Article of the Month -

April 2008

|

Using Cadastres to Support Sustainable Development

Professor Ian WILLIAMSON, Centre for Spatial Data

Infrastructures and Land Administration, The University of Melbourne,

Australia

This article in .pdf-format (236

kB)

This article in .pdf-format (236

kB)

1) This paper was presented for the

first time at the Spanish IX National Congress of Surveying Engineers

TOP-CART 2008 in Valencia, Spain 18-21 February 2008.

ABSTRACT

An important government activity for all nation states is building

and maintaining a land administration system (LAS) with the primary

objective of supporting an efficient and effective land market. This

usually includes cadastral surveys to identify and subdivide land, land

registry systems to support simple land trading (buying, selling,

mortgaging and leasing land) and land information systems to facilitate

access to the relevant information, increasingly through an Internet

enabled e-government environment. For most countries a cadastre is at

the core of the LAS providing spatial integrity and unique land parcel

identification in support of security of tenure and effective land

trading. For many cadastral and land administration officials and for

much of society, these are the primary, and in many cases the only roles

of the cadastre and LAS. However the role, and particularly the

potential of LAS and their core cadastres, have rapidly expanded over

the last couple of decades and will continue to change in the future.

Cadastres provide the location or place for many activities in the

built environment through the cadastral map. This in turn provides the

spatial enablement of the broader land administration system. Cadastres

permit geocoding of property identifiers and particularly street

addresses that then facilitate spatially enablement government and wider

society. While the land market function of cadastres is essential, the

ability to spatially enable society is proving to be just as important

as or even more important than the land market function. In particular

spatial enablement allows governments to more easily deliver sustainable

development (economic, environmental, social and governance dimensions),

increasingly the over-arching objectives of government.

This paper describes the role that cadastres play in land

administration systems and also the provision of the spatial dimension

of the built environment in national spatial data infrastructures

(NSDI). The paper then explores how the cadastre supports spatial

enablement of government and wider society to pursue sustainable

development goals. It concludes by challenging land administration

officials to capitalize on the potential of LAS and cadastres to improve

the achievement of these goals.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This article draws on the collegiate creative efforts of colleagues

in the Centre for Spatial Data Infrastructures and Land Administration,

Department of Geomatics, University of Melbourne, Australia and

particularly joint research with Associate Professor Abbas Rajabifard

and Ms Jude Wallace. However any errors are entirely the author’s

responsibility.

1. INTRODUCTION

Land surveyors, lawyers and land administrators are experts in

designing, building and managing cadastral systems as core components of

our land administration systems (LAS). They are experienced in creating,

describing and defining land parcels and associated rights.

Historically, society required these skills to support an efficient and

effective land market in which these rights in land are traded to

promote economic development. By the mid nineteenth century, trading

involved buying, selling, mortgaging and leasing of rights in land. By

the mid twentieth century, land administration and cadastral officials,

and associated legal and surveying professionals, assumed that they

understood land markets, and that they had developed appropriate

professional skills to serve the needs of those markets.

Unfortunately these professionals were involved in supporting the

land trading activities, not designing them. Simply there is little

documentation in the literature on how to design and build a land market

or even on the development and growth of land markets (however, see

Wallace and Williamson, 2006a).

It is ironic that surveyors, for example, pride themselves on working

from the “whole to the part”, yet they gave little effort to designing

land markets, and then designing the cadastre, a LAS, and supporting

technical and administrative skills to support them. Historically, as

professionals we went the other way round: we often designed LAS and

then hoped that they would support efficient and effective land markets.

Experience around the world shows that the results in many countries are

less than satisfactory.

In general existing land administration (LA) skills are appropriate

for simple land markets which focus on traditional land development and

simple land trading; however land markets have evolved dramatically in

the last 50 years and have become very complicated, with the major

wealth creation mechanisms in the most developed countries focused on

the trading of complex commodities.

While the expansion of our LAS to support the trading of complex

commodities offers many opportunities for LA administrators, one

particular commodity - land information and particularly its spatial

dimension – has the potential to significantly change the way societies

operate, and how governments and the private sector do business.

The growth of markets in complex commodities is a logical evolution

of our people to land relationships, and our evolving cadastral and LAS.

The changing people to land relationships, the need to pursue

sustainable development and the increasing need to administer complex

commodities within an ICT (information and communications technologies)

enabled virtual world, offer new opportunities for our land

administration systems as they increasingly play a key role in spatially

enabling governments and wider society. However many challenges need to

be overcome before these opportunities can be achieved. For an overview

of trends in spatially enabling government and society see Rajabifard

(2007), PCGIAP (2007) and OSDM (2007).

Research aimed at understanding and meeting these challenges is

undertaken within the Centre for Spatial Data Infrastructures and Land

Administration, Department of Geomatics, University of Melbourne (

http://www.geom.unimelb.edu.au/research/SDI_research/ ). The over

arching focus of these projects is on spatially enabling government in

support of sustainable development. The Centre’s initiatives involve

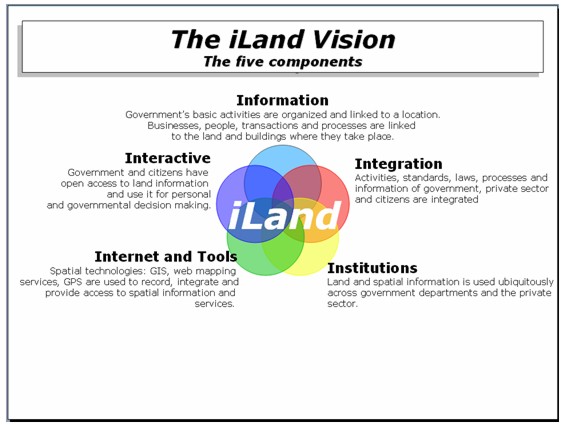

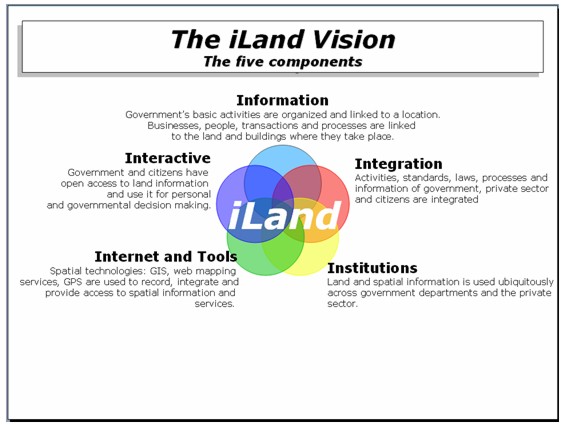

developing a new vision for managing land information called iLand.

The components of the vision include:

- a collaborative whole of government approach to managing spatial

information using spatial data infrastructure (SDI) principles,

- better understanding of the role that LAS plays in integrated

land management (land markets, land use planning, land taxation

etc),

- seamless integration of built and environmental spatial data in

order to deliver sustainable development objectives,

- improved interoperability between our land information silos

through e-land administration,

- more flexible technology and models to support cadastres,

especially to introduce a third dimension of height, and a forth

dimension of time,

- better management of the complex issues in our expanding

multi-unit developments and vertical villages,

- better management of the ever increasing restrictions and

responsibilities relating to land,

- better support for the creation and trading in complex

commodities, and

- incorporation of a marine dimension into both our cadastres and

land administration systems.

The fundamental idea is to re-engineer LAS to support emerging needs

of government, business and society to deliver more integrated and

effective information, and to use this information throughout government

and non-government processes by organizing technical systems in the

virtual environment around place or location.

2. CADASTRES AND THEIR ROLE IN LAND ADMINISTRATION SYSTEMS

An understanding of LAS and the core cadastral component, and their

evolution can help predict how they will develop.

The Importance of the Cadastre

Digital information about land is central to the policy framework of

modern land administration and sustainability accounting (Williamson,

Enemark and Wallace, 2006a). The cadastre, or the large scale, land

parcel map related to parcel indices, is the vital information layer of

an integrated land management system, and, in future, will underpin

information systems of modern governments.

While some developed countries do without a formal “cadastre”, most

generate digital parcel maps (or digital cadastral data base or DCDB)

reflecting land allocation patterns, uses and subdivision patterns, and

even addresses and photographs. A country’s DCDB is its core information

layer that reflects the use and occupation of land by society – the

built environment. Critically it provides the spatial component for LAS

and more particularly the location and place dimension with the most

useful output being a geocoded street address of each property. Simply

the cadastre is the central component in spatially enabling government.

It is destined for a much broader role as fundamental government

infrastructure equivalent to a major highway or railway, though it was

originally created on behalf of taxpayers merely for better internal

administration of taxation, and, more recently, titling of land in

support of more efficient and effective land markets. Without these

digital facilities, modern governments cannot understand the built

environment of cities, manage land competently, utilise computer

capacity to assist policy making, or retrieve significant value out of

land.

The greatest potential of the DCDB lies with the information industry

at large, as the principal means of translating geographic coordinates

and spatial descriptors of land parcels into meaningful descriptions of

places that everybody can understand. Land parcels describe the way

people physically use and think about their land. The familiar

configuration of parcel based descriptions in the DCDB ensures

people-friendly identification of precise locations of impact of private

ownership and, more vitally, of government, business and community

policies, regulations and actions. In cadastres supported by

professional surveyors, the descriptions have the added advantage of

being legally authoritative.

While having a cadastre is not mandatory for a LAS, all modern

economies recognize its importance, and either incorporate a cadastre or

its key components in their LAS. For example, Australian LAS did not

evolve from a traditional cadastral focus as did many of their European

counterparts, but their cadastres are equal to, and sometimes improve

upon, the classic European approach.

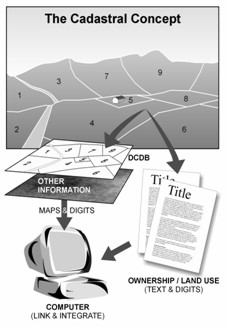

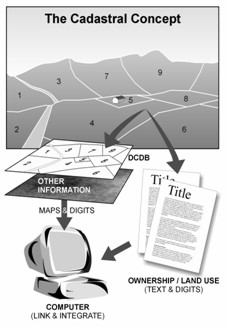

The cadastral concept shown in Figure 1 (FIG, 1995) is simple and

clearly shows the textual and spatial components, which are the focus of

land surveyors, land registry and cadastral officials. The cadastre

provides a spatial integrity and unique identification for land parcels

within LAS. However, while the cadastral concept is simple,

implementation is difficult and complex. After ten years, the model

still remains a useful depiction of a cadastre. However it needs to be

extended to incorporate the evolving and complex rights, restrictions

and responsibilities operating in a modern society concerned with

delivering sustainable development as well as the social context of

people to land relationships. It also does not show the important roles

for the cadastre in supporting integrated land management, or in

providing critically important land information to enable the creation

of a virtual environment, and, at a more practical level, e-government.

However, other initiatives of the International Federation of Surveyors

(FIG) do highlight the changing roles of the cadastre, such as CADASTRE

2014 (FIG, 1998) and the UN-FIG Bathurst Declaration on Land

Administration for Sustainable Development (FIG, 1999).

Figure 1. The Cadastral Concept. (FIG, 1995)

The Evolution of Land Administration Systems

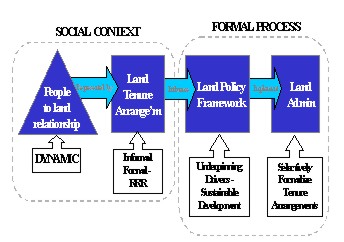

The evolution of LAS is influenced by the changing people to land

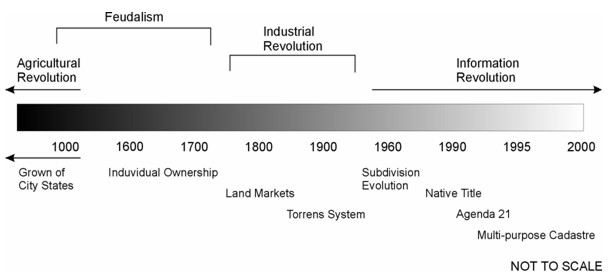

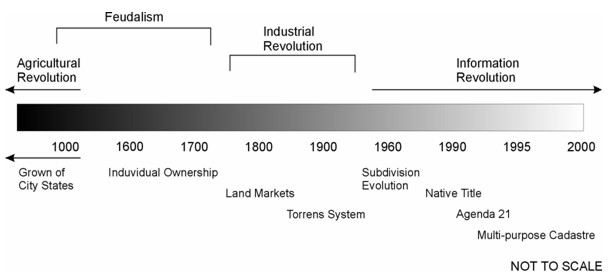

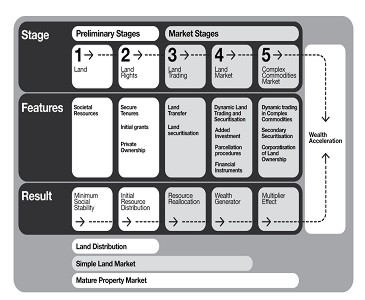

relationships over the centuries. Even though Figure 2 depicts a Western

example of this evolving relationship, a similar evolution can be

plotted for most societies. This diagram highlights the evolution from

feudal tenures, to individual ownership, the growth of land markets

driven by the Industrial Revolution, the impact of a greater

consciousness about managing land with land use planning being a key

outcome, and, in recent times, the environmental dimension and the

social dimension in land (Ting and others, 1999). Historically, an

economic paradigm drove land markets; however this has now been

significantly tempered by environmental and more recently social

paradigms. Simply, the people to land relationships in any society are

not stable, but are continually evolving.

Figure 2. Evolution of people to land

relationship. (Ting and others, 1999)

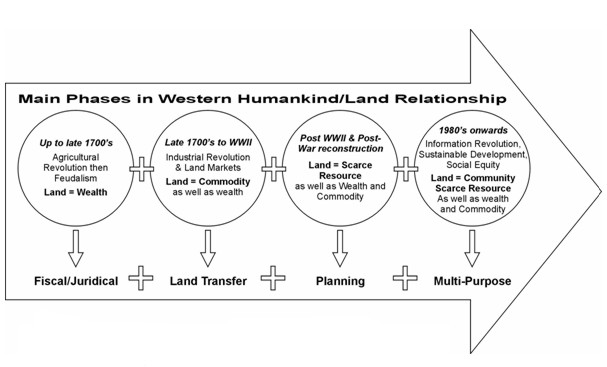

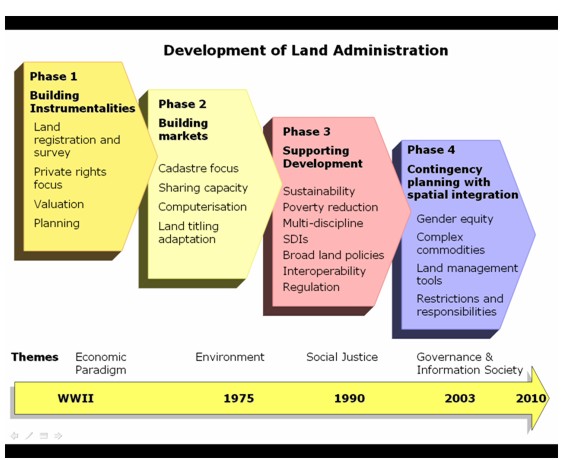

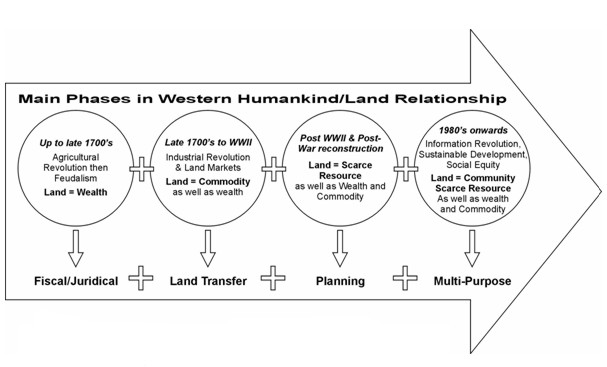

In turn most civilisations developed a land administration or

cadastral response to these evolving people to land relationships.

Figure 3 depicts the evolution of these responses over the last 300

years or so in a Western context. The original focus on land taxation

expanded to support land markets, then land use planning, and, over the

last decade or so, to provide a multi-purpose role supporting

sustainable development objectives (Ting and Williamson, 1999).

Figure 3. The Land Administration Response.

(Ting and Williamson, 1999)

Even within this evolution, current LAS must continue to service the

19th century economic paradigm by defining simple land commodities and

supporting simple trading patterns (buying, selling, leasing and

mortgaging), particularly by providing a remarkably secure parcel

titling system, an easy and relatively cheap land transfer system, and

reliable parcel definition through attainable surveying standards.

Arguably, Australia was a world leader in adapting its LASs to

support land parcel marketing. Major innovations of the Torrens system

of land registration and strata titles are copied in many other

countries. However, because of the pace of change, the capacity of LAS

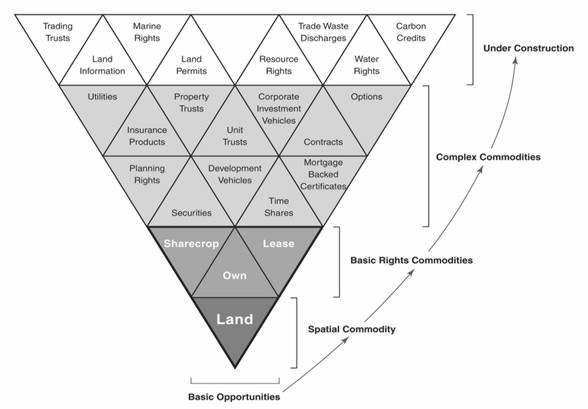

to meet market needs has diminished. The land market of say 1940, is

unrecognisable in today’s modern market. After WW II, new trading

opportunities and new products were invented. Vertical villages, time

shares, mortgage backed certificates used in the secondary mortgage

market, insurance based products (including deposit bonds), land

information, property and unit trusts, and many more commodities, now

offer investment and participation opportunities to millions, either

directly or through investment or superannuation schemes. The controls

and restrictions over land have become multi-purpose, and aim at

ensuring safety standards, durable building structures, adequate service

provision, business standards, social and land use planning, and

sustainable development. The replication of land related systems in

resource and water contexts is demanding new flexibilities in our

approaches to land administration (Wallace and Williamson, 2006a).

In Australia the combination of new management styles,

computerization of activities, creation of data bases containing a

wealth of land information, and improved interoperability of valuation,

planning, address, spatial and registration information allowed much

more flexibility. However, Australian LASs remain creatures of their

history of state and territory formation. They do not service national

level trading and are especially inept in servicing trading in new

commodities. Moreover, modern societies, which are responding to the

needs of sustainable development, are now required to administer a

complex system of overlapping rights, restrictions and responsibilities

relating to land – our current land administration and cadastral systems

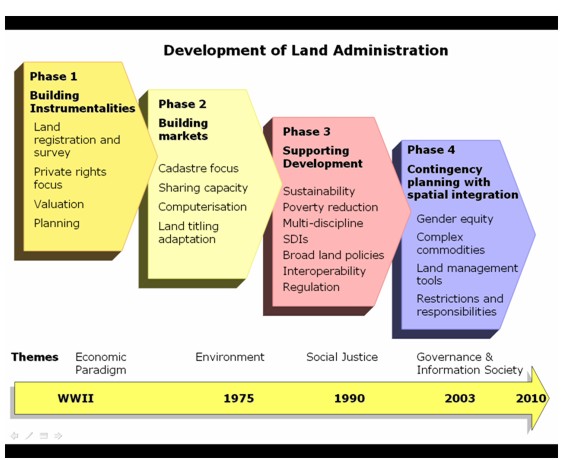

do not service this need. A diagrammatic representation of the

development of land administration (and cadastral) systems from a policy

focus is shown in Figure 4. Unfortunately many Australian LAS still do

not appreciate the central role they play in spatially enabling

government and as such are not achieving their full potential.

Figure 4. Development of Land Administration

(after Wallace and Williamson, 2005)

The Formalization of Tenures

Modern societies are also now realising that many rights,

restrictions and responsibilities relating to land exist without

formalisation by governments for various policy or political reasons.

This does not mean these rights, restrictions and responsibilities do

not exist, but that they have not been formalized in recognizable land

administration or equivalent frameworks. A good example is the

recognition of indigenous aboriginal rights in land in Australia in the

1980s. Prior to the Mabo and Wik High Court decisions and the resulting

legislation in Australia, indigenous rights did not formally exist.

Their existence was informal but strongly evidenced by song lines,

cultural norms and other indigenous systems, a situation still familiar

in the developing world where indigenous titles await more formal

construction.

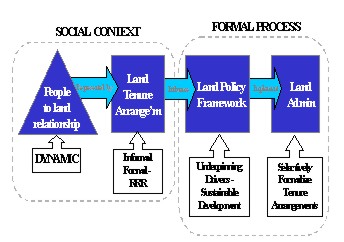

The process of formalising tenure and rights, restrictions and

responsibilities in land is depicted in Figure 5 (Dalrymple and others,

2004 and 2005; Dalrymple, 2006). An understanding of both formal and

informal rights is important as we move to develop land administration

and cadastral systems that are sensitive to sustainable development

objectives. Additionally, we need to recognize that change management

processes and adaptation of formal systems always lag behind reality:

all mature systems will simultaneously sustain both informal and highly

formalized rights because the systems are not yet ready for emerging

interests. Frequently, some rights will be deliberately held in informal

systems: one of the largest and most significant management tools in

Australia, the trust, remains beyond the land administration

infrastructure and involves utilization of paperwork generated by

lawyers and accountants and held in their filing drawers.

Figure 5. Formalisation of tenures.

(Dalrymple, Wallace and Williamson, 2004)

Other rights involve minimal formalization for different reasons.

Residential leases, too common and too short term to warrant much

administrative action, are traditionally organized outside LAS. These

land rent-based distribution systems nevertheless remain potentially

within the purview of modern LAS, policy makers and administrators, as

illustrated by Australia’s development of a geo-referenced national

address file (GNAF) produced by PSMA Australia (PSMA, 2007). Indeed the

development of spatial, as distinct from survey, information provides

the timeliest reminder that information about land is potentially one of

the most remarkable commodities in the modern land market. Certainly

this commodity of information is of core interest to LA administrators.

Implementing and Understanding Regulations and Restrictions

While many rights, restrictions and responsibilities in land have not

been formalized, many are established by statute or regulation but are

not recorded in land registries, or any other form of register. Land

uses over time must be managed to mitigate long term deleterious impacts

and support sustainable development.

As an example, Australian problems of erosion, salinity and acidity

are well documented. Over time, attempts to manage these shared impacts

by regulating tree clearance, water access, chemical use, building

standards, and more, led to very great increases in the number of laws,

regulations and standards applying to land based activities. The lack of

coherent management of restrictions and the information they generate is

now apparent.

The problem of increasing complexity of social and environmental

restrictions over land is now straining our systems, and in some cases

failing. For example, the State of Victoria, Australia now has over 600

pieces of legislation that relate to land, and the national Australian

Government has a similar amount. Most of these are administered outside

our land administration systems. This is a world wide experience. Calls

for inclusion of restrictions on land in traditionally organised LAS are

common and international.

The idea of including “all restrictions in the land register” was a

first-grab solution that is now recognized as impractical. Society needs

a more transparent and consistent approach in dealing with these

restrictions. While modern registries are adapting to manage those

restrictions compatible with their traditional functions, spatial

enablement of governments and businesses offer different solutions

(Bennett and others, 2005, 2008a and 2008b). The management of these

many rights, restrictions and responsibilities (RRR) has introduced the

concept of adding RRR either “above or below” the land register. That is

if it is “above the register”, it is included on the register with all

the government guarantees and controls that are associated with

registered interests. If it is “below the register” the RRR are not

included on the register but use the integrity of the register or

information flowing from the register such as a geocoded street address

to reference the information.

The Changing Nature of Ownership

The rapid growth of restrictions on land in modern societies is

paralleled by a change in the nature of land ownership. Nations are

building genuine partnerships between communities and land owners, so

that environmental and business controls are more mutual endeavors.

Rather than approach controls as restrictions, the nature of ownership

is redesigned to define opportunities of owners within a framework of

responsible land uses for delivery of environmental and other gains.

This stewardship concept is familiar to many Europeans long used to the

historical, social and environmental importance of land. For these

Europeans, the social responsibilities of land owners have a much longer

heritage, with the exemplar provision in the German Constitution

insisting on the land owner’s social role. The nature of land use in The

Netherlands, given much of the land mass is below sea level, presupposes

high levels of community cooperation, and integrates land ownership

responsibilities into the broader common good. The long history of rural

villages in Denmark and public support for the Danes who live in rural

areas also encourages collaboration. (Williamson and others, 2006b)

The Australian mining industry provides typical examples of

collaborative engagement of local people, aboriginal owners and the

broader public. The Australian National Water Initiative and the

National Land and Water Resources Audit reinforce the realisation that

activities of one land owner affect others. The development of market

based instruments (MBI), such as EcoTenders and BushTenders, is an

Australian attempt to build environmental consequences into land

management. Australia’s initiatives in “unbundling” of land to create

separate, tradable commodities, including water titles, are now

established and are built into existing land administration systems as

far as possible. As yet a comprehensive analysis of the impact of

unbundling land interests on property theory and comprehensive land

management is not available.

Whatever the mechanism, modern land ownership has taken on social and

environmental consequences, at odds with the idea of an absolute

property owner. Australia and European approaches to land management are

inherently different. While Europe is generally approaching land

management as a comprehensive and holistic challenge requiring strong

government information and administration systems, Australia is creating

layers of separate commodities out of land and adapting existing LAS as

much as possible to accommodate this trading without a national

approach. In these varying national contexts, the one commonality, the

need for land information to drive land management in support of

sustainable development, will remain the universal land administration

driver of the future. (Williamson and others, 2006b)

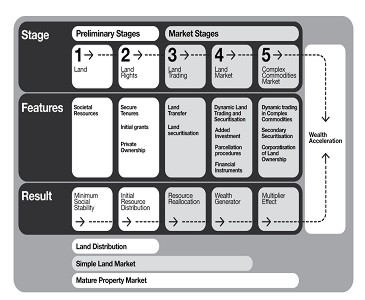

3. LAND MARKETS

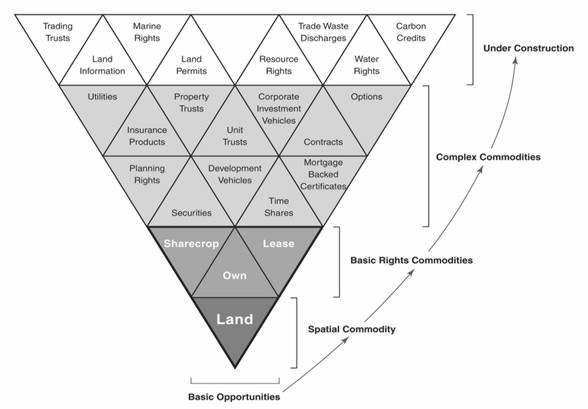

As previously stated, the land market of 1940 is unrecognisable in

today’s modern market (Figure 6). Modern land markets evolved from

systems for simple land trading to trading complex commodities. New

trading opportunities and new products were, and continue to be,

invented. The controls and restrictions over land became multi-purpose

with an increasing focus on achieving sustainable development

objectives.

Figure 6. Evolution Of Land Markets. (Wallace

and Williamson, 2006a)

As with simple commodities such as land parcels, all commodities

require quantification and precise definition (de Soto, 2000). While LAS

have not yet incorporated the administration of complex commodities to a

significant degree, these modern complex land markets offer many

opportunities for LA administrators and associated professionals, if

they are prepared to think laterally and capitalise on their traditional

measurement, legal, technical and land management skills.

This complexity is compounded by the “unbundling of rights in land”

(ie water, biota etc) thereby adding to the range of complex commodities

available for trading. For example, the replication of land related

systems in resource and water contexts is demanding new flexibilities in

our approaches to land administration (Wallace and Williamson, 2006a).

These emerging demands will stimulate different approaches to using

cadastral information.

Our understanding of the evolution of land markets is limited, but it

must be developed if LA administrators are going to maximise the

potential of trading in complex commodities by developing appropriate

land administration systems (Wallace and Williamson, 2006a). Figure 6

shows the various stages in the evolution of land markets from simple

land trading to markets in complex commodities. The growth of a complex

commodities market showing examples of complex commodities is presented

diagrammatically in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Complex commodities market. (Wallace

and Williamson, 2006a)

4. THE IMPORTANCE OF SPATIAL DATA INFRASTRUCTURES

All LAS require some form of spatial data infrastructure (SDI) to

provide the spatial integrity for rights, restrictions and

responsibilities relating to land, and the resulting land information.

However SDI is an evolving concept. In simple terms, it is as an

enabling platform linking data producers, providers and value adders to

data users. SDIs are crucial tools in facilitating use of spatial data

and spatial information systems. They allow the sharing of data, which

enables users to save resources, time and effort when acquiring new

datasets. Many nations and jurisdictions are investing in developing

these platforms and infrastructures to enable their stakeholders to

adopt compatible approaches to creation of distributed virtual systems

to support better decision-making. The success of these systems depends

on collaboration between all parties and their design to support

efficient access, retrieval and delivery of spatial information

(Williamson and others, 2003).

The steps to develop an SDI model vary, depending on a country’s

background and needs. However, it is important that countries develop

and follow a roadmap for SDI implementation. Aspects identified in the

roadmap include the development of an SDI vision, the required

improvements in national capacity, integration of different spatial

datasets, the establishment of partnerships, and the financial support

for an SDI. A vision within the SDI initiative is essential for sectors

involved within an SDI project and for the general public. The SDI

vision helps people to understand the government’s objectives and work

towards them. Unfortunately many land administrators under-estimate the

importance of SDIs in building efficient and effective LAS. They focus

on the immediate administrative needs and tasks to provide security of

tenure and the support for simple land trading, a narrow focus that

restricts the ability of LAS organizations to contribute to the whole of

government and wider society through spatial enablement.

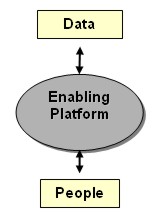

SDI as an enabling platform

Effective use of spatial information requires the optimisation of

SDIs to support spatial information system design and applications, and

subsequent business uses. Initially SDIs were implemented as a mechanism

to facilitate access and sharing of spatial data hosted in distributed

GISs. Users, however, now require precise spatial information in real

time about real world objects, and the ability to develop and implement

cross-jurisdictional and inter-agency solutions to meet priorities, such

as emergency management, natural resource management, water rights

trading, and animal, pest and disease control.

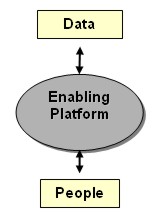

To achieve this, the concept of an SDI is moving to a new business

model, in which the SDI promotes partnerships of spatial information

organisations (public/private), allowing access to a wider scope of data

and services, of greater size and complexity than they could

individually provide. SDI as an enabling platform can be viewed as an

infrastructure linking people to data (Rajabifard and others, 2006)

through linking data users and providers on the basis of the common goal

of data sharing (Figure 8). However, there is a need to move beyond a

simple understanding of SDI, and to create a common rail gauge to

support initiatives aimed at solving cross-jurisdictional and national

issues. This SDI will be the main gateway through which to discover,

access and communicate spatially enabled data and information about the

jurisdiction.

Figure 8. SDI connecting people to data.

According to Masser et al (2007), the development of SDIs over the

last 15 years, and the vision of spatially enabled government, have many

parallels, but there are also important differences. The challenge is to

develop an effective SDI that will support the vast majority of society,

who are not spatially aware, in a transparent manner. All types of

participating organisations (including governments, industries, and

academia) can thus gain access to a wider share of the information

market. This is done by organisations providing access to their own

spatial data and services, and in return, becoming contributors, and

hence gaining access to the next generation of different and more

complex services. The vision is to facilitate the integration of

existing government spatial data initiatives for access and delivery of

data and information. This environment will be more than just the

representation of feature based structures of the world. It will also

include the administration and institutional aspects of these features,

enabling both technical and institutional aspects to be incorporated

into decision-making. Following this direction, in Australia for

example, researchers have defined an enabling platform called Virtual

Australia (Rajabifard and others, 2006). The concept and delivery of

Virtual Australia aim to enable government and other users from all

industries and information sectors to access both spatial information

(generally held by governments) and applications which utilise spatial

information (developed by the private sector and governments). The next

step in the evolution of SDIs is their role as an enabling platform in

support of a spatially enabled society (Rajabifard, 2007).

SDI and Sustainable Development

While SDIs play an essential role in supporting LAS, they also have a

wider role in supporting sustainable development objectives. Achievement

of sustainable development is not possible without a comprehensive

understanding of the changing natural environment, and monitoring the

impact of human activities by integrating both the virtual

representations of the built and natural environments. Despite the

significance of data integration however, many jurisdictions have

fragmented institutional arrangements and data custodianship in the

built and natural information areas. For example, the land

administration, cadastral or land titles office (which has a key role in

providing built environment, people relevant, data) is often separated

from state or national mapping organizations which have the

responsibility of managing the natural environment data. This

fragmentation among data custodians has brought about a diversity of

approaches in data acquisition, data models, maintenance and sharing.

Many countries are attempting to address these inconsistencies through

development of national SDIs. However, further steps of a framework and

associated tools to facilitate integration of multi-sourced data, are

also needed. (Mohammadi and others, 2006 and 2007). An SDI can provide

the institutional, administrative, and technical basis to ensure the

national consistency of content to meet user needs in the context of

sustainable development.

5. THE CONTRIBUTION OF LAND ADMINISTRATION SYSTEMS TO iLand

This brief review of the evolution of cadastres, land administration

systems, SDIs and land markets shows that the traditional concept of

cadastral parcels representing the built environmental landscape is

being replaced by a complex arrangement of over-lapping tenures

reflecting a wide range of rights, restrictions and responsibilities,

and that a new range of complex commodities, building on this trend, has

emerged. To a large extent these developments are driven by the desire

of societies to better meet sustainable development objectives. There is

no reason to believe that this trend will not continue as all societies

better appreciate the needs to manage the environment for future

generations and deliver stable tenure and equity in land distribution.

While the growth of complex commodities offers huge potential for

cadastral systems to play a greater role in delivering sustainable

development objectives and supporting the trading of these complex

commodities in particular, one complex commodity, land information, is

capable of transforming the way government and the private sector do

business. The potential offered by land information in a virtual world

in spatially enabling government is so large, it is difficult to

contemplate. We are starting to glimpse this potential in such

initiatives as Google Earth and Microsoft’s Virtual Earth, but this is

barely a start. These predictions of the importance of spatial

information are also recognized in many influential forums including in

the prestigious journal NATURE, and in the Australian Prime Minister’s

statement on frontier technologies for building and transforming

Australia’s industries (December, 2002) – both these examples place the

growth and importance of the geosciences alongside nanotechnology and

biotechnology as transformational technologies in the decade ahead.

With regard to the importance and growth in land administration and

its cadastral core as shown in Figure 4, Figure 9 (Williamson, 2006)

uses a a technology focus to show the transformation of land

administration and cadastral systems over the last three decades or so.

The figure shows five stages in the evolution of our cadastral systems

from a technology perspective. The first stage recognizes that

historically cadastral systems were manually operated with all maps and

indexes hard copy. At this stage, the cadastre focused on security of

tenure and simple land trading. The 1980s saw the computersiation of

these cadastral records with the creation of digital cadastral data

bases (DCDBs) and computerized indexes. While this computerization did

not change the role of the land registry or cadastre, it was a catalyst

felt world wide, initiating institutional change to start bringing the

traditionally separate functions of surveying and mapping, cadastre and

land registration together.

Figure 9. Technical evolution of land

administration

With the growth of the Internet, the 1990s saw governments start to

web enable their land administration systems as they became more service

oriented. As a result, access over the Internet to cadastral maps and

data was possible. This facilitated digital lodgment of cadastral data

and opened up the era of e-conveyancing. However, the focus on security

of tenure and simple land trading within separate institutional data

silos still continued. At the same time, this era also saw the

establishment of the spatial data infrastructure (SDI) concept (see

Williamson and others, 2003 and Rajabifard and others, 2005). The SDI

concept, together with web enablement, stimulated the integration of

different data sets (and particularly the natural and built

environmental data sets) with these integrated data sets now considered

critical infrastructure for any nation state.

Now a significant refinement of web enabled land administration

systems aims to achieve interoperability between disparate data sets,

facilitated by the partnership business model. This marks the start of

an era where basic land, property and cadastral information can form an

integrating technology between many different businesses in government,

such as planning, taxation, land development and local government. An

example is the new Shared Land Information Platform (SLIP) being

developed by the state Government of Western Australia (Searle and

Britton, 2005). A key catalyst for interoperability is also the

development of high integrity geocoded national street address files,

such as the Australian GNAF (Paull and Marwick, 2005 and PSMA, 2007).

Similarly, “mesh blocks”, small aggregations of land parcels, are

revolutionizing the way census and demographic data is collected,

managed and used (Toole and Blanchfield, 2005). These refinements

potentially extend to better management of the complex arrangement of

rights, restrictions and responsibilities relating to land that are

essential to achieving sustainable development objectives (Bennett and

others, 2005, 2008a and 2008b). They also stimulate re-engineering of

cadastral data models to facilitate interoperability between the

cadastre, land use planning and land taxation for example (Kalantari and

others, 2005, 2006 and 2008).

The future focus will be on realising the potential of land and

cadastral information. The use and potential of cadastral data as an

enabling technology or infrastructure will outweigh its value to

government from supporting simple land trading and security of tenure.

Cadastres will not stop at the water’s edge; they will include a marine

dimension where there is a continuum between the land and marine

environments. Without this basic infrastructure the management of the

exceptionally sensitive coastal zone is very difficult, if not

impossible (Strain et al, 2006; Wallace and Williamson, 2006b, Vaez and

others, 2007).

However this is not the end of the story – researchers,

practitioners, big business and government see the potential from

linking “location” or the “where” to most activities, polices and

strategies, just over the horizon. Companies like Google and Microsoft

are actively negotiating to gain access to the world’s large scale built

and natural environmental data bases. In Australia, they are negotiating

to get access to the national cadastral and property maps as well as to

GNAF. At the same time, new technologies are being built on top of these

enabling infrastructures such as the Spatial Smart Tag which is a joint

initiative in Australia between government, the private sector and

Microsoft (McKenzie, 2005). We are starting to realise that cadastral

and land related information will dramatically spatially enable both

government and the private sectors, and society in general. In the near

future, spatially enabled systems will underpin health delivery, all

forms of taxation, counter-terrorism, environmental management, most

business processes, elections and emergency response, for example (see

for example and Rajabifard, 2007 and OSDM, 2007).

In the future, cadastral data will be seen as information and a new

concept called iLand will become the paradigm for the next

decade. iLand is a vision of integrated, spatially enabled, land

information available on the Internet. iLand enables the “where”

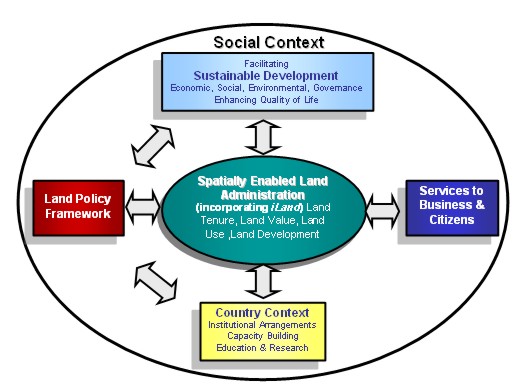

in government policies and information. The vision as shown

diagrammatically in Figure 10 is based on the engineering paradigm where

hard questions receive “design, construct, implement and manage”

solutions. In iLand all major government information systems are

spatially enabled, and the “where” or location provided by spatial

information is regarded as a common good made available to citizens and

businesses to encourage creativity, efficiency and product development.

The LAS and cadastre is even more significant in iLand. Modern

land administration demands LA infrastructure as fundamental if land

information is to be capable of supporting those “relative” information

attributes about people, interests, prices, and transactions, so vital

for land registries and taxation.

All these initiatives come together to support a new vision for

managing land information - iLand. (Williamson, Wallace and

Rajabifard, 2006)

Figure 10. The iLand Vision.

(Williamson and Wallace, 2006)

While future markets of complex commodities will continue to rely on

the underlying cadastre and land administration system, will LA

administrators embrace the definition and management of complex

commodities that do not rely on traditional cadastral boundaries and

that require merging of value, building purpose, land use and personal

owner information? How many LA administrators are capable of seeing the

international context of land information and its importance to their

national government in presentation of its investment face to the world?

Will they embrace iLand?

6. THE ROLE OF CADASTRES AND LAND ADMINISTRATION IN SPATIALLY

ENABLING GOVERNMENT

Governments can be regarded as spatially enabled when they treat

location and spatial information as common goods made available to

citizens and businesses to encourage creativity and product development.

The vision of a spatially enabled government involves establishing an

enabling infrastructure to facilitate use of place or location to

organise information about activities of people and businesses, and

about government actions, decisions and polices. Once the infrastructure

is built, spatial enablement allows government information and services,

business transactions and community activities to be linked to places or

locations. Given the potential of new technologies, use of place or

location will facilitate the evaluation and analysis of both spatial and

non-spatial relationships between people, business transactions and

government. (Williamson and Wallace, 2006; Rajabifard, 2007; OSDM, 2007;

and PCGIAP, 2007)

Most governments already have considerable infrastructure and

administrative systems for better management of land and resources.

Basic information creating processes are cadastral surveying that

identifies land; its supporting digital cadastral database (DCDB) that

provides the spatial integrity and unique land parcel identification;

registering land that supports simple land trading (buying, selling,

mortgaging and leasing land); running land information systems (LIS) for

land development, valuation and land use planning; and geographic

information systems (GIS) that provide mapping and resource information.

For modern governments at all stages of development, one question is how

best to integrate these processes, especially to offer them in an

Internet enabled eGovernment environment.

Twenty years ago, each process and collection of information, was

distinct and separate. Two changes in the world at large challenged this

silo approach. First, thanks to improvements in technology, the

infrastructure available to support modern land and resource management

now spans three distinct environments: the natural, the built and the

virtual environments. Second, the pressures on managers created by

increased populations, environmental degradation, water scarcity and

climate change, require governments to have more accurate and

comprehensive information than ever before.

How governments treat their land information will define their

transformation of internal and external processes. The eLand

administration concept as part of eGovernment initiatives is now

moving to a wider use of spatially enabled land information, expressed

in the concept of iLand - integrated, interactive spatial

information available on the Internet. The conversion of processes to

spatially enabled systems will increase useability, access and

visualisation of information.

7. THE ROLE OF THE CADASTRE IN SUPPORTING SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

These developments and drivers will introduce complexity into the

design of LAS as they adapt to assist delivery of a broader range of

public policy and economic goals, the most important of which is

sustainable development. However re-engineering land administration

systems to support sustainable development objectives is a major change

in direction for traditional LAS and is a significant challenge (Enemark

and others, 2005).

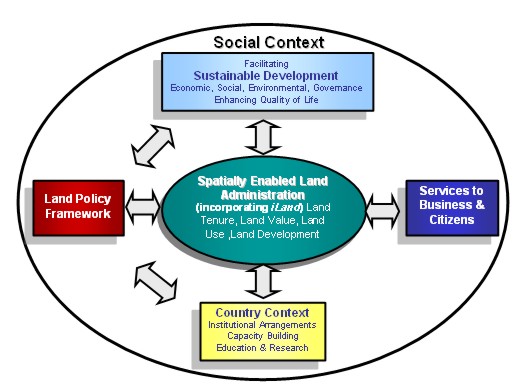

In the proceeding sections this paper has described how cadastres,

SDIs and LAS interact to spatially enable government and wider society

in pursuit of sustainable development objectives. These relationships

are shown diagrammatically in Figure 11 below. The diagram shows the

critical role that the cadastre plays in providing built environmental

data in a national SDI and how the integrated SDI can then contribute to

a LAS that supports effective land management. It is only by bringing

together the SDI and the LAS that an integrated land policy can be

implemented to support sustainable development. This integration also

provides the key role of spatial enablement of the LAS, as well as

government and wider society. Ironically only a relatively small number

of countries, the “developed countries” have the ability at the present

of achieving this objective. However the model does provide a road map

for less developed countries to move down this path.

Figure 11. The role of the cadastre in

building land administration infrastructures.

These global trends to move LAS down this path, and the national and

historical methods used to incorporate sustainable development

objectives into national LAS were examined in an Expert Group Meeting

(EGM) in Melbourne in December, 2006 with leading stakeholders and land

policy experts from Australia and Europe. (Williamson and others,

2006a). Distinctions between approaches used in modern European

democracies and in Australia were identified. The European approach

showed more integration between the standard LAS activities and measures

of sustainability. Australian policy was more fractured, partly due to

federation and the constitutional distribution of powers. In contrast,

pioneering in Australian LAS lay in incorporating market based

instruments (MBI) and complex commodities into LAS, and revitalization

of land information through inventive Web based initiatives.

Figure 12. Land management vision. (Williamson

and others, 2006b)

The EGM developed a vision for future LAS sufficiently flexible to

adapt to this changing world of new technology, novel market demands,

and sustainable development, as shown in Figure 12. This vision

incorporates and builds upon the above vision of iLand and can be

considered an infrastructure or enabling platform to support spatial

enablement of government. (Wallace and others, 2006; Williamson and

others, 2006a and 2006b). This vision is explained at a more practical

level in Figure 11 above.

8. CONCLUSION

People to land relationships are dynamic. The land administration and

cadastral responses to managing these relationships are also dynamic and

continually evolving. A central objective of the resulting land

administration systems is to serve efficient and effective land markets.

Because of sustainable development and technology drivers, modern land

markets now trade in complex commodities, however our current land

administration systems and the majority of the skills of land surveyors,

lawyers and LA administrators are focused on the more traditional

processes supporting simple land trading. The growth in complex

commodities offers many opportunities for LA administrators if they are

prepared to think laterally and more strategically.

Land information has grown in importance over the last few decades,

and is considered by many to be more important and useful to government

than in its traditional role of supporting security of tenure and simple

land trading. Land administration systems and their core cadastral

components are evolving into a new vision and essential infrastructure

called iLand that spatially enables government and provides the

“where” for all government decisions, polices and implementation

strategies. This vision requires a clear understanding and institutional

and legal structures that link the cadastre to the SDI and the wider

LAS. Without this understanding and interaction delivering the vision is

very difficult if not impossible. Ultimately, spatially enabled land

information will provide the essential link between land administration

and sustainable development.

This brief account of the future delivers a challenge to land

administration officials to design and build modern land administration

and cadastral systems capable of supporting the creation, administration

and trading of complex commodities, and particularly to use land

information to spatially enable government and society in general.

Unfortunately, unless land administration systems are refocused on

delivering transparent and vital land information and enabling

platforms, modern economies will have difficulty meeting sustainable

development objectives and achieving their economic potential.

REFERENCES

NOTE: Most referenced articles that have been authored or co-authored

by the author (Ian Williamson) are available at

http://www.geom.unimelb.edu.au/people/ipw.html

Bennett, R., Wallace, J. and Williamson, I.P. 2005. Integrated land

administration in Australia. Proceedings of the Spatial Sciences

Institute Biennial Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 12-16 September,

2005. CD ROM.

Bennett, R., Wallace J. and Williamson, I.P.2008a, Organising

property information for sustainable land administration. Journal of

Land Use Policy, Vol. 25, No. 1, 126-138.

Bennett, R., Wallace, J. and I. P. Williamson 2008b. A toolbox for

mapping and managing new interests over land. The Survey Review, 40, 307

pp.43-53 (January 2008)

Dalrymple, K, Wallace, J. and Williamson, I.P., 2004. Innovations in

Land Policy and Rural Tenures. 3rd FIG Regional Conference, Jakarata,

Indonesia, October 4-7.

http://www.fig.net/pub/jakarta/papers/ts_10/ts_10_1_dalrymple_etal.pdf

Dalrymple, K, Wallace, J. and Williamson, I.P. 2005. Transferring our

knowledge and systems – tenure formalisation. Proceedings of the Spatial

Sciences Institute Biennial Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 12-16

September, 2005. CD ROM.

Dalrymple, K. 2006. Expanding rural land tenures to alleviate

poverty. PhD thesis. University of Melbourne. See

http://www.geom.unimelb.edu.au/research/SDI_research/publications/Dalrymple%20PhD%20Thesis.pdf

Accessed 15 December, 2007.

De Soto, Hernando, 2000, The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism

Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else, Bantam Press, London,

235 pp

Enemark, S, Williamson, I.P and J. Wallace, 2005, Building modern

land administration systems in developed economies, Spatial Science

Journal, 2/50, 51-68

FIG, 1995. The FIG Statement on the Cadastre. International

Federation of Surveyors, FIG Publication No 11.

http://www.fig7.org.uk/publications/cadastre/statement_on_cadastre.html

FIG, 1998. CADASTRE 2014. International Federation of Surveyors. (http://www.fig.net/commission7/reports/cad2014/)

FIG, 1999. Bathurst Declaration on Land Administration for

Sustainable Development. International Federation of Surveyors (http://www.fig.net/pub/figpub/pub21/figpub21.htm)

Kalantari, M., Rajabifard, A., Wallace, J. and Williamson, I.P. 2005.

Towards e-land Administration – Australian on-line land information

services. Proceedings of the Spatial Sciences Institute Biennial

Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 12-16 September, 2005. CD ROM.

Kalantari, M., Rajabifard, A., Wallace, J. and Williamson, I.P. 2006.

A new vision on cadastral data models. FIG Congress Proceedings, Munich,

Germany, 8-13 October, 2006. See

http://www.fig.net/pub/fig2006/index.htm Accessed 14 December, 2007.

Kalantari, M. , Rajabifard, A., Wallace, J. & Williamson, I., 2008.

Spatially Referenced Legal Property Objects, Journal of Land Use Policy

(in press). See

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2007.04.004. Accessed 14

December, 2007.

Masser, I., Rajabifard, A., Binns, A., and Williamson, I. 2007,

Spatially Enabling Governments through SDI implementation, International

Journal of Geographical Information Science Vol. 21, July, 1-16.

Mohammadi, H., Rajabifard, A., Binns, A. and Williamson, I.P. 2006,

Bridging SDI Design Gaps with Facilitating Multi-source Data

Integration, Coordinates, Vol II, Issue 5, May 2006.

Mohammadi, H., Rajabifard, A., Binns, A. and Williamson, I.P. 2007,

Spatial Data Integration Challenges: Australian Case Studies,

Proceedings of SSC 2007, The national biennial Conference of the Spatial

Sciences Institute, 14-18 May, Hobart, Australia.

McKenzie, D. 2005. Victorian Spatial Smart Tag – How to bring spatial

information to government’s non technical users. Proceedings of the

Spatial Sciences Institute Biennial Conference, Melbourne, Australia,

12-16 September, 2005. CD ROM.

OSDM, 2007. Spatially Enabling Government. Office of Spatial Data

Management (OSDM), Australian Government.

http://www.osdm.gov.au/seg/

Accessed 14 December, 2007.

PSMA, 2007. GNAF. PSMA Australia,

http://www.psma.com.au/ Accessed 14 December, 2007

PCGIAP, 2007. Working Group 3 (Spatially Enabling Government).

Permanent Committee for GIS Infrastructure for Asia and the Pacific

(PCGIAP). See

http://219.238.166.217/pcgiap/98wg/wg3_index.htm Accessed 14

December, 2007.

Paull, D. and Marwick, B. 2005. Maintaining Australia’s Geocoded

National Address File (GNAF). Proceedings of the Spatial Sciences

Institute Biennial Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 12-16 September,

2005. CD ROM.

Rajabifard, A., Binns, A. and Williamson, I. 2005, Development of a

Virtual Australia Utilising an SDI Enabled Platform, Global Spatial Data

Infrastructure 8 and FIG Working Week Conference, 14-18 April, Cairo

Egypt.

Rajabifard, A., Binns, A. and Williamson, I. 2006, Virtual Australia

– an enabling platform to improve opportunities in the spatial

information industry, Journal of Spatial Science, Special Edition, Vol.

51, No. 1.

Rajabifard, A. (Editor) 2007, Towards a spatially enabled society.

Department of Geomatics, University of Melbourne, Australia, 399 pages.

(also see

http://www.ianwilliamson.net/SEG_flash.htm Accessed 14 December,

2007)

Searle, G. and Britton, DM. 2005. Government working together through

a shared land information platform (SLIP). Proceedings of the Spatial

Sciences Institute Biennial Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 12-16

September, 2005. CD ROM.

Strain, L., Rajabifard, A. and Williamson, I.P. 2006. Marine

Administration and Spatial Data Infrastructures. Marine Policy. 30

(2006):431-441.

Ting, L., Williamson, I.P. Grant, D. and Parker, J. 1999.

Understanding the Evolution of Land Administration Systems in Some

Common Law Countries. The Survey Review Vol. 35, No. 272, 83-102.

Ting, L. and Williamson, I.P. 1999. Cadastral trends: A synthesis.

The Australian Surveyor Vol. 4, No. 1, 46-54.

Toole, M and Blanchfield, F. 2005. Mesh blocks – from theory to

practice. Proceedings of the Spatial Sciences Institute Biennial

Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 12-16 September, 2005. CD ROM.

Vaez, S., Rajabifard, A., Binns, A. & Williamson, I. (2007), Seamless

SDI Model to Facilitate Spatially Enabled Land Sea Interface,

Proceedings of SSC 2007 ,The national biennial Conference of the Spatial

Sciences Institute, May, Hobart, Australia. See

http://www.geom.unimelb.edu.au/research/SDI_research/publications/ianpubli.htm

Accessed 15 December, 2007.

Wallace, J. and Williamson, I.P. 2005. A vision for spatially

informed land administration in Australia. Proceedings of the Spatial

Sciences Institute Biennial Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 12-16

September, 2005. CD ROM.

Wallace, J. and I.P. Williamson, 2006a. “Building Land Markets”,

Journal of Land Use Policy, Vol 23/2 pp 123-135

Wallace, J. and Williamson, I.P. 2006b. Registration of Marine

Interests in Asia-Pacific Region. Marine Policy. 30(3):207-219.

Wallace, J., Williamson, I.P. and S. Enemark, 2006. “Building a

national vision for spatially enabled land administration in Australia”,

In Sustainability and Land Administration Systems, Department of

Geomatics, Melbourne, 237-250.

Williamson, I.P. 2006. A Land Administration Vision. In

Sustainability and Land Administration Systems, Department of Geomatics,

Melbourne, 3-16.

Williamson, I.P., Rajabifard, A. and Feeney, M-E.F. (Editors). 2003.

Developing Spatial Data Infrastructures – From concept to reality.

Taylor and Francis. 316p.

Williamson, I.P., Enemark, S. and J.Wallace (eds), 2006a.

Sustainability and Land Administration Systems, Department of Geomatics,

Melbourne, 271p.

Williamson, I.P., Enemark, S. and J. Wallace, 2006b, “Incorporating

sustainable development objectives into land administration”,

Proceedings of the XXIII FIG Congress, Shaping the Change, TS 22.

Munich, Germany, October 8-13, 2006.

Williamson, I.P. and J. Wallace, 2006, “Spatially enabling

governments: A new direction for land administration systems”,

Proceedings of the XXIII FIG Congress, Shaping the Change, TS 23.

Munich, Germany, October 8-13, 2006.

Williamson, I.P., Wallace, J. and A. Rajabifard, 2006. Spatially

enabling governments: A new vision for spatial information. 17th

UNRCC-AP Conference and 12th Meeting of the PCGIAP, Bangkok, Thailand.

18-22 September 2006.

Williamson, I.P., Rajabifard, A. and J. Wallace, 2007. Spatially

enabling government – an international challenge. International Workshop

on “Spatial Enablement of Government and NSDI – Policy Implications.

Permanent Committee for GIS Infrastructure for Asia and the Pacific,

Seoul, Korea, 12 June 2007.

CONTACTS

Professor Ian Williamson

Professor of Surveying and Land Information

Department of Geomatics

Centre for Spatial Data Infrastructures and Land Administration

The University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria, Australia 3010

Email: ianpw@unimelb.edu.au

http://www.geom.unimelb.edu.au/people/ipw.html

|