavily affected by the economic

crisis in Greece. Local real estate agents informed that the market in

informal areas is practically frozen since 30 years ago and in cases

there was a sporadic transaction owners were in need and were always

prepared to sell less than half of the “real value”. With Greeks facing

the economic crisis today only foreigners may be possible buyers in the

Greek real estate market; this is happening in the areas close to the

sea.

Finally, it was interesting to hear the view of some foreigners,

potential buyers interested in buying single houses in the suburban

coastal areas in Greece. In such areas a number of informal vacation

houses exist, which by the formalization will be available for sale. The

high formalization fees and the 30 years formalization duration is

considered to be a great weakness though.

Their views can be summarized in the following statement made by a

well informed foreigner for the purposes of this research: “The sale

of "protection" services has a long history in the major cities in the

United States. A store or restaurant owner is approached by the

neighbourhood boss of thugs and advised that without his protection the

security of the enterprise cannot be guaranteed. Doubt on the part of

the store-owner is dissuaded when his windows are blown out the next

day. Protection will cost the proprietor a percentage of his gross (not

net) income. It is extortion in its simplest form. Accordingly, I was

astonished to read of the proposal of the Greek government to charge

certain homeowners a fee (tax? penalty?) for protection against the

demolishment of their houses for the next 30 years. It is extortion of a

higher order.

The condition of "informal development", i.e., the construction of

buildings without building permits, or construction in otherwise banned

areas such as a forest or coastal zone, is a recognized problem in

Greece, the Balkans, Eastern Europe and in fact everywhere, in virtually

every country (including Western Europe or U.S ). People circumvent

bureaucracy and inconvenient public policy by taking the issue into

their own hands to create their own housing. Much of this construction

is of good quality, acceptable as to sanitation and safety requirements.

It is also unrecorded in the local cadaster and is off the property tax

rolls, cannot be mortgaged and carries the threat of public prosecution.

The UN and the EU, as well as other organizations continue to study the

problem; solutions include everything from demolishment of substandard

or environmentally inappropriate construction to penalties and fees for

final recognition and legalization. The Greek proposal is an example of

this latter approach - except that what is offered to the homeowner, at

significant cost, is protection for only a limited period. Telling a

family that their home is safe for now, but may be reconsidered for

demolishment 30 years hence - or for a new round of fees - is clear

extortion-by-government.”

3. ESTIMATION OF THE DEAD CAPITAL

In 2009, inspired by Hernando de Soto’s theory (de Soto, 2000) the

authors of this paper have initiated a research at the National

Technical University of Athens in order to estimate the “dead capital”

which is locked in the informal constructions in the non planned areas

in Greece, in an effort to emphasize the need for an inclusive

legalization project. The methodology followed includes a case study in

an area with informal development, on site inspections and field work,

interviews with local experts, professionals and local authorities and

office work.

A case study area named Ag. Marina - Mikrolimano, in the municipality

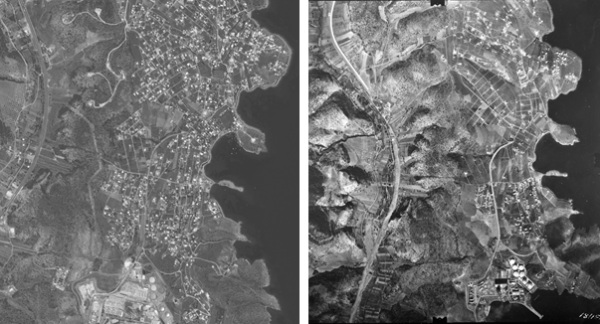

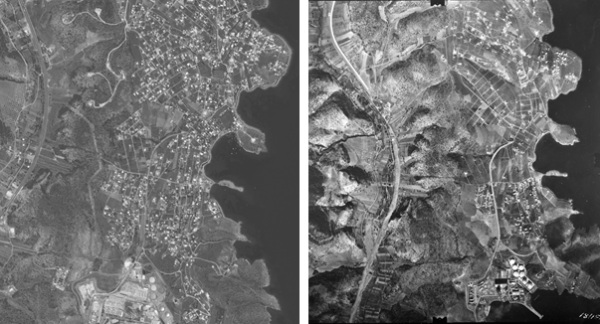

of Keratea was selected (Figure 3 left and Figure 4). The area of

interest is a typical informally developed area without detailed plans.

All parcels are legally owned but due to their small size it is not

possible to obtain building permit. However, also due to their small

size it s not possible to be used for farming. However, subdivision of

rural land was permitted in the past. As this area is close to the

capital city and by the seaside, in the General Urban Plan it is planned

to be a vacation area appropriate for second –vacation residences. As

the planning process is too slow the only pragmatic solution for land

owners is the informal housing. The total area size of this community is

170 ha and the registered permanent population is 142 inhabitants;

however in the summer time the population is up to 2000 inhabitants. The

area is mainly used for vacation purposes but gradually it becomes a

permanent-residence area. The majority of the buildings are informal

constructions.

Figure 4. Satellite image (WorldView 1) of the case study area of

2009 (left) and aerial photo of 1980 (right)

The area is still non-planned; however the municipality in 2006 has

managed to finish the necessary cadastral map in order to proceed with

the compilation of a detailed city plan.

The majority of informal settlements in Greece are similar

constructions with similar problems, in sub-urban and coastal areas

without detailed plans. Some of them are in areas where a General Urban

Plan is already ratified, some others not. If the General Urban Plan is

missing then this has to be finished first and the detailed plan

follows. This procedure may last more than 30 years.

The case of Keratea is a good sample area for this kind of research

and results derived from this research can be easily applied to the rest

of the cases. Unfortunately there are no general maps showing the areas

that are already covered by General Urban Plans and detailed city plans

in Greece. Some of the plans are in analog form, some other in digital

form all scattered in the various municipalities. Currently the

responsible Ministry is making an effort to collect all these plans and

overlap those with the recently compiled forest maps; this is a very

cumbersome task. It is roughly estimated that over 1,000,000 informal

constructions all over Greece belong to this category.

The local authority has provided the digital cadastral map in CAD

format (Figure 5 left) to facilitate this research. Additional data used

are airphotos of the area of 1980, a recent orthophoto derived from

KTIMATOLOGIO SA and a satellite image of 2009. The cadastral map was

edited in a GIS environment.

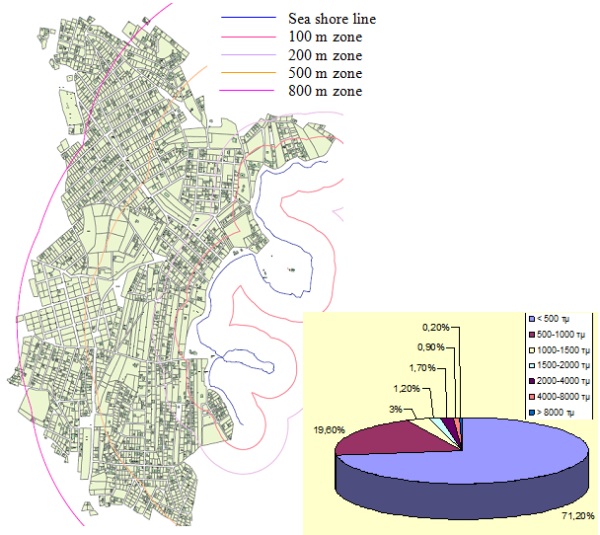

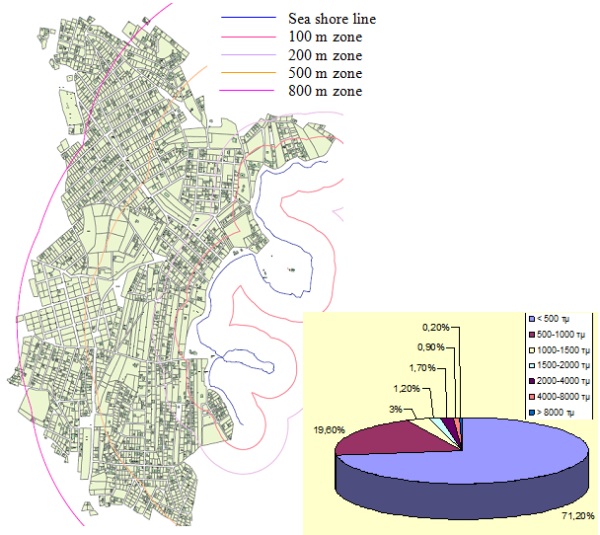

The total number of parcels in the area under study is 2,433; 62% of

them are not developed and 38% have a building. The total area size of

the parcels is 123.5 ha. Figure 5 (right) shows the percentage of

parcels according to their area size in m2. It is shown that 99% of the

parcels are less than 0.4 ha (the minimum required parcel size in order

to acquire a building permit); while 71% of the parcels are smaller than

500m2. This is a typical pattern in the greater Attika region.

The number of buildings in the study area is 1736. Of them 83.8% are

one-storey constructions, 15.6% two-storey and 0.6% three-storey. The

majority of the buildings are smaller than 200m2 (95.7%). The total

build up area size is 106,229m2.

A data base was created in order first to calculate the total

“non-taxed” tax value in the area under study. The data base was

structured according to the standardized procedure used by the tax

office for the calculation of the tax value of land in the non-planned

areas or for settlements where no specific building regulations exist.

It should be clarified here that according to existing legislation in

Greece only the developed rural parcels (those that have buildings) must

be taxed; other rural parcels are not supposed to be declared and taxed.

Figure 5. Left: Cadastral map with buffer zones according to the

distance from the sea.

Right: Distribution of buildings according to their size

3.1 Total tax value in the area under study

According to the tax office the tax value of land is the sum of the

following three parts:

a) the Basic Land Value (BLV), which is determined by

multiplying the area size of the parcel by the initial basic value

(IBV), and by the land-use coefficient. The initial basic value is the

tax value per m2 determined by the tax office, which depends on the

location, distance from the sea (with a scalable value) and access to a

specific national or regional road. The land-use coefficient depends on

the land-use category, e.g., agricultural land, trees or annual

cultivations, irrigated or not; pastures; rocks; forests; mines; and

other special commercial uses. The land-use coefficient value varies

from 1.0-1.8. In the study area the IBV varies as following:

- 15.50 € for a distance up to 100m from the sea

- 13.00 € for a distance between 100m -200m

- 13.00 € for a distance between 200m-500m

- 11.00 € for a distance between 500m -800m

- 6.00 € for a distance more than 800m

Zones (buffers) of a distance of 100, 200, 500 and 800 m from the sea

shore were created (Figure 5 left). All parcels in the study area are

considered to be not irrigated (according to regulations as they are

served by a network of drinking water), agricultural land with annual

cultivation; so the land-use coefficient is 1.0.

ΒLV = Parcel Area Size m2 x IBV x land-use coefficient (1)

b) the Plot Land Value (PLV), which is determined only if the

parcel is developed and only if the area size of the building is larger

than 15m2. The PLV is calculated by multiplying the initial plot value

(IPV) (determined by the tax office and depending on the location), by

the building area size, by the use of the building coefficient (UCB)

(which varies between 0.40 (for agricultural use) and 1.20 (for

commercial use) and for houses it gets the value 1.0), and by the

specific coefficients (SC). The specific coefficients are applied on the

following specific cases: for building older than 30 years (0.50), for

rough construction made of mud-bricks and/ or roof made by plates or

other cheap material (0.50), for buildings that are not connected to

electricity (0.90) or water utilities (0.95), for buildings half-damaged

by natural hazards (0.80).

In the case study area the IPV is 150.00€; all buildings in the study

area are connected with electricity and water utilities. Buildings older

than 30 years in the study area have been located by comparing the

airphotos of 1980 with the recent ones.

PLV = IPV x Building Area Size m2 x UCB x SC (2)

c) the Value of Further Development (VFD), which is determined

only for those parcels that can be further developed according to

existing zoning and planning regulations. In the study area anyway no

development is permitted as 99% of the buildings are constructed in

parcels smaller than 0,4ha, so VFD=0.

For the estimation of the tax value of each parcel the sum of the

above values may need to be multiplied by specific coefficients in the

following cases:

- Existence of “co-ownership” rights (coefficient value 0.9). Due

to lack of relevant data for this study it was considered that

owners of all parcels had “100% ownership” (there is no co-owner).

- Access to national, regional, rural or private road. This

coefficient varies from 1.3 up to 0.9. The existing road network in

the study area is a municipal network and in such case for all

parcels that have access to this network the relevant coefficient

gets the value 1.1 (except of some specific cases that are parcels

without access to a road; in such cases the relevant co-efficient

gets the value 0.9)

- Minimum distance of the parcel from the sea smaller than 800m.

This coefficient varies from 1.8 up to 1.0.

- If the parcel is under expropriation; this coefficient is 0.5.

No parcel in the study area belongs to this category.

Vtax land = (BLV + PLV+ VFD) x Specific coefficients (3)

According to the above analysis the calculated total tax value of all

individual land parcels in the study area is calculated: Vtax land = 44

million €

This asset should theoretically be taxed but as the constructions are

illegal, undeclared and invisible until today it is not.

3.2. The real “dead capital” locked in informal developments in

the non planned areas

In the following an attempt is made to estimate the dead capital that

is locked in the study area. According to information derived from the

local real estate agents the market value of the parcels in the greater

area is approximately 100 €/m2. So, the total market value of the land

under study is 123,500,000 €.

Construction costs for the illegal constructions are higher due to

the risk undertaken by the constructor (if arrested on site he will be

imprisoned). For example while the regular costs for the concrete parts

of the constructions is 240 €/m3, informal concrete construction costs

are double (480 €/m3). The cost is doubled due to corruption. However,

this is limited only to the concrete parts of the construction and not

to all other material costs. So, the total construction cost of an

informal building is estimated to be 1.5 times higher than the regular

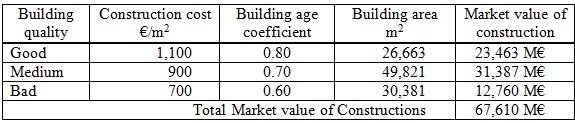

costs. Through the field work the buildings in the area have been

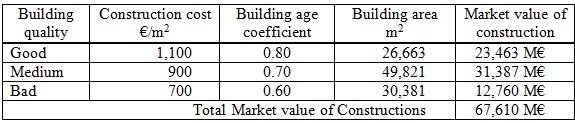

classified into three categories according to their construction

quality. The total construction cost for each category is estimated as

following:

- Good quality: 1,100 €/m2

- Medium quality: 900 €/m2

- Bad quality: 700 €/m2

A classification of all the buildings in the area of interest

according to their construction time was attempted by interpretation of

aerial photos of various years. It is noticed that a classification of

all buildings in three categories according to their age shows that

there is much overlap with the classification according to the building

quality. An explanation could be that owners of informal buildings

hesitate to invest on construction improvements due to the risk of

demolition. Few exceptions were noticed. For the purposes of this

research it was then decided to merge these two classifications into one

(Table 1). So, buildings of good quality will have age co-efficient

0.80; buildings of medium quality 0.70; and buildings of bad quality

0.60. For this study informal constructions build before 1983 are not

demolished and can be transferred so they are not included in the

estimation of the total dead capital (however according to law 4014/2011

these building must be formalized, too).

An example of the estimation of the dead capital locked in the

individual property shown in Figure 6 is given below. The parcel size is

304.3 m2 and the build up area size (2-storey building) is 183.8 m2.

Figure 6. Informal building in the study area

It is considered that the “dead” capital is the potential market

value of the real estate if legalized. This is the sum of the market

value of land (according to the available market data in the greater

area) plus the construction costs (as there is no market data

available).

| “Dead” Capital |

= Market value of land

+ Construction costs |

| where: Market value of land |

= Parcel size x Value of land/m2 |

| |

= 304.3 m2 x 100 €/m2

= 30,430 € |

| Construction costs |

= Build up area size x

Construction cost/m2 x Coefficient of age |

| |

= 183.8 m2 x 1,100

€/m2 x 0.80 (coefficient of age) = 202,180 €

|

| So: “Dead” capital

|

= 232,610 €; the

amount of money the owner has invested in the property |

| Real property tax

value |

= 49,608 €; estimated

according to the tax procedure. |

This procedure was followed in order to estimate the dead capital

locked in all individual buildings in the area under study. The estimate

of the total dead capital in the study area is given below.

On site inspections for the classification of the constructions in

the area under study have shown that:

| Good quality buildings: |

25.1% of the total number of buildings |

| Medium quality buildings: |

46.3% |

| Bad quality buildings: |

28.6% |

The total cost of construction is 67,610 million € (Table 1). The

total market value of land of the developed parcels in the study area

is: 100€/m2x (123.5 ha x 0.38) = 40 million €

The “Dead” Capital for the study area is:

“Dead” Capital = Market value of land + Construction costs = 67,61 + 40

= 107,67 million €

Table 1. Estimate of the total market value of the constructions

in the study area

For the whole Greece, a rough estimation gives:

- The estimated “Dead” Capital for approximate 1 million informal

constructions in the non planned areas is ~ 72 billion €. This asset

is not mortgaged, not taxed and cannot be transferred until today.

- If government decides an increase of the tax values in such

areas so that the tax value will be ½ of the market value, the tax

value will be 36 billion €

- With a legalization fee ~7% of tax value (proposed by the

authors) the expected revenue could be up to ~2.5 billion €. To this

sum all other loss of revenue should be added due to loss of annual

property taxes, loss of transaction fees, loss of investment for

further environmental improvements (green real estate), loss of job

positions, etc.

4. CONCLUSIONS-PROPOSALS

The municipality of Keratea and all other municipalities all over the

country that cannot afford to provide detailed plans in their

neighborhoods according to market needs have a significant economic

impact as the real estate market is blocked. Greek citizens are expected

to pay high fees for a formalization project that has an unknown future.

Moreover expected results are questionable due to the current economic

crisis. The formalization project should be accompanied with a revision

of the planning procedures and zoning regulations and construction

permitting in Greece. Legalization should be coordinated with other

major projects, too, like the cadastre and the compilation of the forest

maps. Building permit requirements need to be simplified to prevent

duplication of surveying activities.

By this research authors wish to emphasize the need for an itegrated

strategy aiming to a clear and inclusive legalization of informal

development in Greece which requires a legal reform, too. Legalization

should be permanent and affordable to all. Attention should be paid to

eliminate the broader economic impacts of informal development, to

implement a more fair property taxation, and to acquiring the public

trust.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks to the municipality of Keratea and to KTIMATOLOGIO SA

for providing access to information, to IEKEM TEE for their cooperation

and information sharing on the relevant e-training courses and the

opinions of the Greek experts on the formalization project, to the Greek

owners of informal houses for their trust during the on-site visits,

field work and interviews, to the local real estate agents for their

valuable contribution to the estimate of the dead capital, and to the

foreigners who have kindly participated to the interviews and expressed

their concerns about the project.

REFERENCES

- Augustinus, C., Potsiou, C., 2011. Informal Urban Development in

Europe. In: Proceedings of the FIG Working Week 2011, Marrakech,

Morocco,

http://www.fig.net/pub/fig2011/ppt/ts07g/ts07g_augustinus_potsiou_5192_ppt.pdf

- De Soto, H, 2000. The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism

Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else. Basic Books, 2000.

ISBN 0-465-01614-6.

- Dimopoulou, E., Zentelis, P., 2007. Informal settlements within

a spatial development framework. In: Proceedings of Joint FIG

Commission 3, UN/ECE Working Party on Land Administration and UN/ECE

Committee on Housing and Land Management Workshop, Sounio, Greece

(unpaginated CD-ROM).

- El Sioufi, M., 2010. Climate Change and Sustainable Cities:

Major Challenges Facing Cities and Urban Settlements in the Coming

Decades. In: Proceedings of the XXIV FIG International Conference

2010, Sydney, Australia,

http://www.fig.net/pub/fig2010/papers/ps03/ps03_elsioufi_4658.pdf

- Potsiou, C., 2010. Informal Urban Development in Europe.

Experiencies from Albania and Greece, Full Version, FIG, UN HABITAT,

GLTN, Technical Chamber of Greece, p.116.

- Potsiou, C., Basiouka, S., 2010. Land expropriation in Greece -

A case study for Road Networks. In: Proceedings of the Joint FIG

Commission 3 and Commission 7 Workshop, Sofia, Bulgaria.

- Potsiou, C., Dimitriadi, 2008. Tools for Legal Integration and

Regeneration of Informal Development in Greece: A Research Study in

the Municipality of Keratea. Surveying and Land Information Science

(SaLIS), vol. 68 (2), pp. 103-118.

- Potsiou, C., Dimopoulou, E., 2011. Access to Land and Legal

Rights on Land and Housing Aspects of Greek Roma. In: Proceedings of

the FIG Commission 3 Workshop 2011, Paris.

- Potsiou, C., Ioannidis, C., 2006. Informal settlements in

Greece: The mystery of missing information and the difficulty of

their integration into a legal framework. In: Proceedings of the 5th

FIG Regional Conference, Accra, Ghana,

http://www.fig.net/pub/accra/papers/ts03/ts03_04_potsiou_ioannidis.pdf

- Tsenkova, S., Potsiou, C., Badyina, A., 2009. Self-Made Cities.

United Nations Publications. ISBN 978-92-1-117005-4., p. 113.

- World Bank, 2011. Doing Business 2011 - Making a difference for

entrepreneurs. p. 267,

http://www.doingbusiness.org/~/media/FPDKM/Doing%20Business/Documents/Annual-Reports/English/DB11-FullReport.pdf

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

Chryssy POTSIOU

Dr Surveyor Engineer, Ass. Professor, School of Rural & Surveying

Engineering, National Technical University of Athens, in the field of

Cadastre and Spatial Information Management. FIG Commission 3 chair

(2007-2010). FIG Vice President (2011-2014). Elected bureau member of

the UN ECE Working Party for Land Administration (2001-2013), member of

the management board of KTIMATOLOGIO SA; elected bureau member of

HellasGIs and the Hellenic Photogrammetric and Remote Sensing Society.

Ifigenie BOULAKA

Surveying Engineer, graduated from National Technical University of

Athens in 2010, working in the private sector.

CONTACTS

Ass. Professor Dr Chryssy POTSIOU

School of Rural & Surveying Engineering, National Technical University

of Athens

9 Iroon Polytechniou St.

Athens

GREECE

Tel. +302107722688

Fax +302107722677

Email:

chryssy.potsiou@gmail.com

|